By Ira Kantor

Photos Courtesy Chapin Productions LLC

The life of Harry Chapin, charismatic musician and iconic humanitarian, was unexpectedly and tragically taken on July 16, 1981. He was 38 years old.

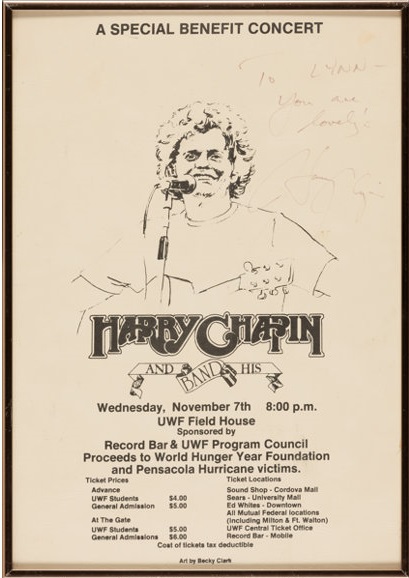

A human dynamo whose sheer tenacity landed him on the Billboard charts, on Broadway, in the White House, and at the forefront of the world hunger movement, Chapin lived by the mantra of “When in doubt, do something.” In following this mentality, Chapin’s 10-year solo career encompassed more than 2,000 concerts, nine studio albums, the creation of global nonprofit World Hunger Year (now WhyHunger) and the love and respect of fans, fellow musicians and key political influencers alike.

Hailed as a consummate musical storyteller, Chapin is best known for his character-driven tunes —“Taxi,” “Sniper,” “W-O-L-D,” “A Better Place to Be,” “30,000 Pounds of Bananas” and “Cat’s in the Cradle” included. Yet despite having only four Top 40 hits to his name, Chapin’s songs remain one of a kind — elevating him to the same artistic status as classic singer-songwriters of the era like James Taylor, Jim Croce, Gordon Lightfoot and John Denver.

Nearly 40 years after his death, the following 10-part oral history seeks to tell Harry Chapin’s story through the firsthand, on-the-record testimonies of the “characters” who knew him best – more than 50 family members, friends, business and political associates and musical contemporaries. For added context, Harry’s own voice, along with other relevant news articles and reviews during his lifetime, are included in italics.

While there are other individuals and events crucial to Harry’s tale who were unable to be interviewed or showcased for this series, this still seeks to provide a well-rounded retrospective of a man whose life, being, sense of accomplishment and legacy remain unsurpassed to this day.

***

Chapter VI

CHANGES

Fred Kewley (First manager): I think Harry was a good man. He dumped me as his manager and that was devastating to me…because it was my first artist, could have been my last, and was my only means of making things work. At the time I had no idea what kind of residual income I might have coming from it or what else might happen, I just didn’t. I had a partner who managed [Kris] Kristofferson and I managed Harry, and he and I together were starting to manage some other people. I had that going for me, which probably saved my bacon.

That was it. That was it, no more conversations.

Harry was my first one. I tell people that he and I put each other in business.

Ken Kragen (Second manager): The only time in my management career that I ever worked for anybody else was in the mid-Seventies. Probably about 1977 I was working for Jerry Weintraub, a very famous manager. He produced “Oceans Eleven,” a lot of other movies, but at the time he had John Denver, Neil Diamond — we used to call it the Four D’s. I remember Bob Dylan. In any event he decided to sign a “C,” which was Chapin. And he sent me to meet Harry in, of all places, Canada.

It’s seared in my memory because I arrived at the hotel and Harry was there in the lobby. I think he had already checked in and we went up, left my bags in the room after I checked in, and then went back out in the street. I found despite the fact that I was 6’2’’ and a pretty fast walker I couldn’t keep up with Harry. I almost had to run next to Harry. He was always in a hurry going to everything. My very first impression of Harry was, ‘Boy you’re going to have to run to keep up with this guy.’ It was true because he was just doing a hundred things at once — flying from one end of the country to the next and then back, and doing concerts and charity work and all kinds of stuff.

We got to be very friendly and worked together. Then I left that company not long afterwards, maybe a year later or less, and Harry decided to come with me.

Sandy Chapin (Wife): The person who really was the most helpful and most congenial was Ken Kragen because he understood Harry. He instituted the idea that after every concert Harry would sell materials and sign autographs and raise money so that — this is after he started World Hunger Year — every night he was working he could be making money.

