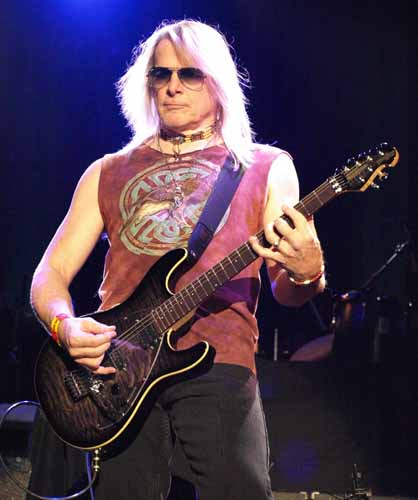

I’ve said it once and I’ll say it again: Steve Morse is one of the best guitar players in the world. And he’s been with Deep Purple, one of the best bands in the world, for 20 years. I thought it was a brilliant move when he signed on with Purple because they had run their course with Ritchie Blackmore — and the classic lineup of the early 70s wasn’t going to happen in the 90s or since then or likely ever again. So, in my opinion, Steve Morse helped save the band from extinction.

While they haven’t exactly set the world on fire with hit records, Deep Purple still maintains a heavy touring schedule, much of it taking place in Europe where their popularity is vast and varied. But, as Morse tells me here and as he’s told me before, the States are a different story. It might also have something to do with why the band has only recorded five albums since Morse joined (although that’s fairly commonplace with many of their peers as well).

I had heard rumblings about their 2013 release Now What?! in late 2012, and was overjoyed to learn that Bob Ezrin would be producing. If Deep Purple had another good record in them, he could make it happen. And he did. As I would tell Morse, Now What?! is the best thing he’s done with the band. Stagnant sales in the U.S. be damned — it holds up to pretty much anything else I’ve heard this year. For Morse, however, it isn’t enough.

In an interview I did with the guitarist in 2002, I called him the hardest working guitarist in show business, and that distinction has hardly changed. In addition to his Deep Purple duties, Morse continues to show up on various albums, collaborating with this singer or that producer; he’s even part of another band called Flying Colors. Their self-titled debut album rattled enough ear drums to create demand for a follow-up, something we touch on in the following conversation.

Which leaves the Steve Morse Band, something he returns to when time permits. As it is, that time is the last weekend of August and most of September for a short opening slot on tour with fellow shredder Joe Satriani. Knowing I would be attending their second show at the Orpheum Theatre in Los Angeles, I asked what, if anything, we could expect from his set. That along with everything and anything he’s doing in 2013 and beyond gets a full and thorough explanation.

~

So Deep Purple is on the festival circuit over in Europe this summer, is that right?

That’s right. In fact, we’re on stage in a couple hours at the Swedish Rock Festival.

They just love you guys over there at these festivals, don’t they? I mean, that’s your bread and butter.

Yeah, part of the culture here is that families and people go to them. They don’t necessarily have to be die-hard fans, “I have every album of this band.” They’ll just go because it’s a community activity and as a result, you can get huge crowds of people, you know, with any band that has any recognition with the public as being OK. It is different. They celebrate the summer more because there’s less of it, maybe.

I saw some footage from the Wacken Festival in Germany. You guys went over really well. I actually saw you play some of the new songs from Now What?!, which, in my opinion, is the best album you’ve done with Deep Purple. It truly defines the Steve Morse/Don Airey 2013 version of Deep Purple. What made this one so special? I know you really went out of your way to make this one something really unique.

I think a big change was having Bob Ezrin come in. I worked with him on the last Kansas album (In The Spirit Of Things) when I was in the group and he showed that he can make things happen, put things together with some real guidance. At that time, in Kansas, we really needed it and I felt like Deep Purple did too. We needed to change a few things about the way that we were recording. One of them being that just the whole sound of the band was, I think, a big improvement by putting the vocals and drums as part of the mix as opposed to right on top of the mix. It makes it more like a band to me.

