By Ira Kantor

Photos Courtesy of Chapin Productions LLC

The life of Harry Chapin, charismatic musician and iconic humanitarian, was unexpectedly and tragically taken on July 16, 1981. He was 38 years old.

A human dynamo whose sheer tenacity landed him on the Billboard charts, on Broadway, in the White House, and at the forefront of the world hunger movement, Chapin lived by the mantra of “When in doubt, do something.” In following this mentality, Chapin’s 10-year solo career encompassed more than 2,000 concerts, nine studio albums, the creation of global nonprofit World Hunger Year (now WhyHunger) and the love and respect of fans, fellow musicians and key political influencers alike.

Hailed as a consummate musical storyteller, Chapin is best known for his character-driven tunes —“Taxi,” “Sniper,” “W-O-L-D,” “A Better Place to Be,” “30,000 Pounds of Bananas” and “Cat’s in the Cradle” included. Yet despite having only four Top 40 hits to his name, Chapin’s songs remain one of a kind — elevating him to the same artistic status as classic singer-songwriters of the era like James Taylor, Jim Croce, Gordon Lightfoot and John Denver.

Nearly 40 years after his death, the following 10-part oral history seeks to tell Harry Chapin’s story through the firsthand, on-the-record testimonies of the “characters” who knew him best — more than 50 family members, friends, business and political associates and musical contemporaries. For added context, Harry’s own voice, along with other relevant news articles and reviews during his lifetime, are included in italics.

While there are other individuals and events crucial to Harry’s tale who were unable to be interviewed or showcased for this series, this still seeks to provide a well-rounded retrospective of a man whose life, being, sense of accomplishment and legacy remain unsurpassed to this day.

***

Chapter IV

CAT’S IN THE CRADLE

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): Songs, albums, concerts and benefits followed in ’73 and ’74. By then my son Josh was born, Sandy wrote the lyrics for “Cat’s in the Cradle” and in December 1974 it became the number one record in the country.

Ingrid Croce (Wife of Musician Jim Croce): I’ve had a few fans write to tell me “Cat’s in the Cradle” was one of their favorite Jim Croce songs. I personally like it myself. It reminds me a bit of Cat Stevens too — his “Father and Son” song. It reflects a stage in life when young people want to separate from their folks and become their own person. It’s a tough time and they both wrote about it in a very poignant way, from different points of view. I think Harry’s music, Cat Stevens and Jim’s really capture the human condition. They are all great storytellers.

Stanley Snadowsky (Co-owner of The Bottom Line): If you listen to the song “Cat’s in the Cradle,” it’s a story of almost any young man trying to better himself. He has to sacrifice something. What you sacrifice is your family. It’s unfortunate. You don’t mean to do it. And when you establish yourself you find your son is just like (you). It’s a splice of life.

Josh Chapin (Son): It was a message to (Harry) but she wrote it as a poem about her first husband’s relationship with his father. My dad saw it and it obviously helps him to resonate with the audience if he says it’s about him, and he said it about me. It’s not, but obviously there’s something about him singing it that makes it real.

Sandy Chapin (Wife): I remember when I showed him “Cat’s in the Cradle.” He sort of dismissed it…Then when it came up again after Josh was born, he latched onto it and then sat right down and put music to it. It was kind of interesting that [he] saw it in a whole different light.

Writing that song came from a few different things. When I was driving I liked to listen to country music because the stories would keep me awake. I remember a country song I heard — it was [about] an old couple kind of having breakfast and looking out the kitchen window and there’s the old rusty play gym in the yard and they are reminiscing about how fast the time went by and all they have are the memories. So that was kind of the thought that went into the back of my head.

