By Ira Kantor

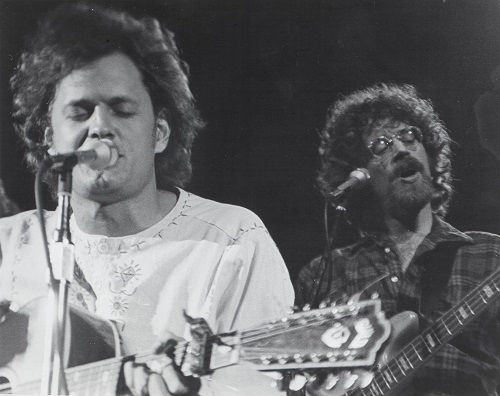

Photos Courtesy of Chapin Productions LLC

The life of Harry Chapin, charismatic musician and iconic humanitarian, was unexpectedly and tragically taken on July 16, 1981. He was 38 years old.

A human dynamo whose sheer tenacity landed him on the Billboard charts, on Broadway, in the White House, and at the forefront of the world hunger movement, Chapin lived by the mantra of “When in doubt, do something.” In following this mentality, Chapin’s 10-year solo career encompassed more than 2,000 concerts, nine studio albums, the creation of global nonprofit World Hunger Year (now WhyHunger) and the love and respect of fans, fellow musicians and key political influencers alike.

Hailed as a consummate musical storyteller, Chapin is best known for his character-driven tunes —“Taxi,” “Sniper,” “W-O-L-D,” “A Better Place to Be,” “30,000 Pounds of Bananas” and “Cat’s in the Cradle” included. Yet despite having only four Top 40 hits to his name, Chapin’s songs remain one of a kind — elevating him to the same artistic status as classic singer-songwriters of the era like James Taylor, Jim Croce, Gordon Lightfoot and John Denver.

Nearly 40 years after his death, the following 10-part oral history seeks to tell Harry Chapin’s story through the firsthand, on-the-record testimonies of the “characters” who knew him best — more than 50 family members, friends, business and political associates and musical contemporaries. For added context, Harry’s own voice, along with other relevant news articles and reviews during his lifetime, are included in italics.

While there are other individuals and events crucial to Harry’s tale who were unable to be interviewed or showcased for this series, this still seeks to provide a well-rounded retrospective of a man whose life, being, sense of accomplishment and legacy remain unsurpassed to this day.

***

Chapter III

HEADS & TALES

Jac Holzman (From a 1971 advertisement for Heads & Tales): Harry is…a music and a band. Harry is a storyteller and if I may coin a word, an evocateur. His songs, in which “Taxi” is a superb example, are a marvelous unity of memorable melody and finely wrought lyrics. Harry’s album, which we are now completing, will be ready to ship February 15. He is a major discovery and we expect him to have the same kind of initial public impact as did Carly Simon. Harry’s album marks my return to the studio as a producer.

Big John Wallace (Bassist): (Recording) took a long time. I think we were there for a couple of months for that first album.

You’re under the microscope. I was very self-critical at the time, so I didn’t like anything I was doing. It’s almost like you’re playing defensively or you’re not trying to lose rather than being on top of it and having fun playing, you know. That’s just the way it was for me, I’m not talking about anybody else. I mean especially, because we had the great Russ Kunkel [on drums]. That was the part of it that was really cool for me, to play with somebody as good as he was. It’s like having kind of big, strong arms holding everything together.

Tim Scott (First Cellist): We had the luxury of spending a lot of time [in the studio]. (Harry) would go over things quite a bit until he got the voice just the way he wanted it. I remember one song called “Same Sad Singer” which Jac Holzman was actually the engineer for because we did it like very late in the middle of the night. We did three tracks of the cello. It was very tiring. He was somewhat driven in the studio and somewhat of a perfectionist. I don’t remember like hating him, I know that. I don’t remember that being a big problem but we took our time. We never rushed in the studio. I remember we had this drummer Russ Kunkel, who was some well-known L.A. drummer there and was very good. That certainly helped us out some.

***

Sandy Chapin (Wife): He’d pick up $100 here, $100 there for something but the money ran out. All of a sudden there was a recession. There was nobody looking for him for a documentary and that’s when he got a hack license. And the day that he got assigned to this garage, three different film jobs came in and then he did some training films for IBM.

He never drove a cab.

Ron Palmer (First Guitarist): It was Harry who wrote the song [“Taxi”] and was still writing it when we went in the studio.

