If you have any interest whatsoever in present-day rock ‘n’ roll, Rival Sons is the band to watch. So why are they being featured on Vintage Rock? Well, there are a few answers to that question, the first being that the band has a sound akin to many of the artists on this site. The second answer is that they’ve transcended that “old-school” approach with a “new-school” attitude. And the third answer is that I worked with the band when they first started, and even then, I sensed they were destined to become a Vintage Rock band (whether they like it or not). Watching their progress, I’ve come to recognize that rock ‘n’ roll, if it’s going to last, desperately needs the Rival Sons mojo. Four albums in — their latest Great Western Valkyrie came out in June (2014) — and this band is primed to take the world by storm.

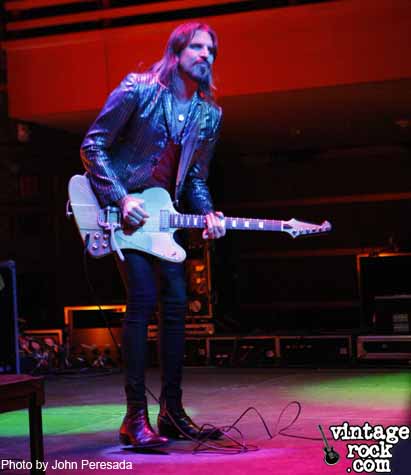

Case in point: When I did the following interview with guitarist Scott Holiday, he was getting ready to take the stage at New York City’s Gramercy Theatre for a sold-out show. According to one report following the show, a number of music business big-wigs were in attendance because there’s a lot of buzz around Rival Sons. Their broad appeal — everyone from young metalheads to old classic rockers loves them — their expanding popularity, especially in Europe and Canada — this is what has caught the suits’ attention. Rival Sons, who signed to Earache Records in 2010, could very well be in a position of maneuverability — both creatively and commercially — most only dream of. In a day and age when YouTube and American Idol has become the breeding ground for up-and-coming talent, Rival Sons’ whole modus operandi is a throwback to a kinder, gentler and more organic way to winning over the masses.

I hadn’t talk to Scott in a few years, so it was great to finally catch up and see he’s still the same hard-working musician from Long Beach with loads of ideas. The rest of the world is just now catching up to his creative energy. A Long Beach native myself, I recall seeing the band blossom as they played the circuit — three, four nights a week, from the Tiki Bar in Costa Mesa to the Viper Room in Hollywood. Real due-paying. One night before they started calling themselves Rival Sons, I saw them in a small cocktail lounge adjacent to a now defunct comedy club in Huntington Beach. There were only a handful of people watching. But on that small stage, they were killing it like it was Madison Square Garden. The only missing element at that point was singer Jay Buchanan, and once he joined, they became Rival Sons and started making records. Five years later, and they’re about to explode. At this point, you just have to believe that even when others are struggling to capture an audience, there’s a still a glimmer of hope that somebody, somewhere is going to break through and carry the torch to the next summit. As it looks right now, Rival Sons are bearing that torch.

~

How you doing Scott? It’s great to talk to you. It’s been a long time.

It has. I think this morning I read a piece that you wrote. I went, “Holy shit, I haven’t talked to Shawn forever.” Nice piece. Thank you for writing something nice about us. Check’s in the mail.

I’ll be looking for that check, man. First off, congratulations on your success and everything that’s come with it.

Thanks, man. Well, you know, from the very beginning, you kind of were there at the epicenter. It’s just been chipping away at the stone, dude; keeping it to the grindstone, as they say.

This new record, Great Western Valkyrie — just really a huge step forward. I’ve got all your records, and it just seems like you’ve been taking steps forward with each one. And this record is just a huge one in terms of songwriting, the sound and rock ‘n’ roll in general. You’re at the point now, you put that record on and two or three seconds in, you know it’s Rival Sons. That’s a true sign that you have arrived.

Well, thank you man. Yeah, I think that has been a goal. Obviously it should be a goal for any band to, A: To come up with the sound. Or I should say, A: To progress and move forward and make a better record, write better songs, make a record sound better. Nobody sounds should stay in that one frame. Even a band when you hear their debut — “Shit, man, sounds like these guys have been around forever.” Our debut was pretty damn good; Before The Fire was pretty great sounding, if I say so myself. I’m never putting it down. They did a great job. It’s not our first rodeo. I’m not a kid writing songs. Some of those songs are pretty damn realized on that record. That said, getting together with these other fellows, getting together with Jay, and keeping our heads down and really trying to make something better, I think every record did show progression.