Ken Kragen: It was a technique I had learned and done quite a bit — to get him to give — in his case, I think he gave all the money from his merchandising sales to charity. He would tell people as he was finishing a show, ‘Follow me out to the lobby. I’ll be out there as long as it takes. I’ll sign anything you buy, the proceeds all go to World Hunger Year,’ or one of the other charities that he was supporting. Then he’d just stay there. The fans were madly devoted to him and he made a memorable impression on all of them.

I had influence on how we raised money for charity. But I didn’t have the kind of stature that I gained in the mid-Eighties, you know, from “We Are The World” and “Hands Across America,” all the other projects I’ve done since. I was a mildly successful personal manager heading towards big success in the Eighties with huge clients who were dominating the record charts. But by the time I really got to have the kind of leverage that I could have in a kind of Washington presence which I had for a while, Harry was gone.

Sandy Chapin: We both read “Jonathan Livingston Seagull.” Harry used to talk about example and so I would use “Jonathan Livingston Seagull.” I said, ‘You can’t just go around telling people to fly, you have to bring them along.’ It was this whole existential conversation that we used to have.

Ken Kragen: He tended to say yes to everybody. It was a sort of Harry Chapin quality that if you needed him for something he was just that great guy. I mean we had to kind of almost prevent him from doing too much. He would just try to do every single event, every single thing that anybody ever asked.

He was on the go, in this rush, which I later came to feel had a lot to do with his thoughts that he wasn’t going to live past 33 or 34 at the latest.

***

Jen Chapin (Daughter): It’s not like he was partying. He just had too many things he wanted to do. He absolutely wanted to be there for his family but he absolutely wanted to make a difference in legislation. I have an image of there being an old-fashioned calendar with dates, concert dates and it would say like “Greek Theater, 5,000 people.” There would be a number associated with how many people were going to be there and the capacity of the hall.

It was absolutely for validation purposes. He wanted to be able to please people and he needed to know that he was pleasing people. It’s classic psychology. Any chance that he could get affirmation from people, from strangers, from the press — although I think he resigned himself to not getting respected in the press — but he would stay after every concert until the last person left, you know.

Howard Fields (Drummer): Nobody got fired. Only one of us quit.

Shelly Schultz (Booking Agent): ‘Stay out of a city,’ we’d say to him, you can’t go back there. You were there seven months ago.’ He says, ‘I got to go back there. I got to do this thing,’ so he suffered. We couldn’t go back there for two years afterwards just to keep a little distance. You overplay something and you become like furniture in a city, so those are the things he never understood that you couldn’t explain to him, and that he was not interested in. He never thought about those things.

Don Ruthig (Personal Assistant): We did a concert in Syracuse, New York, one time and I was doing the sound for that and I had family up there and we’re all sitting there waiting for Harry to show up. He came in about an hour late — it was some kind of screw up in transportation — he missed his flight or something like that. But here was an audience sitting there for an 8:00 show, it’s 9:00, and Harry is just arriving and within five minutes they were all loving him. Everything was forgiven.

So many performers would get up and they would do their shtick, deliver a good concert, deliver the music but didn’t really connect. Their banter between songs was stuff that you could tell was kind of scripted. Not Harry. He could just come off the top of his head and relate to the audience and make it all better.

I remember Hampton Beach, New Hampshire one time. He was like two hours late. He got into a cab in Boston and he told the guy he wanted to go to Hampton Beach and somehow or other he ended up circling Boston for like two hours before he finally got up there. He walked into this hall and he made it all better. It was just the way he could kind of meet people one-on-one within a crowd.

Howard Fields: We never did three month tours. We were always out on the road for 10 days and home for three weeks, out for two weeks and home for five days, out for seven days and home for three days. It was like that but the excitement was always there. You always wanted to do a good show and you always had a sense people were there for you. They are paying their hard-earned money to come hear these songs. So that was always there, that excitement and responsibility, but there was a certain monotony to it at a certain point.

Shelly Schultz: Everybody around Harry was fabulous. There was no stress around Harry other than Harry. Harry was stress but he didn’t give it to anybody.

