By Shawn Perry

The Grateful Dead, over ten years after their final performance, remain the quintessential psychedelic jam band. Aside from their innovative musical mix of rock, folk, bluegrass, blues, country, and jazz, the ever iconoclastic, unconventional Dead were pioneers on a variety of fronts: from allowing their fans to tape their shows to creating an extended family that included everyone from their close friends to their faithful road crew.

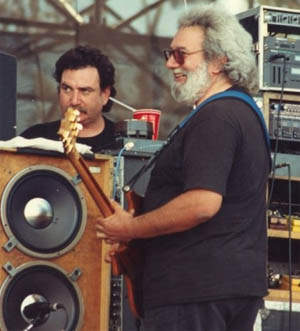

Steve Parish was a primary family member of the Grateful Dead for over 30 years. Stumbling onto the scene in 1969, he was absorbed into the band’s organization as a roadie, close friend and confidant. Anyone with a passing knowledge of the band knows the Dead’s road crew wielded an exceptional amount of power and influence. In so many ways, Parish, along with other sprite characters like Ramrod, Kid Cadelero, Rex Jackson, and Dan Healey, were as vital to the long and strange trip as the band members themselves. Parish not only handled Garcia’s gear; he was also manager of the Jerry Garcia Band. The tight bond between Garcia and Parish lasted right up until the very end, when on August 9, 1995, Jerry Garcia passed away. Parish was one of the last people to see Garcia alive.

Since then, Parish has written Home Before Daylight, a delightful book about his experiences with the Grateful Dead that’s heading to the big screen. He has also worked intermittingly with various members of the iconic band, as well as been involved with various Jerry Garcia posthumous releases. In addition, he has busied himself with a flurry of other activities, including hosting RoadieRadio.com, an online roundtable where Deadheads can get the inside scoop of life on the road, featuring interviews with band members and other key associates of the inner circle. In keeping with the cutting-edge tradition of the Grateful Dead, Parish told me he was reviving RoadieRadio.com as a podcast. The following interview took place in 2006.

I want to ask you about your book Home Before Daylight, which does an excellent job of chronicling your 30 years with the Grateful Dead. I’ve read other books about the Dead, such as A Long Strange Trip : The Inside History of the Grateful Dead by Dennis McNally and Rock Scully’s Living With the Dead: Twenty Years on the Bus With Garcia and the Grateful Dead, but yours had a personal touch I found appealing.

I didn’t want to delve into things that other people had written about. I stayed out of a lot things that other people had dealt with — the history, which Dennis dealt with in his book; paying back people, which Scully seemed like he was doing, trying to be put the knife in a couple of people — which I wasn’t out to do to. I wanted to talk about what it was like to be on the crew and what life was like in that world. It was such a unique crew experience; it was like no other band.

With most bands, the crew functions as hired help. But with the Dead, you guys were an integral part of band.

We were true brothers. It was a special thing about the band. Jerry’s imprint was on everybody — he was that kind of guy. He claimed we kind of invented ourselves in a way. We started working at a place called Alembic, building a PA. And the Grateful Dead took that PA over and that solidified it. Jerry really respected the people who worked for him. He was a guy who loved the working man — he was raised that way. So he said, “these people are helping us through life, let’s share this thing with them.” It really worked well. If we were sitting around and talking about where to go in the country, there were some really good, intelligent things that people had to say and we tried to make the right moves that way. Of course, if we got too far out of line, someone in the band would say, “Shut up, we’re doing it this way.” Or sometimes it would come down to somebody else saying, “Hey you know, you guys are right.” And that worked. There was mutual respect and it spread out to the whole family structure of the Grateful Dead. We were trying a sociological experiment in a lot of ways.

Do you think the way the whole organization was set up had something to do with the band’s long-running success?

Definitely. We put the audience first. We wanted to give them the best show we possibly could. That’s why we were always striving for such perfection in sound. We put in everything we had. We didn’t take anything out money-wise, the band or the crew, until later on when the band started doing well and they shared that with us. The whole thing was based on making the audience happy first.