I felt the progression from Pressure & Time to Head Down was an enormous leap forward for us as a band and really spread the wings out, because we stayed pretty economical on Pressure & Time on purpose. It was really restraining for them, what we wanted to do, so the leap forward really was like jumping off a cliff from Pressure & Time to Head Down — like really going instrumental to more songs to six-minute guitar solos, really covering a lot of ground on that record. This record, I really wanted to do something that was a natural progression. It should feel like a bigger step forward than even the other one. But really, it was almost more like an amalgamation of the two, where I wanted to have something that was quite economical and crafted the right way where it almost doesn’t have to be a rock ’n’ roll fan that can enjoy it. That was the idea with Pressure & Time. You don’t have to be a die-hard rock ’n’ roll person; it should just be good songs. It should be gratifying for a listener to hear the hook-turn. That feels good and for us to listen to it as well. At the same time, it should sound expansive; it should sound more like we were opening up areas at the same time. That was the goal with this record. Really, that’s a lot of semantics. Again, we’re just trying to make a better record and connect more, and be more honest and be more ourselves.

You set such a high bar with Head Down. Did you feel a lot of pressure in following that

up?

Not so much; not a lot of pressure, really, no. I felt that the statement was solid on Head Down. But at the same time, after touring it for nearly two years, because of the offset with the releases in different territories, we had to stay out a lot longer. We toured relentlessly on that record. By the time we got to the recording time, I knew there were things we could do better technically, things we wanted to do differently, the way we wanted the record to sound different, and things we wanted to say — it was just time to say different things. You know, this band doesn’t enter the studio going, “God, I hope we can do it. I hope we can beat that last record.” That’s just a real chickenshit way to enter a studio. This band enters the studio like, “Damn it, we wanted to make songs for a long time. Finally! Finally we’re going to get miked up. I’m sick of this shit. I’ve had enough of playing these other songs.” As much as I love them and I continue to play a bunch of them, that’s just how we feel. I’m ready to make some new songs; I want to play these songs. I’ve got a lot of new shit to say. I’ve got a new guitar. I want to make some new sounds.

When you’re out on the road, are you writing? Although I read one piece where you said you do it all in the studio.

That’s all we’ve ever done, five records in a row. Which is probably why we get so chomping and crazy when we get in, because we don’t write on the road. We haven’t marinated on 30 songs where we’re like, “Oh, that ones going to be great.” “Yeah, but maybe we should do that one.” “But wait until we get this one finished.” It’s never that bullshit backroom chatter. It’s really all about coming up with concept and idea and influence and direction, and it’s really fucking actually kind of heady and intellectual and individual for us before we step it, and then it’s a melee. So we write everything — I don’t share anything with anybody. I won’t write on my own, and not like, get in Pro Tools and engineer and make like five tracks and do drums. I used to do that, and I won’t do that anymore because it takes away all the creativity and the passing of the cup in the room with the members. It really makes shit stale and robs the moment. And we don’t do that for that reason. We come up with ideas and everyone passes that idea around really quickly, really frenetically, and then we capture it inside generally five takes from the moment of us discussing the arrangement and hearing it the first time. So all the records you’re hearing the same thing — some first takes, some second, some third, but never more than the fifth.

So, a song like “Electric Man,” which opens the album, you come in with a riff and Jay just says, “OK, I’ll throw some lyrics on that,” and boom, you have a song?

No, it’s not always me and Jay off the bat. That was my riff and kind of rhythmic idea that I came to the guys with. I showed them the thing and I had the guitar sound in my head, a guitar sound struck up, and Dave the producer came in, and we discussed another part — I played this other part quickly, just messing around very quickly in the studio. Inside of 10 minutes of playing the riff and having Miley play this beat, after I was talking about it and playing the beat on the guitar riff on a break like this (hums the riff), you know, like coming up with ideas very quickly. “That’s it. That’s all we need. That’s it, OK? That part and that part.” So at that point, we have that part. We should also have a bridge probably, on this so we have somewhere to go. And I want to put a solo in here so, a solo on the “B” section. And then we talk it, and we sit down and play it. Sometimes we’ll do that and catch it on the first one. Like that’s it; that’s fine. Sometimes we’ll do it a couple more. I think on “Electric Man” we probably did it three times. Jay didn’t write yet; we did it as a band, me and Michael and David Beste, our new bass player, and then went into the room and heard it and all kind of went, “This is good. This feels really good. Feels great. It’s a little quick. It’s a little fast.” So we recorded a take, we actually pitched it on tape so we could get the right tempo and then we left it. And then Jay took that — we gave him the version of that, and he went into the back of the room that we have and wrote some different versions of that song while we worked on another one.