When Harry first started playing “Cat’s in the Cradle,” he would introduce it as, ‘This song came from a poem my wife wrote when I wasn’t home when Josh was born’ — something to that effect. I always thought that was amusing because we always learn life’s lessons too late. You don’t know lessons about parenting when your first child is born or whatever. I’d learned the lesson when I first came to New York with my first husband and moved into his parents’ apartment in Park Slope. I’m going out to teach every day. My husband is going to work as a lawyer. We’re all home at dinner time and his father has come home from work and he’s trying to talk to his son — he called him Jimmy — and he said, ‘You know, I’d like you to come down to the club’ — being the local Democratic club — ‘Come down to the club on Tuesday,’ and he’s trying to engage him in his life. He wants to organize a career in politics for his son. He’s very proud that his son had a law degree because he himself never went past the fifth grade. So he sees all this promise and possibility. He’d like to see his son be a judge someday; that to him is the highest level of accomplishment.

Anyway, there’s no response. Nothing. No dialogue, no conversation, nothing at all. So he started talking to me. He’d say to me, ‘Will you tell Jimmy that’ — this is while his son is right there in the room a few feet away — ‘Would you tell Jimmy I’d like him to come down to the club on Tuesday,’ and would start making appointments and dates through me sitting in the same room. So it occurred to me that they had no relationship. That if you don’t form a relationship at 2 you’re not going to be able to form one at whatever this was, 28, and they really didn’t.

The song has had a tremendous impact. It’s been used over and over again in Sunday sermons and a lot on Father’s Day and books and articles — references in films and TV. The whole song is about paying attention.

I didn’t have an intention of teaching a lesson. I was just telling a story because it was a story I saw that I felt very strongly about. I taught my kids folk songs. I was familiar with that kind of parable or whatever and so it was just a story about what happens if you don’t pay attention. But how could it be directed at Harry? As I say, the stories are learned after the fact. You couldn’t direct it at Harry when he has his first child because he hasn’t been there yet.

The song was written two years before Josh was born. It was written, as I say, at the time when he first went on the road. He’d come home; I was writing papers for my graduate program, I’d show him my papers. He’d put corrections on them and it was one of a number of things that I was writing along with when I was doing the “Make a Wish” stuff, and it just happened to strike a chord after Josh was born. But it had already been there. It wasn’t any comment on his parenting because it was before that. He may have directed it to himself but I didn’t.

Thomas Downey (Friend, Former Politician): I met Harry through my friend Allard Lowenstein, who was a former member of Congress and an anti-war activist. I was running for Congress in 1974. I want to say it was in the early summer of ’74 that I went over to his house. He had a house in Huntington, not far from the water. Knocked on the door. It was about 8:30 in the morning on a Saturday. Harry answered the door in his underwear and said, ‘Oh yeah, yeah, go sit on the porch.’ It was a beautiful day. So we were sitting there and he comes out with his guitar and he said, ‘I want your reaction to this song.’ So he plays for me “Cat’s in the Cradle” and I sat and listened to it. I genuinely loved it. I said, ‘That is a tremendous song. That’s going to be a gigantic hit.’ He said, ‘Do you really think so?’ I said, ‘I do.’ That’s how I met him.

Jason Chapin (Son): The fact that he was entered into the Grammy Hall of Fame for “Cat’s in the Cradle,” the fact that he’s still recognized for some of the things that he’s done so many years after he died, it’s really amazing.

***

THE NIGHT THAT MADE AMERICA FAMOUS

Ron Palmer (First Guitarist): “Cat’s in the Cradle” was number one two weeks in a row and the week after that I was gone. It was all because of the musical that Harry wanted to do.

Big John Wallace (Bassist): (Ron) was very upset about the Broadway show. “Cat’s in the Cradle” had just gotten to number one. I think it was November of ’74, and our price jumped from $2,500 a night, or whatever, to $7,500 a night and all these gigs started coming in. But Harry had this kind of bug up his ass to do Broadway. Right at the peak, he shuts everything down and goes to Broadway.