Jerry’s thing about letting the audience tape — a lot of people in the band and crew thought that was crazy at the time. But we realized that was a good thing. We weren’t going to play the games with the record companies in those days. We were outside the norm. Now that model is the way the business works — letting your audience download your stuff is the way it has to be.

I always dug what Garcia said about taping: “Once we’re done with it, the audience can have it.”

Perfect. That’s where he was at. Since his demise, the Grateful Dead has slowly crumbled because he really helped to keep it together.

Are you still part of the Grateful Dead organization?

It’s not really an organization anymore. They each have their own bands. We’ll always be friends — we all live within close distance and keep in touch. But it’s pretty much dissolved. This only just happened recently. I worked for them up until a few months ago.

Were you involved with the Other Ones and the Dead?

I went out on some of those tours. I was out with Phil Lesh when he first started his band. But it just wasn’t the same. I was so close with Jerry; we worked hand-in-hand together. It just made me miss him more.

The road has changed a lot. The rules are very different. We had such a wild and free lifestyle back then. You can’t live that way and travel anymore. At my age, it isn’t that exciting. It’s still a beautiful thing. I constantly take from that experience and use it for what I’m doing now in my life.

In recent years, the doors to the Jerry Garcia vault have swung wide open. As Jerry’s closest friend, confidant, and manager, I would assume you’ve had a big hand in that.

John Cutler and I worked on the very first one that came out. We picked everything and were the producers of it. Since then, the estate has gone through changes of management. In the beginning, I was very close to all the people that were dealing with it. Then I stepped back because there was a lot of infighting between Jerry’s ex-wife and his daughters. It was horrible, fighting over all kinds of stuff. So I stepped back out of that because it was getting stressful. Chris Sabak was managing it until January and I was consulting with them. I still am at this point. It’s something I can’t disentangle myself from completely, but they have other people going through the tapes.

Some of the Pure Jerry Series CDs I’ve heard sound incredible.

That stuff is great. I was lucky because I probably saw Jerry play more than anyone. We had both bands. All the side projects I got to do with him were incredible. He could just go into a studio and play with anybody after hearing a song one time. That was a fantastic gift he had. So many people wanted him to just do a little bit on their albums, but he didn’t have the time unfortunately with the Grateful Dead, rehearsing two bands, having Old And In The Way, an acoustic band with David Grisman and other acoustic projects. There was a line of people who constantly wanted to play with him. It was a great career in that sense.

In your book’s forward, Bob Weir says Garcia made you his manager to get revenge on the music industry. It’s a little more complicated than that, right?

(Laughs) That’s Weir’s way of having some fun with me. The truth of the matter is that I stand over six-foot-four. A lot of people think that a big guy isn’t too bright — they put that handle on you. Jerry wanted to disapprove that theory. He put me in the position to do his thinking on how to move his band around. He trusted me explicitly because we had that bond.

But I could not let go of the equipment. I still came in and restrung the guitars and plugged Jerry in and kept that bond with him. Usually, anyone in management drops their roadie stuff and jumps into management. But I kept in both worlds. Weir knew I was a blue collar guy doing a lot of white collar guy stuff. Bobby loves to poke fun at authority, so it all made sense to him. He and I are very close, and he knows my mind. Really, managing Jerry was pretty easy. We had a lot of opportunities offered to us. It wasn’t like we had to go out and beg for gigs. So I learned at the feet of 10 other managers and Jerry knew I could handle it.

Much of your book talks about drugs — from you as a teenager being sent to Riker’s Island for selling acid to widespread drug use within the Grateful Dead organization. And yet, it sounds like you mainly stuck to the lighter stuff. It’s like you were a pillar of strength to counter all the madness.

The LSD and marijuana phase was a fun, lighter time. We were younger and happier. But then darker stuff like the cocaine and heroin moved into the scene. You could wake up in the Grateful Dead — no matter who you were — and you could drink a quart of Jack Daniels and you could drink a quart of vodka and you could do whatever you wanted, but if you didn’t do your job, it sucked. If a guy on the crew acted that way, we had to get rid of him. We couldn’t deal with it eventually.