So is it typical that you might come in with some ideas for sounds and then you kind of create a song around that?

Sure, I’m thinking about sound and stuff all year long. I’m getting different ideas and trying different pedals and different guitars and different tunings, and having certainly a sonic structure in my head and a sonic idea of what I’d like the record to sound like. I discussed that with Dave, and Dave also gets this idea going in his head. It’s just as inspiring and crucial as anything else. Just like the songs and the chemistry — we’ve been very blessed to have decent chemistry. It works really quick; it unfolds very quickly and we all become very inspired. There’s other times too where I’ll bring a riff and Jay — he’ll have a song. He’ll be sitting back there writing and come up with an idea…for instance, a song like “Rich And The Poor.” He was sitting on a Wurlitzer, writing on a Wurlitzer, so it’s not like he has a guitar back there, but he has these chord changes and these ideas, and he’ll come to us and says, “Come on, I want to show you this thing I’ve got. I’ve got it on the Wurly. I just wrote it two minutes ago and I think it’s gonna good.” I run back and hear it — “Yep, uh huh.” We’ll definitely react to something like that and I told him, “That’s fucking great. I already know exactly what the guitar is going to do in this — a very washed-out guitar, and clean reverb on the verses, very cinematic, this one. I’m excited. Let’s go record it right now.” And then we’ll run and go do it.

I was going to say, that particular song does have a very cinematic feel to it, as a lot of your songs do. Even when I first bumped into you guys so many years ago, I always loved the sounds you were getting out of your guitars and the diversity and the variety you were getting out of the music. I mean, you listen to something like, “Open My Eyes,” which is pretty straightforward and mainstream, but then you get to something like “Destination On Course,” which kind of starts off straightforward and then it kind of goes into this Pink Floyd moment, which I know you’ve done on some other songs, and I just love that.

Well thank you, man. Yeah, “Destination” was a very special one for me, because it’s something I don’t normally do. Since working with somebody like Jay, who’s not only my brother, but I feel a great amount of adoration just to work with such a great artist, he’s really one of the great writers around today. He’s fucking amazing. I don’t think anyone’s seen half of what he’s got yet. It’s gonna hurt people really hard when they do see it — that’s all I’ll tell you. And I’m really honored to work with someone like him. So I rarely will bring finished material that I’ve sung to and written lyric to, but this song was something that kept coming back to me and haunting me. Like I should share this, and I think Jay would sing this 5,000 times better than I ever could. I think it’s right for the band; I think it’s right for right now. So I had that song, except for the operatic sections, everything else I had. Even the ending was something I had written previously. I never shared with them until I brought this to the studio and shared with them on the acoustic guitar. Everybody went, “Yeah, let’s do that.” My version of singing was very much probably po’boy, or English, or something much more simple, but it was the same verses for the most part. And Jay took it and did this incredible vocal on it that’s much more akin for Nina Simone or something, like fucking jazz singing. It was really heart-wrenching to watch it go down. It was beautiful. So I’m quite proud of that one particularly.

It’s a great song. Now this is, of course, your first record with bassist Dave Beste. What effect has he had on the chemistry of the band?

Well, since we’re making everything in the moment, it’s really, you could say, four pieces of the pie — I’d have to say five pieces, with my producer Dave Cobb. But yeah, it’s a five-slice pie. If someone’s not pulling their weight, the record’s going to feel it; I think we could feel it. But Dave didn’t come up short; he pulled his weight very much. He was very present. He has a great energy. I couldn’t be happier with what we have in the group. I think he’s really right musically. I think he’s a little more fluid of a player. He has his whole set of influences that are different from mine or Michael’s or Jay’s or David’s or our old bass player’s (Robin Everhart). So there you go. He has his own flavor; I think it became more apparent on this record. The bass sounds different on this album. That’s the influence he had on it — that thing, the one thing, and how it moved and how it stuck. I think he did a real good job.

You mentioned Dave Cobb, who is just a big part of your sound and the whole group. Talk to me about your relationship with him. How deep does it go? When you guys get together, what comes out of that?