Sandy Chapin: Edgar Lansbury and Joe Beruh, I think, were the two guys who approached (Harry). This was when he was at his pinnacle of fame on top of “Cat’s in the Cradle.” They wanted to do a Broadway musical and they went ahead with the planning and so forth. Harry was to be in it. They had to look for a director. They had to raise money. Harry did fundraisers out in the Hamptons and so forth and so on.

Somehow I think he really got led into the wrong direction for his music. He was really prodded into it and it was a very, very busy time in his career too. He was working hard at building the Performing Arts Foundation and World Hunger Year and doing concerts in Europe, and somehow managed to do that too.

Alexandra Borrie (The Night That Made America Famous Cast Member): Like all shows, there were good and bad points. The show was sort of ill-conceived in that it really was a concert. The idea was that it be his songs and because he did story songs, somebody thought that they would probably translate onto stage with movement and some choreography and a little bit of more of a narrative than you get at a concert. So that’s really all it was. There was no plot. There was no narrative. There were characters that lived within the songs, but not played out on stage with any kind of dialogue.

Mercedes Ellington (The Night That Made America Famous Cast Member): It was quite an experience because it was one of the first times that two different types of music entities came together. I mean Broadway at that time usually had a kind of strict format as being something from books or whatever. The era of the jukebox musical hadn’t appeared. This was an incredible marriage of Broadway discipline combined with this kind of folk-rock singer and having his band actually on stage.

Alexandra Borrie: Harry is the soul of them. They were his songs and he delivered them the way they should be delivered. I didn’t find it difficult at all, what we were doing. You know, I’ve done many Broadway shows and I was trained and all singers were trained. It wasn’t as if we were doing complicated harmonic work necessarily. It’s hard for me to remember exactly what the musicality did entail, but it certainly wasn’t terribly difficult.

Jason Chapin: It was very innovative. I remember that it was a musical and they played all of his songs but they also were using live video. They had a guy on stage who was shooting the performers while they are performing and then it was put on a screen. I remember it was a typical Broadway set but they were trying to use a lot of technology. I think my father was trying to use a lot of his filmmaking skills to make it visually memorable.

Mercedes Ellington: There was a lot of grit in Harry’s presentations and we were encouraged to be very real about situations because they addressed real life situations. It wasn’t like this was fiction. Harry wrote about real things.

Big John Wallace: I remember one night. They were all looking down almost like a scene out of “The Producers,” you know, with like absolutely blank faces (laughs). I don’t think they were sure what they were looking at.

Jason Chapin: It was only three weeks later, I think, that they closed the place, so it was kind of not a very long memory. It definitely had mixed reviews and limited success.

I also remember that there was a little bit of a struggle going on because my father had committed to doing it and it was very important to him. I think his band members were very annoyed with him because they wanted him to go back out on the road because “Cat’s in the Cradle” had just become number one. Everyone was thinking this is when your music career can really take off and not a time to start another career.

From “Harry Chapin Brings Songs to Stage,” The New York Times, 1975: The people who put Mr. Chapin’s disks in the top 10 are probably the ones who will most enjoy the show, which is more like an animated record album than a musical. But animated it certainly is. The show’s pretentiousness tries very hard to be unpretentious, and it will probably be best liked by present devotees of Mr. Chapin, by people who like a nice sentimental little story and people impressed by flossy-colored lights. With luck there may well be enough of them.

Tom Chapin (Brother): The Broadway show sucked really. It was all in the wrong hands. All the decisions that were made were wrong. It still was a fascinating time, but it really was bad. It didn’t set up anybody in the best light in the material at all. So yeah, it was a mistake, but Harry’s credo and the way he lived his life was “When in doubt, do something.” I remember him in talks saying there’s nothing so boring as being a rock star. So let’s do Broadway. He had this thing: ‘I want to win the Nobel Peace Prize and I want to win a Grammy. I want to do it all.’ He was a glutton in the best sense of the word. A glutton for life.

What happened was Harry more and more after the reviews came out would do a third act, which was the concert and so people would go away really happy because he’d stay there.

