By Ira Kantor

Photos Courtesy of Chapin Productions LLC

The life of Harry Chapin, charismatic musician and iconic humanitarian, was unexpectedly and tragically taken on July 16, 1981. He was 38 years old.

A human dynamo whose sheer tenacity landed him on the Billboard charts, on Broadway, in the White House, and at the forefront of the world hunger movement, Chapin lived by the mantra of “When in doubt, do something.” In following this mentality, Chapin’s 10-year solo career encompassed more than 2,000 concerts, nine studio albums, the creation of global nonprofit World Hunger Year (now WhyHunger) and the love and respect of fans, fellow musicians and key political influencers alike.

Hailed as a consummate musical storyteller, Chapin is best known for his character-driven tunes —“Taxi,” “Sniper,” “W-O-L-D,” “A Better Place to Be,” “30,000 Pounds of Bananas” and “Cat’s in the Cradle” included. Yet despite having only four Top 40 hits to his name, Chapin’s songs remain one of a kind — elevating him to the same artistic status as classic singer-songwriters of the era like James Taylor, Jim Croce, Gordon Lightfoot and John Denver.

Nearly 40 years after his death, the following 10-part oral history seeks to tell Harry Chapin’s story through the firsthand, on-the-record testimonies of the “characters” who knew him best — more than 50 family members, friends, business and political associates and musical contemporaries. For added context, Harry’s own voice, along with other relevant news articles and reviews during his lifetime, are included in italics.

While there are other individuals and events crucial to Harry’s tale who were unable to be interviewed or showcased for this series, this still seeks to provide a well-rounded retrospective of a man whose life, being, sense of accomplishment and legacy remain unsurpassed to this day.

***

Chapter I

Rex Fowler (Musician, Aztec Two-Step): Everyone loved Harry. If you met Harry, you just had to love the guy.

Livingston Taylor (Musician): I certainly was aware of Harry’s career. I, like millions of other people, loved his storytelling.

Janis Ian (Musician): The world lost one of the kindest hearts in the music business when he died.

Gordon Lightfoot (Musician): He had a great personality and a wonderful talent to back it up. And the guts to carry it off.

John Hall (Musician, Orleans): He was a populist back when that word meant ‘of the people, by the people, for the people.’

Jackson Browne (Musician): I actually don’t think that (Harry) was quite nearly as well-known alive as when after he passed away with his commitment to ending world hunger. He was kind of here and then gone.

Ron Palmer (First Guitarist): Harry was a human dynamo. I mean if they could have hooked him up to electricity, he probably would have powered New York.

Ken Kragen (Second Manager): This was one of the great human beings of our generation. And I must say that Harry Chapin was really one of the most unique individuals I’ve ever known — both in his dedication to his craft and humanity in general.

Jaime Chapin Miller (Daughter): Harry was committed to all things that came his way – parenting five kids; learning new things; lobbying Congress; making commitments to people and causes. He believed life was short and had to be lived every minute to the fullest.

David Soul (Actor, Musician): I knew Harry for a long time. You could say there was a mutual admiration on both sides, I think. He writes about real-life stories, which I really appreciate.

John Oates (Musician, Hall & Oates): His songs had a universal appeal. He talked about universal topics but he brought them in a way that was very personal. I saw the way he could take some very, very large subjects and make them feel as though they were just a slice of everyday life. I felt he was really skilled and adept at that.

Oscar Brand (Musician): It was a very, very exciting business meeting Harry Chapin. Without question you could feel he was wrapped in electricity and excitement.

He was a good, sweet man and there aren’t that many. Also, by the way, in not only being sweet and fine and helpful, he was a great musician too. That’s very important.

Jason Chapin (Son): A lot of people have a great life and they are famous for something but they are soon forgotten. The fact that he’s remembered by so many people and appreciated by so many people years after he’s died is just sometimes very hard to believe.