Dave is my friend. I’ve known Dave a long time now and we’ve all gone through a lot of stuff together. I’ve watched his career really start to flourish, as it should, because he’s a brilliant producer. He’s one of the great producers of our day right now. Just like I’m telling you I get to work with somebody like Jay Buchanan, it’s a great honor to work with somebody like Dave Cobb. He is really, really killing it right now. If you don’t believe that, check out that Nashville country scene that he’s turning upside down. He’s doing a good job. He’s really killing it. I found him, years ago, before we made Before The Fire, he was just kind of getting started in LA.

Did he work on the Black Summer Crush stuff with you?

Well, technically, that’s what we were — we changed the name. We entered the studio as that band and made Before The Fire with them. With that record, he was absolutely my foil for writing. Me and him basically bounced writing off of each other the most for that record. That’s mostly my lyrical melodic content with him involved on the other side, helping me write and do that, because at that point Thomas (Flowers) was working with us. He was great, but just wasn’t a writer for this band. He wasn’t a great writer for this type of music. It was a little more foreign to him. So I ended up working with Dave and then Thomas came in and sang on that stuff. And I just continued working with him. Even at that point — less then — but as we progressed, he became a little more integral with writing and arrangements. Dave’s a great bass player. Dave’s a great drummer. Dave’s a great guitar player; he’s got a great guitar collection, so he might throw a little guitar on and get in there with us if we’re having a problem and give us some ideas. He might start a song and just get the spark going with an instrument. A lot on Great Western Valkyrie, Dave sat on the drums and he would play and work out ideas, and me and him would play together, then Miley would come in and take over. He’s very much a band mate; he’s very much a brother — somebody who’s very integral in how this band sounds.

We’re all quite able to harness our vision. I produce at home, even now. And I did even before this band. Jay does the same thing. The other two are quite smart and have done plenty of studio work, and then they’re in the band. We could be producing these records, but technically we don’t because we shouldn’t. Because we have people like me and Jay in the group, we don’t know where that energy is going to go. We know where it goes with Dave, and it works very, very well.

As you said, Dave is a really hot producer. I actually reviewed another record he did, the California Breed record with Glenn Hughes and Jason Bonham. I don’t know if you’ve heard that record.

I haven’t heard it yet, but those guys are all pals. I’m actually glad you’re reminding me because Andrew (Watt, California Breed guitarist) just wrote me and I haven’t wrote him back yet.

I reviewed the record and I talked to Glenn about it. I actually saw their very first show at the Whisky. The minute you hear it, you can hear the influences of Rival Sons, which is kind of a funny thing. You’re influencing other people, dude (laughs).

That’s weird. Fucking Glenn Hughes, my God. He’s a pretty legendary fellow and a friend. He’s been quite vocal about it. He’s a sweet guy. I really like Glenn a lot. He’s really cool. And Jason —I haven’t hung with Jason, but he’s sent us messages and then we talked: “That’s fucking cool.” “That’s really cool too.” Like I said, I haven’t hung with Andrew or spoke with him, but he just wrote me the other day and I owe him a call or a message. I’m going to actually do it when we get off the phone, now that you’ve reminded me so I don’t look like a big asshole. It’s interesting how that all went down. We know that it came — supposedly — it came from one Mr. James Patrick Page. He spoke to Jason and said, “Oh, you’re going in to make this new record. First you should listen to this Rival Sons stuff, if you don’t know who they are, and then you should go to their producer Dave Cobb. You’ll want him to produce your record. This is amazing.” I guess Jason picked up our records and told us that he almost drove off the road listening to them. He was so excited he almost drove his car off the road. Actually he ended up making that record — you’re allowed to print this but it might get him in trouble — he actually ended up making that record on a drum set that was Miley’s that we left at Dave’s. We always work with Dave and we leave shit with him. It’s all good. We worked with him when we were there a couple of days ago.

In my review of Great Western Valkyrie, I mention that because of bands like Rival Sons, the term “classic rock” has been transformed from a musical era into a music genre. And I read in another interview that you’re not too fond of that term “classic rock”.