Fred Kewley (First Manager): Harry had made a decision to stop doing the road so much and to do a Broadway show so he could make music, be on a stage, and then get home every night to Long Island rather than flying all over the country. That decision was being made as “Cat’s in the Cradle” was climbing the charts, as I recall. He and I had some pretty heavy-duty conversations about it. That thing was out there and climbing the charts and obviously good things are going to be even getting better. That’s when he decided to do this Broadway show, which I fought as much as I could fight. Broadway is a big deal to a very small crowd and for him to do that was a shame when he had a number one song about to be climbing. The sales were going through the roof and the record company’s telling me this thing is huge. It’s a real thrilling time but right when he could have capitalized on it and increased his money from $10,000 a night to $20,000, $30,000, $40,000, to do a Broadway show made no sense at all in terms of a career move.

But it was a personal move. It was something he felt he had to do to keep his wife and his family happy. He had to stop all the running he was doing in the previous years, and so he did the Broadway show. It lasted six or seven weeks.

Parts of it were very good. It was a good way to see a Harry Chapin concert. It really wasn’t a Broadway show for that blue-haired crowd. When it ended, we were able to go out there and do some big outdoor venues with 30,000 people. Those were good times but it could have been a lot better if we had had the time to really cash in on “Cats in the Cradle” in every respect, in terms of building a career and building a presence.

Big John Wallace: I think a little bit of that wave had passed by and it did cost him in the long run. But it was something he definitely wanted to do.

***

ON THE ROAD TO KINGDOM COME

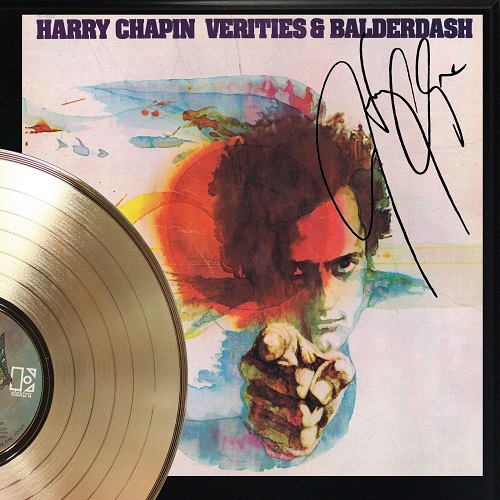

Ron Palmer: They made the decision to bring in hired guns. I think I only played on two tracks on the whole [Verities and Balderdash] album — one of them was “Cat’s in the Cradle,” I did the high harmonic parts on that, and the other one was “Six String Orchestra.” John didn’t play anything on the album, except for his voice. And I thought, ‘Jesus, this is no good.’ I mean we’re going to destroy the essence of the whole thing here. I had nothing to say about it because, as I said, we were busy on the road. But I just thought it was the wrong thing to do.

Harry Chapin (From The Tonight Show – September 9, 1975): The thing is that you really can’t make up as good things as a writer that really happen to you. Like a song on the last album I wrote was about a truck crashing with 30,000 pounds of bananas in it and I remember — true story in Scranton, Pennsylvania — and…I wrote a song about it because the old man sitting next to me as I was coming through Scranton on a Greyhound bus looked up to me and said — he had no teeth, I suddenly realized — he said, ‘Can you just imagine all them mashed bananas?’ You know, it was sort of a freaky concept so I wrote a song about it … It’s turned out to be sort of an underground classic. I mean it’s played on a lot of the FM stations. It just never became an AM hit because it’s a little too long…

Sandy Chapin: “[30,000 Pounds of] Bananas” is actually serious. It was kind of a tone poem when he first used to do it. Steve would play the piano and he would perform it almost as a spoken word and then he put music to it and people would laugh. He was writing this as a comment on numbers — I mean God knows it was mild back in those days, but nobody was an individual identity anymore. You were a social security code and a credit card number and a telephone number and a statistic, statistic, statistic. So that was his comment on numbers, thinking that he was taking the humanity out, and it was very serious and then people started laughing. Then the audiences turned it into the kind of nutty thing with the extra verses that it became.