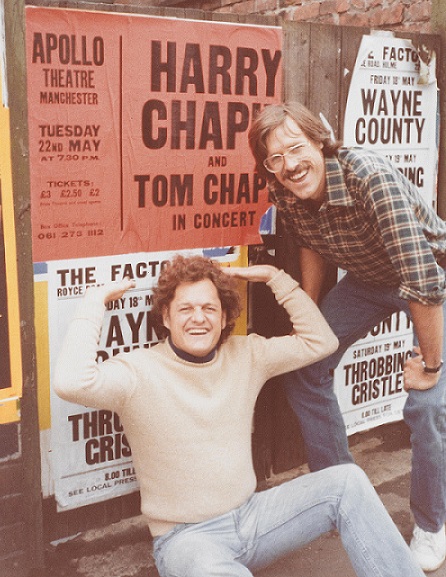

Tom Chapin (Brother): It was Bridgeport, Connecticut. I do a set and it’s not going over great, you know. It’s OK. Usually it went over fabulously. When it was wonderful it was a really nice thing, but the crowd was sort of a restive crowd. So I get off and Harry’s not there yet. I finish my set and I go off and the promoter is frantic, ‘No you got to go back out there.’ So I go back out and do three more songs and the audience is really shitty and I come off and I say, ‘What the fuck is he doing?’ Harry comes in all fired up, ‘How’s it going,’ and I grabbed him. I said, ‘You know what, I can’t fucking take this and I’m out of here,’ and I stormed off.

I got in the car and they go do the show and I drive about halfway back to New York. I pull off and call my wife — you know, no cell phones in those days — so I pull off and it’s a pay phone. I said, ‘Bonnie I did this and I quit…’ and she said, ‘You did what?’ And I’m sitting there talking to her and I said, ‘I’m blaming Harry for this. This is not Harry’s fault. This is my fault. I put myself in his place. I don’t need to be here. I’m not doing this anymore.’ She said, ‘What?’ ‘I’m going back.’ She said, ‘What?’ So I get back in the car and I turn around and I go back and I get back just before “Circle,” which is the way we end. I walk out and grab a guitar and Harry looks at me and off the mike he goes (whispers), ‘I love you.’ And then we sing “Circle,” and then we come back off and Harry’s out signing.

John Wallace goes, ‘Tom, ugh that was such a dramatic exit; you ruined your exit. What did you come back for?’ They were all laughing at me.

Then Harry came back and I said, ‘Harry, I can’t do this anymore. It’s driving me nuts. I’m just going to end up hating you and blaming you for this and so what I’m going to do is finish this tour another month and a half and then I’m going to just do my own thing.’ He said, ‘Really? Well I really want you out there.’ I said, ‘I know you do but I’m just telling you it’s not working for me and I want to not be blaming you, I love you.’ He totally got it. Anyway, we were always clear about it from then on which was great.

Big John Wallace (Bassist): The way I remember it (Tom) stayed about seven months and then he was gone. He’s always had more of a competitive issue with Harry, I think, than Steve. Steve’s relationship is different. Steve knows how good he is and the brothers know how good he is and how valuable he is and so he didn’t really compete with Harry where Tom did in a sense because he is more of a front-man. Not that there was any problems or anything, but I think that Tom just figured he was ready to go his own way.

Tom Chapin: It was hard to be in this orbit if you were a brother. Steve had a lot of trouble with that. And the band got angry at stuff. When I was doing the benefit stuff that was great, it worked out great. We did a couple of tours. Went to Europe together at one point with the whole family and he and I did all the air bases in Germany and France. It was really fun and I always had the chance to do my own stuff anyway.

Howard Fields: Tim Scott was the first cellist. When I joined the band, the second cellist was a fella named Michael Masters. Michael Masters left the band and we had an interim guy who didn’t work out. He was with us about six months and his replacement was Kim Scholes and when I think of the band, the five of us playing Frisbee and softball he was the guy, he was our cellist. The five of us — Steve Chapin, John Wallace, Doug Walker, Kim Scholes and myself — that was the band. Those were the golden days, the five of us together. But Kim succumbed to certain pressures that we were all feeling at a certain period in the life of the band and Harry’s career and he just didn’t want to do it anymore. So he took off.

Kim was the only one who quit. It was a moment of haste and in the middle of a concert, he just left the stage. That’s just something that occurs to me when we’re talking about the difficulties of getting along with him, but it was not just the difficulty of getting along with Harry as the difficulty of getting along with any employer. It’s kind of stressful in a pressurized situation having to be on the road for long periods of time, day after day and things aren’t going well. If they don’t go well over a period of time it’s just stressful. We all felt it but Kim just didn’t want it anymore.