***

STORY OF A LIFE

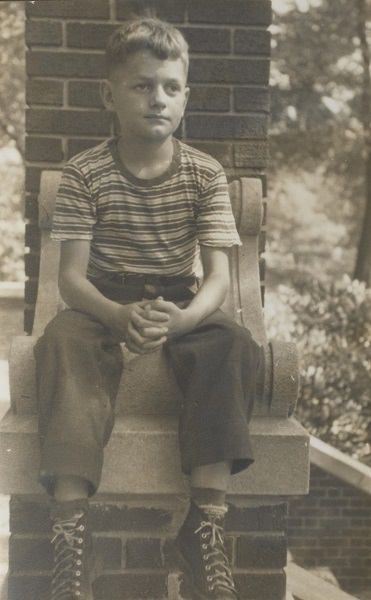

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): Arrived December 7, 1942, the obligatory first step to a life story. I become part of a large, exciting, sprawling, multifaceted brood. The second of my mother’s six sons, followed by three more boys and three girls from my father’s later marriages. A “rich little poor boy” childhood — with few creature comforts, but a family that provided all the love and stimulation I could absorb.

Childhood in New York City in the 40s — on West 11th Street by the Hudson River Piers. Lived in a three-room apartment above a longshoreman’s office on a block halfway between the maximum security federal penitentiary and the M&M Trucking Company. But each summer, for three magical months, we escaped to Grandfather Burke’s farm in New Jersey. No extra money was available in a family of artists, but still all the kingdoms of the mind were opened early — where every mental space was touched upon, except boredom.

Elspeth Hart (Mother): I think I had four children by the time I was 26. I knew [Jim Chapin] before he drummed. I was 14 and he was 15 and we had this house in the country in Andover, New Jersey. My father knew Jim Senior, and Jim Senior played tennis marvelously. Jim Senior came over out to our country place with this very tall, lanky boy…so we met that way.

Bob Zachary (Former Elektra Records Producer): Jim Chapin…invented a drum method way before guys like Joe Morello, who played with [Dave] Brubeck. It was basically learning how to play independents.

Tom Chapin (Brother): My dad was out of the family when I was three. Hugely important in our lives were the two grandmothers — Abby Chapin, who was my father’s mother, and my mother’s mother, Lily Burke.

Our lives early on were a big family thing during the year with our grandmothers who we would see several times a week, every week. Then in the summer we’d spend the whole summer in Andover, New Jersey, with my grandmother at what was called “the compound” or “the farm” out there. As soon as school was out we were there.

Sandy Chapin (Wife): Harry felt he had to earn respect in his own family and to find his position because there were assumptions that his brother James was the brain — uncontested position. His mother perceived that her first-born was going to be another Kenneth Burke.

Harry was, from everything I’ve ever heard, the most delightful child. He was friendly. He was enthusiastic. Playful. Happy. Then there was Tom, and Tom was the all-American basketball player; the handsome athlete. And then there was Steve, and Steve played five instruments and was a musical genius.

Tom Chapin: When Harry was a kid he almost died several times because of his asthma, or at least we thought he would.

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): The 50s brought changes…A stepfather appeared on the scene and we moved to Brooklyn Heights.

Elspeth Hart: The National Board of Review of Motion Pictures decided to get out a magazine called “Films and Review,” and I was the editorial secretary.

My second husband, Henry Hart, who also was a writer and was much older and really was not a very good stepfather, had gone through a thing of being radical and then had seen the light and become – I don’t know if reactionary is the word — but had gone back.

Considering I had four children in all this, I was really very naive. He was nice and educated and attractive. But we were just of such different backgrounds. He’d grown up in Philadelphia, and he was a writer and he really couldn’t deal with these four little boys.

Harry liked to have people approve of him when he was a child. He really liked to please people.

Tom Chapin: My father, we’d see every weekend but was very much not a father. More like a favorite uncle. He’s not a father who’s going to teach you how to whistle or go fishing with you. He was totally into his own world, but we adored him.

The four brothers got very, very tight, and then Henry Hart came into the picture and it was difficult for us and for him, I think. He was a mainline Philadelphia guy. Very interesting guy but totally unequipped to take care of and be the father of four ruffian little guys. He was very much a stickler for manners. He was very proud of the fact that John Hart, his direct ancestor, had signed the Declaration of Independence.

He bought a brownstone in Brooklyn for $16,000 and we moved to Brooklyn — 45 A Hicks Street. It was touchy for us, and Harry was the focal point of the touchiness. They just did not get along at all. No matter what Harry did it was a problem. James, the oldest, would intellectually engage Henry and try to talk to him that way, but it was very hard for us all.

Elspeth Hart: My marriage was not very good, to put it mildly, and I had two new little boys by that time.