Howard Fields (Drummer): I don’t think (chart success) changed (Harry) that much except to have the knowledge that he had more power and more leeway to do better and bigger things outside of the musical arena. I think that’s where he really started thinking about politics, after “Cat’s in the Cradle” was a hit. He was playing for 3,000 to 5,000 people a night instead of a thousand, 1,500 people a night. His audience doubled and a good handful of cities went way beyond doubling, so I think he realized that there was great potential there and not just to play more concerts for more people.

I think he was larger than life when he was playing for a thousand people as when he was playing for 10,000. It was the same thing. It didn’t matter. He was just so energized always.

***

Big John Wallace: Right from the first album (Steve) was playing keyboards and being involved in the production. He wound up producing a few albums. I don’t remember now how many or which ones, but he has serious musician chops. He became very much involved in the arrangements too.

Tom Chapin: Harry was trying to write the best stuff he could write but I don’t think he ever did it the way that say Springsteen did it or some other people who are fully musicians all the time. He would write something and say, ‘That’s the record, let’s go record it, and meanwhile I’m doing World Hunger Year and I’m doing this and I’m doing that, I’m doing this’ — you know, it’s a different head. Yes, he wanted to be the biggest thing in the world, but he didn’t.

Howard Fields: We actually did our first show March 31, ’75 and the Broadway show was still on. It was a Monday night show which on Broadway is a dark night. That was the Arie Crown Theater in Chicago.

At the first concert I was 24. That was the first time I ever set foot on stage in front of more than a couple of hundred people, well outside of the Broadway show. But it was sold out. I think it was about 3,500 seats. Chicago and Detroit were Harry’s biggest towns. It was a night I’ll never forget.

We did that one show, and then I think we came back and we found out that the next day that the show was closing, that this would be the last week. But again, that wasn’t the worst news to me because I was much more interested in touring around the country with a prominent pop artist. So they booked a couple more shows in April. It was an experimental basis for a short time after which we were told that this is it, you’re in the band. It just peaked from there. An awful lot of concerts. He started booking shows once that Broadway show was over. It just didn’t stop until the very end.

Jason Chapin: A lot of times he would do a concert somewhere in another state and then he would fly home very late at night, and come home in the middle of the night. I would sometimes hear him come home but then I would get up and go to school and then he would still be asleep. Then he would go off to meetings and then leave for another concert.

I’ve got a theory about (Harry) and his calling. He was very much inspired by and very much enamored by people like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. I think he felt that they were willing to go against sometimes conventional wisdom or against what would have been best for their career because they were passionate about their causes. Pete Seeger being blackballed, I think my father really respected him for that, that he wasn’t a sellout; that he really had his convictions and he had his passions.

Josh Chapin: I think Mom realized that, like this was what he was shooting for his whole life so she let him go on the ride for a few years. But two things were born out of that. A…you got to get involved in something and you can’t just be running around charming ladies and playing an extra song, so you got to be about something so that happened as early as Point Lookout. There was a guy named Allard Lowenstein that he got involved with his campaign. So that’s how early that started, and he admitted that that was mostly at the behest of and with the general nudge from my mom.

The second thing was definitely you got to be home a little bit more. There’s a contract — I think it’s from ’78 or something like that — that says, ‘In December of ’78 I will only do 10 concerts.’ But yeah, my mom was always saying like, ‘Listen, you can’t just be all over the place. You got to put at least four days in a row or five days in a row at home.’ So yeah, it was definitely an ongoing thing.

Neither of them were like loud or fighters or anything like that, but to me what was probably really a very serious discussion about Harry — ‘You’re breaking my heart. You got to stay home a little bit more.’ It was not necessarily dramatic, or upsetting, or volatile in any way. But it was happening.

###

Share your feedback with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.