Drugs like heroin and coke made some people not as honest as they were, so we lost that edge of innocence. I tried to fight against some of that, but it was very difficult. You couldn’t become a moralist because there you were in this world where everything went. It was very difficult in that way. I wasn’t crusading to try to stop it, but I tried my darndest to keep everyone healthy and on track.

You also talk extensively about friends, associates, and family members you lost. I literally had to set your book down and take a walk after reading about the tragic accident involving your first wife and children. How were you able to rise above the rigors of the rock and roll lifestyle and keep going?

With the Grateful Dead, we tapped into a higher spirituality. We really cared about people. That family kept me alive. When that particular thing happened with my family passing away in that car wreck, I couldn’t have done it without these guys. They literally came over and fed me and sat with me. For a band to do that for anybody is a beautiful thing. They all care about their people. This was brotherly love you can’t imagine. It saves you from destruction.

Bringing music to people — which was our real goal —– you could throw yourself into it and get over any tragedy because Jerry could play us out it. In other words, the music sustained us through it all. Jerry’s playing that night — I’ll never forget it. I can think about it right now. I remember being behind his amps and he was playing “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue.” It was an anthem to all our friends who were gone. Guys like Badger — whom I write about in my book — people said why write about a Hells Angel, but he was an amazing guy. He was like a living, breathing Viking who came to life with a heart of gold. He taught me things about life. He had visions of what we were all about. Those kinds of people who you met in this scene gave you inner strength. When they passed on, you were able to hold onto that strength. (Rex) Jackson was one of my best friends. When he died, I didn’t know if we’d be able to make it through another day. But his strength came through because he was bigger than life. He was an amazingly unique character. When he died, the band sat there, every one of us with tears in our eyes, and said, “Where are we gonna go now? It’s over pretty much.” But we kept going. We knew there was no way you ever stop.

We lose them all the time. Don Pearson (the head of Ultra Sound, which provided the Dead’s PA system from the later 70s through to the 90s) just passed away last week. We’re having a big memorial tomorrow at the Fillmore. We’ll just get together and have a wake for him. The Grateful Dead, that very name randomly picked by Jerry, became our lifeblood. A lot of times we were tasked with bringing dear friends to the grave and making sure it was done properly.

What do you miss most about being on the road with the Grateful Dead?

That energy, that excitement, that edge you don’t get in regular life. The show much go on and everything coming together at the last minute for that fantastic moment when it was action, lights and show. And we worked our asses off to get to that point each day. I don’t get challenged quite like that anymore, but of course I find the challenge of life never dull and I keep it that way.

Having seen the band 30 times, I know that everyone has a favorite show or era. How about you?

Any night was a great night. There are some that stand out. Europe 72 they played great every night because we were so inebriated on LSD (laughs). Jerry’s vibrancy would come alive, even in later days, and he had these amazing bursts of energy and that drove the night up. The one I wrote about in my book when we were at Hofheinz (Pavilion in Houston, Texas) and we wrecked the truck (November 1972). That was right after the Allman Brothers had lost their bass player (Berry Oakley). Jerry played that night for all our lives. I remember almost any night when I can sit and read the logs; I can remember moments when it was incredible.

I saw the Dead in Las Vegas several times. Those were always great shows.

We took Vegas in a roundabout way. We never went there for years because it wasn’t our kind of place and we knew it. Then we played the Aladdin Theater and had a great time there. We started becoming really popular at the Silver Bowl stadium gigs. Those gigs were really great. Some of the best we ever did.

Had Jerry survived, do you think the Grateful Dead would still be going?

I think we’d still have it going — maybe do a tour a year. Before Jerry died, we bought this huge facility in Marin County. There was some space in the back and we wanted to build a theater there. Without us having to travel, we would have the audience come to us. Jerry wanted to keep playing — he would have never stopped.

I remember when we were young and at one of the nightclubs in the city. We were sitting around in the afternoon, and I asked: “Are we going to keep doing this when we’re old?” And Jerry said, “Yeah, I’ll be on a street corner playing and you can pass the hat around.” He wasn’t going to quit no matter what.

Looking back, what’s your take on the whole Grateful Dead phenomenon?

It was a fantastic, rich, warm and moveable feast that never let up. To this day, I meet people all over who were very touched by it. I’m very proud to have been a part of it.