I think it’s less about me being fond of it and just the validity of it. They try to throw terms on bands. It’s like, go find a group of bands and they’ll say, “Why would you do that? Why would you call what I’m doing …?” Like I’m sure, most notably, the most recent time, is grunge. All those bands are so different. You’ve got Alice in Chains, Nirvana, Pearl Jam — you could not find a group of less-alike bands. They clumped them all together and called them all “grunge.” And they were probably all thinking, “What in the fuck are you guys talking about? Why are you even clumping us together? That’s ridiculous thing, just because we’re friends from the same area. We’re playing really different shit.” Anyway, this sort of reminds me because people keep asking me, “Oh I heard you’re not happy about this being called ‘classic rock’.” But that’s just ridiculous. Because “classic” is indicative of old, like “classic cars”. I’m not going to go buy a 2015 Corvette and go, “Man, that’s a ‘classic’ Corvette. That’s a classic car.” I guess people would say that though, maybe, now that I’m saying it. Maybe, I don’t know. It doesn’t seem to work with rock ’n’ roll the same. And it seems lame, because “classic rock” is like our heroes. Because we have some traits and sounds like those heroes, we are them? We are that? I don’t know. We aren’t that. We are rock ’n’ roll though. That is what it is.

You’re totally rock ‘n’ roll. The bottom line is that you and Jack White and Led Zeppelin all have albums in the Billboard 200 right now, in an age where albums are dying, you’re keeping it alive, man.

Well, God bless it. I can only thank the fans for that. Everybody wants to put the term, put the phrase, like we’re going to, “Save rock ’n’ roll — you’re the saviors of rock ’n’ roll. Are you going to save it?” Fuck no. I don’t want that responsibility. I’m just going to play it. Why don’t you all buy it and you guys will save it. I’m just going to play it though.

I want to ask you about your touring schedule. You guys just play out so much. You played some gigs in Europe with Aerosmith and now you’re in the midst of touring here in the States and Canada, and then back over the pond to Europe, where you’re a pretty big deal.

We have a big fan base there. They got the jump on the States. Even Canada has the jump, you know. But we’re looking to do things right over here and wake people up to it. All we can do is keep playing and telling more people, and people like yourself are putting stuff out and preaching the good word. We did about three weeks in Europe and we did television and festivals and headline shows, and then jumped over here. Now we’ll do some festivals, a bunch of mostly headline stuff, a lot of press, and then we go home for a couple weeks and come back out to Scandinavia and do all festivals, I think, maybe a couple headliners. We do really well in Scandinavia. The kids don’t know about this shit, but Sweden, Norway, Finland, Switzerland — kids, you want to be going in this area. Their knowledge is a lot further than ours, the economy is really stable and it’s a beautiful country with beautiful people. You want to go there. Thank God we’re doing good there. So we’re going to go back there and then we come back.

What’s the difference between playing for a European audience like that and coming here to the States?

I don’t know, I haven’t played to the same kind of audiences that I do there, because we’re a lot bigger there. But not much, really, not much. The biggest ones we’ve played to here are — they’re rock ‘n’ roll audiences. We’re seeing them at a Rival Sons show. I think we’re blessed with some really great fans. It’s as different as all the different people are in different lands are, and how different they could possibly be to each other. A strange thing happens when you get them all in one room, all kind of unifying over this one feeling, and all kind of coming together on our rock ‘n’ roll. When that happens, it becomes a paramount feeling, all these wonderful souls communicating and working together and thinking the same thing at the same moment. It becomes this really magical, far-out thing. It’s this really far-out thing to watch people kind of converge and have some harmony and some unification through music. So it’s hard to notice all the differences.

That said, if we wanted to get into cultural different things about being in each country, it could go on for a lot longer than this interview. At the shows, which is where I’m seeing most of them, it’s really similar. It’s great people. We just finished Detroit a couple nights ago, and I’ll tell you what. They have some fucking crazy rock ’n’ roll fans in Detroit. Every time we come through, they come strong. We just about sell or do sell out the building. They break drinking records, they buy all the merch we have, and they really make themselves known. So that place is very deep in my heart. I always look forward to coming back to Pontiac, Detroit, that area for sure. That’s some rock ’n’ roll people out there.

Have you been to Japan, South America or Australia yet?

We haven’t done Australia or South America, and our set this year is very, very hard. But we have done Sudan and we need to go back because that’s some great people out there, too.

And what about California? When are you coming back here?

We’ve got a slew of dates set up in September, I think. We’re just stringing them all together. Are you kidding me? I love my state. I love my home. I love that whole area, that West Coast — Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Oregon. It’s so beautiful. We have the most beautiful country, too. You get to see so many different things on that leg of the tour — deserts and forests, and it’s so beautiful. I’ve got so many friends and family that way. No one’s dying for it more than us. We have a whole bunch of stuff set up.