Tom Chapin: Dinner would start out fairly mellow and then he’d have a full decanter of wine. By the end he’d be angry at somebody. Usually Harry. Every time it was a Harry birthday, especially when he was a teenager — December 7 — there would always be a war. One year — I think it was when he turned 17 — Henry kicked him out of the house and (Harry) walked from Brooklyn over the Brooklyn Bridge…to the Village and knocked on the door of my mother’s sister.

Elspeth Hart: We moved out one day without saying we were moving out. Henry came home and we weren’t there.

***

THERE ONLY WAS ONE CHOICE

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): I joined the Grace Church Choir with younger brothers Tom and Steve, and started taking trumpet lessons. The summer of ’57 brought two gigantic discoveries, girls and guitars. At my cousin’s barn a copy of The Weavers at Carnegie Hall played constantly, and the trumpet lessons faded away. I find an old banjo in the attic and start playing. Tom buys a guitar, and Steve starts playing four string tenor guitar, tipple, and a stand-up bass. Folk music, the ultimate social weapon, becomes my full-time passion.

Tom Chapin: My Grandma Chapin, Abby Chapin, really wanted us to know the language of music. When we were in the Village we started going to Greenwich House Music School on Barrow Street. Harry took trumpet. I took clarinet under duress and Steve and James both took piano. We learned how to read music.

When we moved to Brooklyn, I went to P.S. 8. We were half a block from the school and in the early fall of that first year — I guess I’m 8 years old — and one of my classmates said, ‘I’m going to try out for a boys choir at Grace Church.’ I made the mistake of telling my mom that he was going to do that, and she got very interested. She found out when (the audition) was and made the phone calls.

That Thursday I got dragged the length of Brooklyn Heights. All the way I’m going, ‘No, I don’t want to, no,’ and she’s grabbing me: ‘Yes you are.’

Big John Wallace (Bassist): Grace Church in Brooklyn Heights was one of the great choirs, at least in Brooklyn. I mean you actually got paid.

The choir director, Anne Versteeg McKittrick, was an amazing woman. She had just as much of an effect on all of us as our parents did. Maybe even more in certain circumstances. A total authority figure and she was just great. Ran the thing with an iron fist. All the little kids were scared to death of her because she could be tough, but it was a great experience. I kid around about it on stage now but my career in a sense did peak when I was 12. I was the soprano soloist in the choir. That was really cool.

Harry was never in the choir. Tom is two years younger than I am, Steve is three years younger so that’s a big age difference when you’re 9 or 10. I think I came in in ’52 and Steve came in about three years later, ’55, so that’s when we met. I mean we could play around or whatever but that was a big age gap then. I didn’t really get friendly or really close to Steve until much later. It was after they went to college and all. Anyway, we got a great musical education there.

Tom Chapin: Also in that choir was Bobby Lamm — Robert Lamm — who would be the lead singer for Chicago. We were all involved until we went into college, all the way through because once your voice changed you became an alto. So it went from 1953 until I went away to college in ’62, so that’s what, nine years? Steve was there longer — two more years.

The music thing, we were steeped in it and also you’d see your dad play every once in a while.

He’d come into our lives and you’d see him at a jazz place. Here’s this beautiful man having a great time behind the drums. Took it totally seriously but also just loving it. So it was kind of an example of a guy who had the most fun in the entire world playing music and dressed to the nines as you did in the Big Band era and just enjoying it. I can’t tell you how important that was for us.

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): In 1958, the Chapin Brothers, singing three-part pubescent harmony, go public for the first time. Reaction is generous enough to sink the hook in deeper. Soon there are $20 gigs at neighborhood parties, band breaks and society dances. The Chapin Brothers become junior folkies, on the periphery of the Greenwich Village hotbed of an exploding folk boom.

Tom Chapin: Grandma Chapin had an old Stuart banjo in her basement that had been her brother’s. Harry got it fixed up and got the Pete Seeger book and began to play. I got my first guitar, a plywood Kay guitar, I think for 50 bucks or something. And we started learning Weavers songs. Then we talked Steve into playing with us. So we had a trio and of course what was really cool about this [is] Harry was the lead dog, the older brother, but Steve and I, because we’re choir boys, we could sing harmony (laughs). Harry was usually the melody guy and Steve and I would do various harmonies. For the next 10, 12 years that was our hobby. We got more and more professional and eventually started playing in the Village and stuff. But it was very much like, ‘Hey we can do this together.’

