At one time or another in your life you’ve sung some element of a Burt Bacharach song out loud.

With a virtual warehouse chock full of hit singles, the now 91-year-old composing legend has defined American popular music for more than five decades. From Dionne Warwick putting on her makeup and saying a little prayer, to “Alfie” pondering what it’s all about, to raindrops falling on B.J. Thomas’ head, Bacharach’s big band sensibilities and musically vulnerable stylings, to this day, speak to the everyman, the everywoman, and the everyone in between.

Yet while we are all easily familiar with Bacharach’s output from 1960 to 1970, the 1980s, and his resurgence in the 1990s thanks to unabashed fans like Mike Myers (i.e., Austin Powers) and Elvis Costello, his creative output of 1975 to 1979 is seemingly harder to recall.

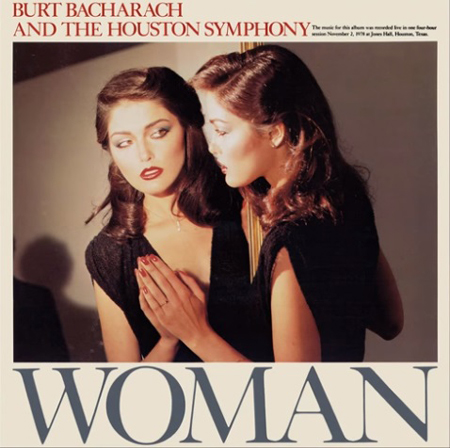

Ironically, this would be the period when his strongest album efforts would hit the public consciousness. This year marks 40 years since Bacharach released his landmark Woman album on the A&M label, a loose conceptual masterwork with seven tracks that outline traits of femininity — romance, passion, and fragility included.

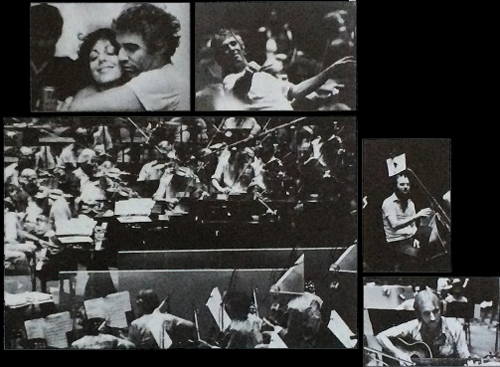

The landmark element of this album revolves around the fact it was done in collaboration with the Houston Symphony Orchestra. The largely live recording took place over the span of four hours at the famed Jones Hall in November 1978. Merging classical and jazz inspired orchestral players with Bacharach’s own top-grade studio instrumentalists and longtime female vocal trio, Woman would emphasize Bacharach’s musical maturity, capture Libby Titus (aka Mrs. Donald Fagen) at her most seductive, and remind listeners of Carly Simon’s viability when her touring presence was all but nil.

“(Woman) gave (Bacharach) an opportunity to use color and nuance in a way that’s different than what you do with a smaller ensemble and with a studio recording,” Paul Ellison, a former bassist with the Houston Symphony who played on the album, told me recently.

“The album means a tremendous amount to me personally because how many people get to write a lyric for Burt Bacharach?,” says Sally Stevens, a Bacharach backup vocalist for years who is only one of three featured soloists on Woman. “It’s a beautiful album.”

From the opening orchestral blasts of “Summer of 77,” you can immediately tell this is a Bacharach album through and through from its musical leanings: fast tempos, intertwined genres, and emotional brassy climaxes. It’s a classy work for tuxedo wearers but just as cool for the T-shirt and bellbottoms crowd. Forget the schmaltz of “Heartlight” and “Arthur’s Theme,” this is a Bacharach who isn’t afraid of the word primal.

Yet had it not been for symphony head Michael Woolcock, the project may never have happened, according to Ellison, now the Lynette S. Autrey Professor of Double Bass and Chair of Strings at Rice University’s Shepherd School of Music.

“Everybody was very positive about it from the beginning. It was a completely different kind of experience and we expected that,” he told me. “We were all symphony musicians, but I would say at that point the orchestra was on the young side and I don’t think there was anybody that was unaware of Burt Bacharach … Everybody thought, ‘Hey, that’s a great idea!’”

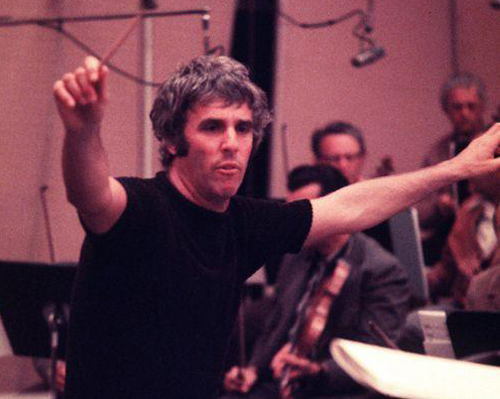

Ultimately, when Bacharach entered Jones Hall to kick off the recording session, it was class, respect, and professionalism all the way.