Big John Wallace: In a very dramatic fashion [Kim quit] by slowly taking his keyboard stack and just pushing it forward until it just fell over. Then he walked off. Very dramatic. But that was the exception. I mean you can maybe be annoyed at each other or something every now and then just like anything else.

But there were never really any big fights. I mean Harry never got in a fight with anybody. He was always round shouldered and goal-oriented. He hated conflict and fighting and he would always try to straighten things out. He was very cerebral. Reason over emotion. Doug and I – like every six weeks we would have a fight, but it was nothing. Kim did have a problem but Kim had some problems in general — not just with Harry I mean.

Tim Scott was in for two years and then Mike Masters came in for at least three-and-a-half maybe. And then for nine months, Ron Evanuik. Ron came before Kim. Then Kim, and then the last one was Yvonne Cable.

I liked Ron. By the way he was a great bass player too. I mean he could play some Jaco Pastorius, the late great bass player. I mean I was amazed watching Ron Evanuik play a couple of those tunes note for note like “Portrait of Tracy,” which is all harmonics and stuff. He was real good. But as a cellist probably he wasn’t as strong, you know, and I think he just decided to go in another direction. Of course Kim was a high-level cellist.

Howard Fields: The reason that Kim quit was an example of an ongoing thing and it goes along the lines of a few things I’ve said already which is that Harry was committed to doing solo shows and benefits. He’d commit the band to doing benefits and we didn’t care that much about doing benefits. What we did care was doing quality concerts. That was our big picture and Harry’s big picture might have been, ‘We have to do this show, we have to get this money for this organization.’

Harry had us do a show out in Texas on Tuesday, so obviously a sound company can’t get there so you have to hire backline — the equipment, drums, keyboards, amplifiers. On this particular night Kim played a little keyboards on a couple of songs and the equipment he had was inferior, wasn’t working. I’m not telling you anything that wasn’t documented by saying that. He just kind of like pushed the keyboard onto the floor and left the stage and left the band that night. So that’s why it was Harry’s sometimes lack of vision about putting on a quality show, and his point was we got to do it; we got to get this money for this, whatever it was.

And we said, ‘Yeah, but what about putting on a good show? Wouldn’t it be better to do that?’ So that’s where the rub was. That’s a good example of some of the disagreements we had with him.

Big John Wallace: (Harry) was up front about it. Of course he did a zillion solo benefits. We averaged maybe 125 nights a year or something and he did, I would say, from ’75 on probably another 50 at least himself. But he asked us and we agreed to do 24 a year; two gigs a month for World Hunger Year. So we did that, and maybe some more, but I don’t think anybody ever resented it. It was a good cause and how can you resent somebody when the leader is the hardest working guy. What are you going to say? I mean he’s out there leading by example. He would never ask anybody to do more than he wouldn’t do.

Don Ruthig: It was kind of like herding cats a lot of the time. Yeah, he was very frenetic. I mean at that point I think he was doing something like 200 concerts a year. At least half of them were benefits. So he was all over the place, and then he got involved in all the lobbying efforts. So yeah, his schedule was nutso. As a matter of fact I used to keep the official airline guide, the OAG, by my bedside because I could expect at night after a concert. He’d call me and say, ‘How do I get from here to there?’ And usually he needed to be in Washington the next day to do some lobbying, or he needed to go someplace else. There was never a dull moment.

Sandy Chapin: I used to say to Harry, ‘Well, you made this choice, I didn’t.’

Howard Fields: It was pretty obvious to his inner circle — his band and his family — that that’s where his future was. I don’t know that he ever said anything, but it was pretty clear that he was using the Long Island community where he lived as a stepping stone into local politics and who knows where it would have went from there.

Sandy Chapin: He was always afraid that he wouldn’t be productive enough, so he would force himself into a vice. When he was raising money on Long Island, he would actually call a press conference and announce that he was going to do a fundraiser for the new Long Island Philharmonic and he was going to do it in Nassau Coliseum. He had no musicians, nothing lined up. He would set a date and then he would get on the phone and start to make it happen. He would force himself into the vice and announce something that no way was in place in order to force himself to have to pull it off.

Marie “Peachie” Marsden (Friend): ‘When in doubt, do something,’ he would always say. If you don’t know what to do next, just do something.

###

###

Share your feedback with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.