Robert Mrazek, (Friend, Former Politician): His songs usually involved loss and the loss of one’s hopes when they are young and they get older and things don’t turn out the way they planned, which is the foundation of “Taxi.” “She was going to be an actress and I was going to learn to fly,” and neither one of them are happy in their lives. There’s this poignant moment at the end where she gives him a $20 bill and he no longer has the pride to reject it and simply stuffs it in his pocket and goes on. A loss — unlike Harry’s life. One of failure.

He gave you these peoples’ lives — broken as they were.

Niles Siegel (Former Elektra Records Album Promotion Man): Harry’s record was a particularly difficult one because it was like forever. It went on for a couple of months. It just never ended.

We had real problems with (“Taxi”) because as much as people loved it, one of the major markets in this country in terms of Top 40 was San Francisco and he was driving his cab in “Frisco.” “Frisco” was derogatory. We had to fight like hell and beg and plead and practically get on our knees to get that record played in San Francisco so we could make Top Ten. San Francisco wouldn’t touch it.

I remember this so well because it was such a battle and it was so difficult, and the reality of it was the program director at the Top 40 station in San Francisco, was a guy named Sebastian Stone who happened to be one of my dearest friends. [He] said, ‘Niles, I can’t play this record. They’re going to chew me up and spit me out here if I play this record, calling San Francisco “Frisco.” I can’t do it.’ Eventually the record was selling so well and it was just taking off so beautifully that he had to. But that was one of the problems, the length. Nobody wanted to play anything longer than three minutes because it didn’t fit the format.

Eric Bazilian (Musician, The Hooters): I remember when “Taxi” came out, how the characters were so alive to me. (Harry) was actually one of the very few “troubadours” of the time of whom I never tired of.

Fred Kewley (First Manager): I remember the summary of the conversation was, ‘Give me three for the radio and the rest of the album you can have.’ I can say that early on he was writing songs that people liked that were not necessarily at all designed for the radio. The first hit he had was “Taxi,” which broke all the rules. Of course “American Pie” did really well too but it was really exceptional to have a six minute and 44 second single on the radio because the big stations then — and there were eight of them that really mattered in the country — if it was over three-and-a-half minutes they just said they wouldn’t play it. So that was something we learned.

I’ll say that first album did well. We got ourselves in business and then we were pretty self-involved after that on the second album.

Sandy Chapin: I actually wrote a poem about it. It was like (Harry) was going to move to Mars. We had such a close relationship over writing and words and he worked on everything I wrote and I worked on everything he wrote. I mean it was so close and so invigorating and I remember when we first went to Jac Holzman’s place in upstate New York and Jac brought him into his home studio and I saw that machine with all those boards and buttons and I thought, ‘Oh, uh oh.’ It was really, really scary.

Tom Chapin (Brother): The whole thing was not only surprising but it was thrilling. The thing that’s interesting about this is it’s not like this is an unknown. I never felt like, ‘Why isn’t this me.’ That didn’t even occur to me. I mean I was already doing “Make a Wish.” Harry bought his house because I got him the job as the writer on “Make a Wish” that same summer actually. It was a very fertile time. I’m filming all day, five days a week in New York City – the same time we’re doing the Village Gate at night.

He wrote “Circle” for that and a bunch of songs. So it was surprising and wonderful and thrilling. It was like, ‘Wow, look at this happen,’ but it wasn’t like, ‘That should be me.’ That didn’t even occur to me or Steve. We grew up with Harry. Nothing was surprising with Harry. My quote that the family loved at the time was, ‘Two’s company, Harry’s a crowd,’ and we used it all the time. I mean in some ways we were incredibly competitive but I mean the music is what we did together. It was a collaborative event.

Ron Palmer: We went out there in the first part of December and we worked right up until a Christmas break or something. Then later on we had to go back to Los Angeles and finish a couple of things or change a couple of things. Then it was like a month or two later when we went out on our first tour.

Big John Wallace: I remember specifically when I touched (Heads & Tales) for the first time. We were in San Francisco. A carton of them came in and I opened it up and held it in my hand for the first time — the shrink-wrapped version — and that was an amazing feeling. I’ll never forget that. That’s when you really got a sense of the accomplishment of what just happened.