Bob was absolutely phenomenal in terms of the pre-production. We had so many ideas and so many songs for this album that it really became, “What do we do? What do we choose from?” And Bob has a very colorful mind and he was able to keep track of about 20 different songs and their progress, and whether he liked the lyric direction or the melodic direction or whatever. As we worked on them, he would drop in on rehearsals and he would sometimes just sit in the corner and act like he wasn’t listening. And then all of a sudden you’d hear him yell out, “I’m not liking this” or “I love it.” Little comments like that, and then he would get intensely into it sometimes with us. Bottom line is, he was able to really be the bad guy in terms of no, this goes, this stays. And it saved us from having to go through that, and kind of arguing amongst ourselves. So there was an overabundance of things to choose from and he ultimately, as a producer, did what probably producers are supposed to do all the time and it probably gave it a little bit of direction too. The big thing that was different was we spent more time in pre-production and with a very intense producer who was really able to keep track of something.

I get the impression that he was able to tap the potential of the band, a potential that had not been tapped into before, really. That’s sort of what I’ve gotten from this record listening to it. He’s also involved in the songwriting as well. What was the process of that?

He would come in while we were working on the stuff and he would say, “No, no, no, no, we’ve gotta have more of this and less of that.” You know, mainly direction-wise, but it was specific enough direction and so much of it that everyone felt he should be included in the credits. I don’t know exactly lyrically, but I know musically he was making a lot of suggestions about, “Do this, do that, take that part out,” or “That’s too busy,” or “Morse, tone it down.”

You would all contribute to the mix before Bob would hear it, right? You’re all playing and he’s listening?

Yeah. For instance, on “Above and Beyond,” I kind of planned that out beforehand musically. I didn’t have any vocals. I just said, “Here’s what I think the vocals would be.” I actually prefer if I and the other band members don’t really bring in tunes. That one I just couldn’t stop working on until I got that finished because I actually thought we were doing that with horns and strings and stuff, like an orchestral little kind of prelude. I imagined that as a prelude to the album. And normally, what we do is like Ian Paice might start the day by just playing a beat. We jam along with it and noodle along for about 15 to 20 minutes, and out of that will come something. And we’ll take that. Don runs with it, I run with it — sometimes we run in different directions, but we always have ideas on the spot. What Ian Paice and Roger (Glover) often are doing is refereeing that. “No, no, no, I don’t know about that. I think you need to play, you’re getting off the track…” And Don and I are like, “Yeah, we can do this,” and “Yeah, but what about that and what about this?” And so, there’s always this kind of back and forth thing between a restraint and unbridled instrumental excess as, some people would refer to it.

At the bottom of this is the same roots we all have, which is the love for basic roots music. It’s an interesting blend, and Ian Gillan will kind of give a thumbs up or thumbs down based on gut instinct. Then he’ll just disappear and start working on lyrics. Then he’ll pop back in, get refreshed about the tune, and then walk away and write more lyrics. He’s kind of like an apparition — he’s there and he’s gone, he’s there and he’s gone. So yeah, we have a weird dynamic, but it works. And the bottom line is, everybody really appreciates that everybody’s involved. And it makes it something unique that we couldn’t do unless everyone was involved.

“Above and Beyond” is actually my favorite song on the album. The record has done, from what I understand, pretty well over in Europe. But, of course, over here in the States where half the people are tone deaf — they just don’t know a good record when they hear one — I guess that has something to do with you guys not planning any tours over here anytime soon. Is that about right?

The U.S. is a strange market for Purple. There are definitely hardcore fans and people that like the direction of the band, and do show up at the concerts. I sort of trace it back to the fact that the band was broken up or in splinter groups during the time that MTV was forming and sort of missed that boat of being stamped a big U.S.-approved classic rock band. Because of “Smoke on the Water” and “Highway Star” that influenced a lot of other bands, because of that, the band was in an underground realm. But on the whole surface of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame level of recognition, the band — because they’re not etched into the memory of people’s video consciousness — I think that has something to do with it.

And the fact that radio in America — with classic rock they pick one or two songs and just beat it to death — that’s it. They don’t want to hear (that) the band’s still together and doing new material together so much. The good thing is the Internet is — well the Internet is taking away a lot in terms of recording musicians being able to ever make a living just recording — but on the plus side, it does sort of open up a bigger underground communication that says this band is alive, this band is happening and people like them live. And that carries a lot of weight, and that’s starting to matter where we really could do more tour-wise in America. And that’s just simply a matter of finding the right act to pair it with. Like when we did the tour with Lynyrd Skynyrd, that was great; with the Scorpions, that was great; with Emerson, Lake & Palmer, that was great. And these kind of things that we have done in North America — they book so much that here we are going a year without seeing the U.S. Although I’m going to be playing in the U.S. in a matter of weeks with Joe Satriani doing a guitar tour.