Stefan Grossman (Musician): We were schoolmates at Brooklyn Tech and I was learning guitar with Reverend [Gary] Davis at that time. Tom was playing guitar and banjo as well. We’d get together to just play. The culmination is we all performed — me, Tom, Harry and Steve, the three Chapin brothers, sort of like a Kingston Trio type of unit, and we did a performance in Brooklyn Tech. That’s when I really got to know Harry and the Chapin brothers. They were all great singers and they could all sing harmonies fantastically well. I was friends with Tom, not with Harry. Harry was older than us.

Tom Chapin: Another connection was that around the corner from us in Brooklyn Heights lived Earl Robinson. I mean we’re doing folk music; we didn’t know who he was. His son Jimmy Robinson is a great friend of Steve’s and they’re getting in great trouble in the Heights, you know. They’re hanging out. Living downstairs [from] Earl Robinson at that time was Lee Hays. Now we never connected it but Lee Hays was the bass singer in The Weavers, and he had a leather couch. Harry was doing leatherwork at that point. So Jimmy told Earl that Harry was doing leather stuff. Harry goes over…and fixes Lee Hays’ couch. We didn’t know who Lee Hays was (laughs) until later on I go, ‘Oh!’ It’s interesting because we were trying to do folk music and then we didn’t even connect with what was around.

Diana Chapin (Sister-in-law): Harry would always be leading the pack. It was like a joke that he would be way ahead of everybody else physically. He’d start off and if you were all in a group he’d be way ahead. Harry was very enthusiastic. (James) used to say, ‘Chill down, Harry,’ because he’d get so over the top enthused about things. It was his nature.

***

OLD COLLEGE AVENUE

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): In 1960, high school is over, and in the next three years I manage to spend three months in the Air Force Academy before resigning, three terms at Cornell before busting out…

Gary Howe (Vice President of the Air Force Academy’s Association of Graduates): Harry Chapin would have been in the Class of 1964. He was here at the Academy as a cadet from 27 June 1960 to sometime in August 1960, which means that he would have been here for what we call basic cadet training and left at the end of that.

Elspeth Hart: (Harry) went to the Air Force Academy. The hazing was absolutely horrible. He couldn’t stand it.

Glenn Coleman (Classmate, Air Force Academy Class of 1964): Your first day there is really scary because you go from being a high school hot dog to really a number where they shave your head and put you in a uniform. There’s just a lot of screaming that goes on for the whole summer. Every moment that you’re there, there’s somebody in your face except at night. In other words when you go to bed at night, you’re guaranteed eight hours and that’s pretty much the only time you have to yourself.

Dave Neal (Classmate, Air Force Academy Class of 1964): We were in the 42nd Cadet Training Squadron. There were probably 30 to 40 classmates in that squadron and then the upperclassmen were in charge of the hazing. We had to march at attention at all times everywhere. At meals we sat on the front three inches of our chair and looked only down at our plate unless we were addressed by an upperclassman who was giving us more attention in meals than we wanted.

Glenn Coleman: You’re going to take one week out of that in the last half and you go to the mountains for survival. In that case you’re living up there for a week. Basically, it’s Boy Scout camp. In other words, you’re out there learning how to skin a rabbit, learning how to find food, learning how to trap an animal, learning how to fish — just learning how to survive out in the wilderness. Even though it’s not highly technical as far as they are not really creating Crocodile Dundee out there, it’s a confidence builder that they are teaching you how to survive.

Dave Neal: I remember a couple of evenings or maybe weekends when we had a few minutes to do something on our own that some of us would gather in Harry’s room and he’d break out his guitar and play and sing.

Elspeth Hart: A dean or somebody at the Air Force Academy in trying to make him stay there said, ‘If you don’t succeed in this, you’ll never succeed in anything else.’

Harry Chapin (From The Tonight Show – August 10, 1977): Actually, I have sort of a mixed academic history because I busted out of Cornell University twice, once in architecture and once … in philosophy. It means that not only could I not build a library, I wouldn’t know what to inscribe around it, you know.