Put it this way, financially the first year we made $6,000 or something but of course that was just half a year. Year two, we made $11,000 or something and it kept inching up like that. We played gigs here and there. I guess we started to do colleges but this is before the record came out. The first gig we played after the record came out, I remember, was in Champaign-Urbana. The audiences had responded tremendously to Harry all along. It’s because he lays it all out there, you know. You can tell he’s giving it everything he can, so the responses are always good. But we walked out on stage this night after the record had been released and the crowd just went nuts. Like a standing ovation when we were walking out. We just kind of looked at each other and said, ‘Wooo, things are a little different now.’

Jackson Browne (Musician): I saw (Harry) at the record company. Of course, he was unmistakably him. He was great. He seemed exactly like the guy in the songs. He seemed very friendly and down to earth. And kind.

Tim Scott: We did a tour for Elektra Records. We opened for Carly Simon at the Troubadour. What I remember about that is she introduced her friend James Taylor, who was very big at the time. We opened for Cheech and Chong at The Bitter End in New York. We opened for the comedian David Steinberg, I think, at a big comedy club in Chicago and then around the country quite a bit. Then we just toured around a lot of college campuses or odd places around the country. College campuses, gyms, that type of thing. Some very nice concert halls too as I recall — Kleinhans Music Hall in Buffalo, a big one in St. Louis.

John Oates (Musician, Hall & Oates): We did actually play together. When Daryl and I first started, and I believe it was in ‘72, we opened for Harry Chapin at The Troubadour in L.A. He was a really cool guy. We actually got him to come on stage with us and do this really funny, kind of crazy song that Daryl and I had written. It was called “Whistling Dave.” We never recorded it. It was almost like a jug band song and I guess he had heard us doing it during soundcheck as a joke because we weren’t really playing it in our set. For some reason, I think he liked it and he said something about it. We said, ‘Hey, do you want to come up and sing it. We’ll do it.’ And he came up — we were opening for him but he came up during our encore which is very rare for a headliner to do that. I thought that was really cool.

Fred Kewley: We got that album done and Jac started going to the trades, the Billboards and the rest of it, talking about Harry over and over, doing all kinds of interviews. Just like the biggest hype you ever saw — that Harry Chapin is the next whatever, the next big thing. And then Elektra had a convention and it was in Phoenix. Harry was going to perform for the first time there where the industry would see him, including all the artists on Elektra Records, and all their managers, and all the agents and all the rest of it. It was kind of a big inside deal at this Elektra convention and Jac had actually laid everything on the line. I can tell you that every time there was a situation like that where it was a pressure situation where Harry had to do really well to not make it a total fiasco he always came through every time. He just knocked them over there at that convention.

Rex Fowler (Musician, Aztec Two-Step): Harry was, as you can imagine, a larger than life character. He was Kennedy-esque.

“Taxi” had really made some noise. The shows were all sold out. I don’t know if that many people were aware of us. We did certainly bring some fans into that but our record had just come out. We were promoting the record whereas Harry had already made his splash. He was headlining, bringing people in. If we had headlined we would have had 15, 20 people. It was always sold out. It was very exciting because the place was packed every time you went out on stage. We always held our own. His fan base was very respectful and enthusiastic about us, so that was nice. We had a smattering of fans in there because we were just getting some airplay on FM radio as well. It was a nice double bill.

Fred Kewley: After “Taxi” came out, we went out to do the first Johnny Carson show. He’s backstage behind the curtains and the air-conditioning is up full blast. Everybody is shaking in their boots — nerves, cold — and the curtain opens and there you are. Whatever he did, he did that equally well to the convention. The crowd went crazy.

We were out in the parking lot after the show packing up and Fred de Cordova, the producer of the show, came out and he said, ‘Guys, we have absolutely never done this before but what are you doing tomorrow night? Can you come back tomorrow night and do it again?’ I think (Harry) was definitely the first at that point and probably the only artist like that to do two Tonight Shows in a row, especially being his first and second.

Sandy Chapin: I always had this romantic picture of Harry, of the American troubadour that traveled around the country carrying his songs. He stood up and played his songs. He went to the college or downtown where he hung out and he picked up another story and wrote another song and took it to the next town and so on and so forth. I mean his songs cover real people and real places all over the United States.

Fred Kewley: I got a call from our agent early in the game. We were all up in New York; he said, ‘I have an offer for you to open up for the Temptations in El Paso, Texas tomorrow night.’ I called Harry and he says, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’ So we just rounded everybody up on like 24 hours notice, if that, flew down to El Paso, did the show, flew back. The agent said, ‘You’re the only act that I got or ever heard of that would have done that.’ That started with Harry. I mean he was the one who would do that.