That’s correct and that was my next question because I’m going to be at your show with Joe when you play at the Orpheum in LA. So you are going to be doing a short tour here with the Steve Morse band; that’s with Dave LaRue and Van Romaine, I assume. Is that correct?

Yes.

It’s been four years since Out Standing In Their Field. Are you going to do any new songs or pretty much cover your catalog? What can we expect from that?

Well, it’s going to be a short set, so I think we’re just going to try to get the most variety. And, you know, since we’re opening, there’s a weird dynamic there. Sometimes, the first song is what it takes as a trigger to get some people to walk in from the lobby, if they’re buying drinks or T-shirts or just hanging out and talking. So there’s weird considerations being an opener. And we haven’t really done that since, well —well, I take that back, we did the G3 tour, same kind of thing. Because of the G3, I’m used to the fact that a certain percentage of fans are not necessarily aware of our catalog so we’re just going for variety. Not necessarily high-energy; I don’t think any headliner likes to have the opening act beat the audience to death. So yeah, we’re just going for the whole musical variety approach, positive energy.

I won’t be in the lobby drinking a beer — I’ll be in there watching you. So you’ve got the Steve Morse Band, you’ve got Deep Purple and if all that wasn’t enough — you also have another little band called Flying Colors, who released a great record last year. And it’s just come across my radar that you have a new live DVD/Blu-ray coming out from your European tour. Do you have plans to follow that up with a new record, a tour … what’s going on with Flying Colors at this point?

Actually, we have already started the second studio album, but because of my schedule I really couldn’t do any more. We’ve got about half an hour’s worth of music already mapped out. There’s a lot of work to be done, but everybody’s full of great ideas. It’s one of the coolest writing experiences I’ve ever had. The guys are absolutely mighty. And Casey and Neal — I mean, they’ve done solo albums of their own from top to bottom, and, of course, (Mike) Portnoy’s one of the most prolific, quick-thinking musicians I’ve ever known. And Dave, he can like read my mind: “Here, let’s do it this way,” and he’s instantly there. It’s an amazing line-up. I do love working with them; it’s just the band got together and was formed during one of the busiest periods of my life where I had the least amount of spare time. I’m kind of bending over backwards to kind of do everything I can with them, but it is extremely busy. The album’s probably not going to be done for a while because of schedule only. But the energy is there, the vibe is really good with the band.

Cool, I’m really looking forward to hearing more Flying Colors. Getting back to Joe Satriani, I did interview him recently and we talked about how technically you replaced him in Deep Purple because he had been with the band for about a month or two before your arrival. I asked him if he had any regrets about leaving the band and he told me part of the reason he didn’t want to stick around was because he didn’t want to be that guy who had to live up to Ritchie Blackmore’s legacy. Was that ever an issue for you? When you came into this band, did you find the whole idea of living up to Blackmore’s legend a daunting task, or did you just say, “Screw it, I’m going to be who I am and see where the chips fall?”

I had a pretty good idea of the way this kind of thing works out because I did spend five years working with Kansas with Kerry Livgren not there, you know. They’re both icons in different ways, Kerry with Kansas and Ritchie with Deep Purple. The band impressed me, the fact they wanted somebody with their own personality who wasn’t going to be a clone of Ritchie. I thought that was a cool direction to go; it was very long-term thinking. The best short-term thing was to get somebody who looked, acted and played like Ritchie, and then people would say, “Well, alright that’s not Ritchie but he’s got all the same moves and he reminds me of Ritchie.”