Diana Chapin: Harry flunked out of Cornell at some point and he had gone to the Air Force Academy prior to that for a while. Jim at one point felt badly because at one point he was sort of writing these sorts of letters to Harry and he felt he wasn’t supportive enough at the time. Looking back on it he said, ‘Geez, he was having a hard time and I should have been more supportive.’

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): By the end of ’63, I am in love and thinking I should give one more shot at finishing college. By my second attempt at Cornell, and my first attempt at a love affair follow the same pattern — pyrotechnic beginnings followed by gradual decline. Ironically this educational and emotional merry-go-round makes a fertile climate for my first songs. They fall into the usual categories for young prophets: protest songs and lugubrious ballads of unrequited love. It takes four terms to bust out this time.

James Maas (Retired Cornell University Professor): I met Harry when he was an undergraduate student at Cornell and was taking a psychology course from me. That course had small discussion sessions as well as a large lecture. On several occasions Harry came up to me after lecture and said, ‘I’m in a quandary, I don’t know what to do. I’m struggling with the curriculum in architecture and one of the reasons I’m struggling is because I have always wanted to be a folk singer. Yet I know it’s nearly impossible to make a living doing that, and I think my dad would like me to get some applied degree so I can make some money. But my heart is really in folk singing. I just don’t want to disappoint my father. On the other hand, I feel that I’m leaving something that I’d like to go with.’

I said, ‘Harry, you’re always going to regret not trying and so you absolutely have to devote a couple of years to singing and see how it goes. You can always come back and be in architecture and get further education. But now is your time and follow what’s in your heart. If you’re good, you’re going to be successful. If you’re not good, at least somebody will tell you you’re not going to make it and then you can have that to make further decisions.’

We had that conversation I’d say three or four or maybe five times.

Tom Chapin: We had a stepfather who we really hated, but we had this other incredibly valuable creative physical clan. The music really was an outgrowth of this incredible artistic family clan. That’s where it started. Harry, when he was at Cornell, got involved with the Sherwoods who were sort of like the Whiffinpoofs. They’re Cornell’s a cappella group. He was always trying to be in that group but again he was not equipped for it. But Fred Kewley, who was the head of it, became a really good friend and Harry’s first manager.

Fred Kewley (First Manager): It was 1961 and as freshmen at Cornell we both were intrigued with this a cappella singing group called the Sherwoods. We both tried out and against all odds we both got in. (Harry) was with us maybe two months or something and then he bounced out of school. He just wasn’t doing well with school. Over the years he came back to Cornell and studied architecture and bounced out, came back and studied something else, and bounced out. He never did finish.

He’s the first guy that I had ever known personally that could play guitar and actually put a song across playing guitar. This is back in ’62, ’63. This is coming off the folk days with the Kingston Trio…so to be able to do that was very impressive. Even back then in those college days, he would lean over that guitar and stare you right in the face and just completely sell you on whatever song he was singing at the time. He was always a super salesman when it came to most everything, but especially in putting his songs across and making the listener just get into it. He wasn’t background music in any way.

I lived with Harry, Tom, Steve and James and their mother. I think it was a two bedroom, one living room, one kitchen apartment in Brooklyn Heights for like three months.

They are all loud. Steve used to say about Harry: ‘Two is company and Harry is a crowd.’

***

Harry Chapin (From an unedited typing exercise, February 1964): Yeah, I sing with my next two younger brothers, and we are going to make a million dollars, or so we think…

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): By 1965 I’m beginning to realize that I am not going to progress through life following the normal patterns. My brothers and I decide to get serious about our music. All the guitar playing that has been a crutch to our social lives, that has made us a couple of bucks on the side, that has given us something to do besides drinking beer on street corners, now is put to the test. We resolve to become full-time professionals. It’s a summer of airborne [sic] dreams, potentials and performances, and yes, it felt like somehow, somewhere, sometime we were going to make it.

Dad joined the group that summer and backed us up on drums. We were still green but we were definitely different: part folk, part rock, topped with Grace Church harmonies and a jazz beat from the old man swinging in behind. But in September, Vietnam forces Tom and Steve back to college, and I’m back at square one.

Tom Chapin: Dad was recording for Music Minus One. He knew [owner] Irv Kratka, and that summer Irv Kratka came and saw us play. He offered us studio time, but basically it was like Dad was playing with us. Also at that point [drummer] Phil Forbes was playing as well, and he was more of a rock drummer. He’s on the record (Chapin Music!) too.