“He was very comfortable with us; therefore, we were very comfortable with him,” Ellison said. “He was a consummate professional. Everybody understood that he’d been in the studio standing in front of orchestras one way or another, whether he was on the sideline or actually on the box. He knew what he wanted, he knew what he had written, and he knew what he was hearing. He was very good at listening to the people that he brought. In a situation like this, it’s all about blending so that the mics pick up the right colors and still keeping the focus of where he wanted it to be. He was great at balancing that from the podium.”

“I knew all of the songs he was known for and that a lot of other artists had recorded the songs he wrote, but I wasn’t sure what to expect from the composer himself,” adds Warren Deck, a former Houston Symphony tubist who played on the album. “The man we saw was a consummate musician who had complete command of what he was hearing and what he wanted to hear. In addition, he was a killer piano player and knew how to run rehearsals and recording sessions where things got better and nobody got out of sorts about any of it.”

While it’s difficult to recreate the entire recording experience via this column, for vinyl owners of the album, just take a gander at the inner gatefold sleeve to see the gamut of Bacharach’s emotions – stoic, intense, euphoric. It doesn’t matter if this was an orchestra he hadn’t previously worked with. The synergies were clearly palpable.

“I would say he was responding honestly and that the whole experience was just that for him. He was inquisitive, he was probing, he was collegial, he was co-conspiring to get a particular kind of idea and therefore he had everybody with him,” Ellison said. “There were not people going in any other direction. Everybody was tuned into the same idea and he was a joy to work with. There was absolutely nothing but collegial feeling from beginning to end.”

Ellison adds the album’s collective cleanliness and efficiency can be further attributed to legendary jazz drummer Grady Tate, who kept time effortlessly all the way through its minimal stops and starts.

“We can thank Grady Tate for just about everything that’s on this album and the fact it all came together the way it did,” he said. “Had Grady not been there, I don’t know what would have happened. It wouldn’t have been the same experience by anybody by any means.”

Bacharach’s longtime lyrical partner Hal David is not in tow for this album, so the maestro compensates by having his music do his conveying for him. “Woman” is a softer, sweeter and all the while shyer piece while “New York Lady” takes on the bounce of the popular disco genre at the time.

“There is Time,” a vulnerable ode to what love could be, features Stevens singing at the top of her vocal register, trying to carry off the emotions of a woman afraid to face the inevitable but grateful for what she experiences in the present.

“We had written the piece together because originally he had conceived of possibly a whole album about ‘women’ but more like a journey or story,” she told me. “That kind of morphed into what we eventually did, songs with women lyricists. I had been writing with him specifically toward this album at that time.”

She adds: “For me it was a very personal lyric about a relationship. I won’t say any more than that.”

This would not be Bacharach’s first time literally playing around with the notion of a concept album. His prior effort, 1977’s Futures, reflects his sentiments about family, growing up, and the importance of interpersonal relationships. Tracks like “We Should Have Met Sooner,” “No One Remembers My Name,” and “I Took My Strength From You (I Had None)” are pretty self-explanatory based on their titles alone.

On Woman, Bacharach relies on two other female vocalists to help his concept come further alive. Libby Titus channels Maria Muldaur and Marlene Dietrich as she sultrily sings the track “Riverboat.” You can feel the sweat start pouring even before she purrs the lyric “95 in the shade.”

As Stevens recalled, Titus’ onstage execution only appeared easy.

“At that time Libby was very nervous about performing ‘live.’ Burt had specifically asked me to do whatever I could to support her and help her with her nerves. If she hadn’t been able to sing, I would have gotten to sing the song she wrote with Burt,” she told me. “So, of course, I had conflicted wishes going on at the time. But Libby had done some hypnotherapy to deal with the nervousness and fear. When the time came, she just leapt confidently up to the mic.”

Though the album depicts the ever-popular Carly Simon as being present in the moment with the orchestra to close out the album, both Stevens and Ellison could not confirm her presence at Jones Hall. Still, even with working her magic off-site “I Live in the Woods” is a strong album cut as the shy yet sultry artist channels the more chanteuse-like persona established on “You Belong to Me,” essentially coming out of her shell to lyrically revel in the attention of the men around her. All it takes is a lyric like “I live in the woods and I raise a child / I have no luck, but I do have style.” Though she frequently chants “Ooooh what a funny lady,” the song is meant to be nothing but serious as strings underscore its intensity.

Like the microcosmic moment in time that is this album, Stevens, Deck and Ellison summarize the experience as being both exciting as it happened, and eternal among their life’s accomplishments. That’s why it’s important Bacharach shouldn’t be defined by individual songs, but his sense of the album as art.

“It was a thrill for me. A few things happen in your life that you never just expect to have happen and they’re little treasures and you touch upon them and you go on and do more of what you do,” Stevens says. “That was one of those moments for me.”

Per Deck, now an adjunct professor at the Lamont School of Music at the University of Denver: “The project made a lasting impression on a younger kid, especially one whose training was in orchestral classical music. Seeing music made in a (slightly) different genre at a first-class level at close range was gratifying, educational and memorable. The commonality of doing something as well as one can regardless of the vehicle is something valuable I took away from that experience.”

Adds Ellison: “It’s the kind of thing that’s special enough that’s worth listening to why it’s special.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.