The long-term thinking — it really impressed me — was that the band’s got to grow and you can’t replace somebody that’s very original, like Ritchie was. So instead of replacing him, just bring a new sort of direction. And I like it. I like the challenge because I was a big enough fan to love what he did, but also have done enough of my own stuff to where I’m fine putting my own spin on things from the past. And, of course, throwing in lots of ideas to the present. I knew that there was going to be a certain minority of people that are just going to hate me because I’m not him, and as time is going on, that percentage has shrank because they don’t come in contact. At first, it was cool for people to see on the Internet how much hate they could spew. One or two people could create a lot of damage, sort of like a pyromaniac experimenting with matches and gasoline. But those days have, for whatever reason, they’ve gotten less, and by and large, the only people who come are people that want to be there.

And I think because Ritchie set a good example with his fans by saying, “Hey, good luck new guy. I’m not going to tear you down.” Just “Good luck” and that was great. He really could have set me up badly if he wanted to because of his cult status, you know. But I think that has really helped. It gave me a chance to stand or fall on my own as far as what those people that — well you still see them at the shows, they’re wearing Rainbow shirts, Ritchie Blackmore shirts, and they’re right in front and they’re just glaring at you and stuff. But the one thing that’s different about me is that I actually understand those people. Because I think about it — if you went to see your favorite band, and you memorize it, every note of the record, just from listening to it so much, you’d love to see the original guy that did that guitar solo. OK, I understand that. But at the same time, it’s not possible. The band isn’t ever going to be that way again. It’s not because of me; it’s just because of the energy and the direction of the past. So, I actually don’t mind standing in front of those people and saying, “Hey, this is today. Get with it or let somebody up front that wants to. Let’s have a good time. Let the music change your mind.”

You mentioned the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which has sort of eluded Deep Purple for one reason or another. I spoke to Roger Glover the day after this year’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and I said, “You should have been there.” And you almost were, because I know you were on the short list. But do you care about that? I know the rest of the guys don’t really give it a whole lot of thought, and they kind of think it’s an American thing. What are your thoughts on it?

I think it would be odd if a band that was part of the roots of rock ‘n’ roll was in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, don’t you think? What’s the connection? A hard rock band, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? Is there any commonality there? No, no, I’m being sarcastic. It’s really weird. I do see enough of politics in so many facets of our lives that I know that things happen that don’t make any sense based on internal pressures that you can’t see. And just like somebody could be on our guest list for one of the shows and they could get treated like crap by security or somebody who works in the venue that has no love for music whatsoever and is no part of us, but they could associate that with oh, well, “Purple screwed us over and they didn’t have my name on the list.” There are a million examples of these kind of things that happen in our day-to-day lives.

We don’t know what they’re thinking, or what the other pressures are. And there may be sponsors involved, there may be people that are on committees that for some reason, the last thing they want to do is have a rock band in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Seriously, I know that things like that do happen. That when people steer some kind of organization seemingly away from the direction that they’re supposed to be, I don’t know. I honestly don’t understand, but it’s the way it is. Me personally, I don’t live or die over anything that has to do with recognition. The only recognition I want is from my kids and family and people that have seen me, stood right in front of me, watching me perform. Those are the ones that I’m concerned about. As far as mass adulation, it’s a double-edge sword. You pay a price. And that price could be the choices that you make, it could be the erosion of privacy, it could be making your decision-making flawed by thinking that you’re above an average human being. All those things — those are dangerous parts of I think … hoping for popularity too much.

I like the saying that if you take care of the music, the music will take care of you. And that’s the level of success that I want. I want people to think that I’m taking care of the music. The rest will follow at the pace it needs to or should be. Not everything is going to turn out fair or what you expect, but over the long run, personally I’ve had a very long career. I’ve been able to play music really as long as I want to. And same with the band Deep Purple. So success-wise, everybody’s had their success. There’s no question about it. And being recognized by, you know, an entity that, even though it has the name Rock and Roll in it, is, you know, that’s pretty superfluous to what the real issue is. I know the other guys feel very similar about this too.

People right in front of us tonight when we play, that’s the ones that we’re most concerned with. I’ve watched them, just to make a point, brush away certain pop success. I’ve seen it happen. Not because they hate success; it’s just that if there was one point that was being overlooked, that would be brought up and you know, sometimes that can derail your big shot. This is a band that doesn’t move or maneuver for big shots; I know that. For big shots at success I mean. And I think that’s the best recipe for longevity.