Tim Scott: What he did with us…that I did appreciate [was] the financial arrangement. From all the concerts, we split the money four ways and he just got the money from royalties if other people sang his songs, which does seem completely fair. We were treated very well in that way.

Big John Wallace: This is one of the first things that he did. I guess maybe we were in a diner in Brooklyn Heights. He kind of laid it all out. He said, ‘Guys, I don’t have any money.’ He said, ‘I can’t pay you money now. We’re not going to be able to have any money until we start making it ourselves so I can’t give you anything now. But what I’ll give you is a straight four-way split. Everybody gets 25 [percent], including me.’ And that was it. That was a handshake deal — boom. That was it, and that’s the way it stayed. Of course, management and agents got their cut off the top but he never reneged or tried to renege on that deal. But he also said — loyalty was very important to him — he said, ‘If I fire you for any reason, you’ll keep getting whatever you’ve earned, but if you leave, you’re going to forfeit it.’ So at the end of three-and-a-half years when the Broadway show came up and Ron left, he left knowing that he wasn’t going to see any more money.

From a 1972 Rolling Stone review of Heads & Tales: Harry’s story songs are his worst…“Taxi” is, of course, the most famous song on Heads & Tales, and that’s unfortunate because it’s the album’s second or third worst song, and a veritable textbook of lyrical, melodic, and production errors. The opening melody is merely banal, but more seriously, Harry doesn’t know how to construct a story (Interestingly, Harry’s publishing company is called Story Songs, and the word “tales” a part of the LP title.) His method is to build up an accretion of superfluous and irrelevant detail which effectively halts any narrative momentum…Certainly you shouldn’t be prejudiced against Harry on the basis of the unavoidable “Taxi.” Harry’s comprehensive resume also includes some time spent as a stock broker. Maybe his next album will tell us a story about “that.”

***

SNIPER AND OTHER LOVE SONGS

Fred Kewley: Now we’re hotshots because we knew what we were doing now. I produced the [second] album and it was Sniper [and Other Love Songs]. We made an album for us that had a lot of great stuff. I think that song “Sniper” — if you get a chance, you put that on a good sound system and just turn the lights down and get between the speakers and you’ll see it’s an amazing experience. But it wasn’t a three-minute single. We mixed that for 24-hours straight and there were four of us all assigned various jobs mixing it.

Big John Wallace: I think Steve feels the same way that in many ways it’s Harry’s masterpiece.

Josh Chapin (Son): I know I’m in trouble if I listen to “Sniper” and it doesn’t knock me out or hit me on some level like inside.

Marie “Peachie” Marsden (Friend): “A Better Place to Be” is about an old guy and a young girl and they just find each other. They are both lonely so why shouldn’t they be together? What’s wrong with that?

Gordon Lightfoot (Musician): I remember one time I was playing in Britain and I was staying at a hotel there for about three or four days in London. I played (Harry’s) first couple of albums. I played them over and over again and I learned that song “A Better Place to Be.” That was one of my all-time favorites by him. It’s the story in the song that grabs you and then of course the melody and the chords and everything that goes with that.

Paul Layton (Musician, The New Seekers): At this time our record producer David MacKay was looking for songs for our next album. Either (“Circle”) was submitted to him by the publisher or David was aware of the song from Harry Chapin’s recording. It was recorded in 1972 at Morgan Studios in North West London where Cat Stevens recorded. I remember it well because for the extended version…we went out on to the street and rounded up members of the public to come in and do some sing-along choruses and hand claps for the end fade out.

It was most successful in the UK where it reached Number Four in the charts and remained in that position for four weeks, and a total of 16 weeks in the charts. It was in the top 50 bestselling singles of 1972.

(“Circles”) is a highlight of our concerts and I have it on good authority that it remains the fans’ favorite. In the UK…I guess the message is timeless as it has such a poignant lyric. Life does seem to keep going round and round in circles.

Ron Palmer: Harry wanted (Sniper and Other Love Songs) to be a double album. Fred Kewley and Harry basically produced that album, and then of course we had produced enough for a double album. But Jac Holzman just up and said, ‘Harry, the world is not ready for a double Harry Chapin album.’ So that went down the wayside.