In like three days we went in and recorded 12 songs, 14 songs, whatever is on the record. It was kind of a blur. We just get in front of a microphone and just bash away and sing it and then, ‘OK, that’s that one, let’s do the next one.’ It was basically what we were doing live and then we overdubbed something.

Here’s an interesting story you may or may not have heard. September or maybe early October of my junior year, I believe, the Chapin Brothers are going to play at Hawkins Hall and we sold out Hawkins Hall, which is 600 people at the hall in Plattsburgh. It’s one of those things where everybody came and they’re all saying, ‘Geez I hope this is good; it’s Tommy.’ We get out there and start that first number and it was called “Walk Tall,” and then Dad comes out on the drums towards the end. And we ended it – a standing ovation. The whole thing was a brilliant thing.

That happened on Saturday night and on Monday we were supposed to try out for a new TV show called “The Monkees” in New York City. We’re driving home and Dad has this Studebaker with his drums up on the roof and in the back it’s full of our guitars. Steve is taking the bus. Dad’s driving and Dad very often had tires that were like threadbare. After we get down to Albany — Harry’s got his learner’s permit — Dad says, ‘I’m getting tired, do you want to drive?’ He says, ‘Sure.’ He gets behind the wheel and we’re near Cairo, New York on the thruway, cars all around us and bus behind us. We’re going about 60, 65 miles per hour on the thruway — right rear tire blows and Harry’s driving. I’m asleep on the back seat across the back seat — this is before seat belts, you know, and Dad’s in the suicide seat. And it goes ‘BOOM! DU DU DU DU!’ and Dad says, ‘Don’t try to steer out of it,’ and Harry turns and the car rolls once off the road, twice — I’m holding on with my feet against the roof – three times. Comes to a halt…My dad reaches over and turns off the thing. I start kicking the door to get out, and Harry has broken the steering wheel with his jaw. And my father, the whole thing kind of caved in on his head. It turned out later his neck was broken but he didn’t know.

What saved us was the drums on the top.

Dad, when he was a kid fell out of a tree and his top three vertebrae in his neck are fused from that so they take an X-ray of his neck; it looks like a normal neck. What actually happened was he broke all of the fuses left there and for the next month he’s in terrible agony. It’s funny, his mother sent him to a specialist and he has to wear one of those braces around his neck.

Tuesday we go in to try out for “The Monkees” and Steve’s there. We open up the guitars and the back of (Harry’s) Martin was totally busted. We hadn’t even looked at it. So we sang our stuff and they’re kind of interested in me but not the band and that’s as far as it went (laughs).

In another life I might have been Peter Tork.

Fred Kewley: Tom Chapin called me out of the blue one day. He had a group called The Chapins. They had gotten a deal with Epic Records. They were on Epic but Epic didn’t seem to even know they existed and their manager at the time wasn’t getting anything done so Tom called me and said, ‘Do you want to manage us?’ I mean out of the blue. It’s probably one of the smarter things I had done up to that point.

From The Night That Made America Famous Playbill, February 1975: After busting out of the Ivy League twice there was a brief fling at music in 1965, complete with father Jim Chapin on drums — it was sort of hip version of the Partridge Family. This fun time ended too quickly because of the Vietnam Draft — Tom and Steve had the choice of either going back to college or fighting for Thieu in the rice paddies. Harry, who was an Air Force veteran, went into film, started out packing film crates. He worked his way up to editor, cameraman, then, to writer, producer and director.

Harry Chapin (From a 1980 concert program): A film job surfaces and it’s six months in L.A. making airline commercials. Then back to N.Y. to work on boxing films with Cayton, Inc. For the next two-and-a half years I immerse myself in the history of the fight game and by the Spring of ’67, I tackle a major project, “Legendary Champions,” a theatrical documentary feature. It later wins the New York and Atlanta film festival gold prizes as best documentary and is nominated for an Academy Award as Best Feature Documentary.

Then it’s off to Ethiopia with Jim Lipscomb for a documentary on the World Bank’s impact on the underdeveloped world. But again, I leave the film business, this time to try writing a Broadway musical During that summer and fall I write the first four versions of a musical (the ninth version opened on Broadway in 1975).

###

Share your feedback with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.