From a 1972 Rolling Stone review of Sniper and Other Love Songs: The most that I can say for this kind of wretched excess is that it is impossible for one to remain emotionally neutral to it. Chapin has the courage of his convictions, and the sheer insistency with which he advertises his case of emotional diarrhea does carry some energy and invoke some sympathy…No doubt some will find all of this socially meaningful and even personally cathartic. Harry goes to great lengths in trying to evoke a dark, inchoate strain of American life and make it “art.” What does him in is his own overweening self-pity, which distorts and demeans his apparently sincere intentions.

Jason Chapin (Son): My father took a lot of criticism from music critics. They didn’t think he was that good and they weren’t impressed with his recordings and his concerts. He wouldn’t say anything to us like, ‘This person’s horrible because he wrote a negative review.’ In his concerts he would make fun of himself and say, ‘This is a song that I hope you enjoy more than the critics.’ He was always trying to win them over and he would do lots of interviews with either print or radio or television. He was always trying to get them to appreciate him and recognize his talents. But he also was aware that a lot of them didn’t think that he was as good as his fans did.

Gerry Beckley (Musician, America): That [1973 Grammy “Best New Artist”] category was Loggins and Messina, the Eagles, ourselves, Harry and John Prine so that’s a pretty deep bench for “Best New Artist.”

There was a lot of lovely, incredibly unique stuff happening in the late-Sixties and early-Seventies. One of the great genres is the storyteller song. (“Taxi”) was a fascinating record. When I speak about being at Warner Brothers in those years, I always mention three artists – Ry Cooder, Randy Newman and Van Dyke Parks. There’s three very shining examples of artists somewhat like Harry that were very unique.

There was a place for artists at that time. Labels were proud to have people like Van Dyke even if his numbers weren’t enough to chart the records. These guys were of immense talents and went on to prove themselves in many other capacities. I think Harry clearly was in that category of very, very unique talent.

***

SHORT STORIES

Harry Chapin (From a 1975 concert): I have trouble getting my songs on the radio because they’re too long, but this is a song that snuck on the charts for about 15 minutes…

Fred Kewley: (Sniper) was a good album but there was nothing there for radio and that really slowed us down as far as our moving along with his career. We knew we had to come up with something to get back on the radio. Harry wrote “W-O-L-D.”

Sandy Chapin: After (Heads & Tales) was out, as he was touring and doing small clubs all over the country, he made a point of going into radio stations and schmoozing program directors and disc jockeys, which is what led to “W-O-L-D.”

Fred Kewley: I’m sure we talked about it at the time — ‘Write a song of these disc jockeys.’ See we were traveling around and having lunches and meetings and interviews with disc jockeys all the time and the noticeable thing about most of those was those conversations were almost entirely about the disc jockeys and almost nothing about Harry Chapin. You know, a lot of egos out there. I think he figured it out that if he wrote a song about disc jockeys they’d play it. That was a fairly calculated way of getting back on the radio after the second album.

Robert Mrazek (Friend, Former Politician): “W-O-L-D” is a song about failure. It’s about a man who pursues his career as the morning voice and loses his family and ends up going farther and farther down the food chain until the end when his professional life is over and there’s nothing left in his life. There’s a sense of tragedy about that.

Melanie Marsden (Friend): My father, he had friends at the phone company and he had all the operators call and request (“W-O-L-D”) so that it would flood the station with requests. They wanted it to go gold in Boston.

Fred Kewley: “Mr. Tanner,” I think is maybe my favorite song of his and should be a hit but never has been. I say it should be because it’s good. I mean his lyrics were always very good but the lyrics in that thing are just outstanding. He just paints this picture, a very complete picture in very few words.

From “Tubridy, a Bass-Baritone, Performs in 2d Recital Here,” The New York Times, Feb. 17, 1972: Martin Tubridy, a bass-baritone who came to Town Hall on Tuesday night to give his second New York recital, performed songs by Beethoven, Schubert, Vaughan, Williams, Britten and others. He was accompanied on the piano by Mitchell Williams. Mr. Tubridy’s voice seemed quite limited in amplitude, range and flexibility, and it was probably because of this that his interpretations lacked force and strong communicative power. He was well-prepared and sang conscientiously, but the results were not up to generally accepted levels of professional accomplishment.

Big John Wallace: I think it was Harry’s idea from the beginning. He read a review about a singer from Dayton, Ohio — Martin Tubridy — and here again, you know, empathizing with the downtrodden little guy who got his ass kicked in the reviews. That’s how that one was started.

Why (“Fall on your knees” is) in there, I don’t remember. That was one of the things that we did in the choir — “O Holy Night.”

Martin Tubridy (Inspiration for “Mr. Tanner”): I was not aware for many, many years after, that Harry Chapin had seen a review I had received from a Town Hall recital I did in the early 1970’s and actually had used it as his inspiration for “Mr. Tanner” … In the ensuing years after, I found it very hard to believe that there could possibly be a tie-in to my concert which was so many years ago. In 2016, Howard Fields of the Chapin band contacted me to sing “Mr. Tanner” with the band in Connecticut and confirmed the connection. He also gave the perspective that the song held a special meaning to Chapin fans and to Harry Chapin himself as he had previously received less than favorable reviews regarding his own music from the critics who may have preferred he move closer to rock music.

(Harry) had an incredible ability to relate meaningful and moving messages in his thought-provoking songs, such as “Cat’s in the Cradle,” “Taxi,” and “Mr. Tanner.”

“Mr. Tanner” is an absolutely beautiful piece that really musically creates a compelling story between listener and storyteller with its own deep feeling of hope as the song is completed. It is a song that honors the gifts we are given and [tells us] to not give up. It has become an honor for me to learn so much more about Harry Chapin and all the profound good that he has done for others that are in need.

Tommie Lee Jackson (Musician, Short Stories Backup Singer): I was green. I was still just learning the ropes. But with Harry and the guys, it was kind of like just being one of the guys. Though they treated me like a lady, I was still one of the guys so that made me feel good because I’ve always been kind of a tomboy in working with musicians. They’re all like my big brothers.

I think it took us a week to go through all the things that we played on. I must admit on Short Stories, my two favorite songs are “Mr. Tanner” and “Mail Order Annie.” I cannot listen to those songs without crying. They just evoked such emotion in me.

Harry was such an amazing storyteller. I wish I would have paid more attention to his method of writing or been able to ask him my opinions after we finished the album.

Big John Wallace: He would normally bring (songs) in, especially if he felt good about it. I remember a few years later when he brought “Cat’s in the Cradle” in and he sang it to us in the dressing room one day before a show. I remember thinking when I heard that, ‘Wow, this song sounds great. Something could be here.’

Tommie Lee Jackson: It just made me feel like I was really singing and doing what I was meant to do. He would pull that vocal out of you. He was a good coach in the studio. Sometimes producers count more on what you can do and kind of let you loose. He did that but he would also direct and encourage. You could use your imagination, so that was a first for me. It’s always nice when you can have somebody that respects that.

It was a short story for me with Harry. But it was lovely.

***

Big John Wallace: We all got really close. I mean even one year on the road you’re in the trenches. It’s kind of like being in the war without getting shot at. You’re going through a lot so you bond. Everybody got along really well, especially even with Harry back then because we were still traveling together and he was part of us. Of course, later on, the more and more he had going in his life, then it was a separate thing and we didn’t see him as much anymore.

Tim Scott: Harry was very fair to us but I felt he could be very sexist and a little too aggressive in his personality sometimes. I don’t want to say conceited exactly, but he just thought he was the greatest songwriter ever and that kind of bothered me.

It was when you left the group that that was it. You didn’t get any royalties after that. But that was fine. That was the agreement we had and I always felt that was perfectly fair. Staying with the group another year or two I might have made a lot of money, you know, but I didn’t.

It wasn’t acrimonious. I was kind of young at the time and what I recall was I just got tired and decided I wanted to go back and live in one place and all. I wrote them a letter that was accepted perfectly nicely and they got another cellist. I even helped them get the other cellist, so it might have been fairly friendly. I remember forgetting to sign the letter. I was like 22 years old, I didn’t know what I was doing. But it was not acrimonious.

Ron Palmer: Tim didn’t like a lot of things that were going on so he quit. As far as I know he’s still playing in Portland with the Oregon Symphony Orchestra. That’s what he did right after he left here.

Sandy Chapin: In the beginning when he was on the cross-country tour, he just took off. I mean he was traveling from state to state and moving across countries. Later when my kids were filling out college applications and they had to put down religion, they said ‘What am I?’ I felt a little badly because even though they had gone to church in Point Lookout, we had never joined a church in Huntington because I said our religion was “Go find Daddy.” I would pack them up at the end of the school week and we’d go to Rochester or we’d go to Philadelphia. We would go to where Harry was. Sometimes I had a babysitter and I went on the road. It varied according to their vacation time and schedules and so forth but I mean mostly it was my job to have a relatively stable home life and keep up the score and so forth.

###

Share your feedback with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.