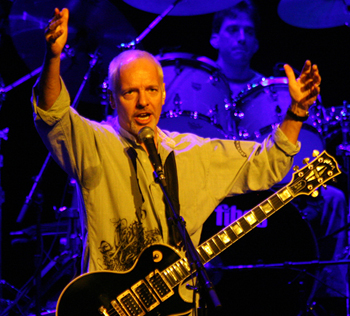

Peter Frampton is the perfect example of how a wildly successful young rock star can weather not one but two explosions of fame and come out of it alive, with sanity intact and as a far better musician and human being. To his four children, Peter Frampton is simply a father that provided them with a good solid upbringing while leaving home every now and then to play his music. To generations of rock music lovers, Frampton will forever be known as the pretty boy blonde, guitar-wielding God who sold a jillion copies of Frampton Comes Alive.

Now, at 57, Peter’s flowing blonde mane has since given way to a closely cropped head of gray. With three grown children and an eleven-year-old daughter at home, Frampton is comfortable with his role in life as a revered rock star, former teen idol (twice), and doting Dad who helps his little girl with her homework. Peter recently took time during the tour in support of his Grammy-winning Fingerprints album to talk to Vintage Rock about his early love of music, his famous music friends, and the gear that helps him compose the Frampton sound.

Peter, I’d like to ask about your earliest memories of music, maybe something that sticks out in your mind?

When my parents realized that I was into music — that I really had something special — I was about three or four, and there was a piano being played on TV. We were watching this classical music piano recital, and I said, “There’s something wrong with the piano.” My mother and father said, “No there’s not. Shush, listen.” So at the end of the performance, this guy comes out and says, “We’d like to apologize to everyone for the performance. Someone left a piece of music on the strings.” I was aware of musical sounds pretty adeptly early on.

What was your first instrument?

My first was a banjolele, a banjo-shaped ukulele. It was left in the attic by my grandmother. She made the comment that “one day, Peter might want to fiddle around with it.” I found it one day while retrieving suitcases for summer vacation. I asked my Dad what it was, and that’s where it all started. He showed me a few chords and a couple of simple songs, and that was the start of my affair with strings.

Did you take lessons or were you self-taught, and what would you recommend to a young kid that wants to learn to teach themselves or take lessons?

I think beginner players should definitely take lessons. I did, after picking up the basics by ear. I had no clue of rudimentary technique. My parents saw it was becoming an early obsession for me and thought it would be a good idea if I went to lessons. It was classical guitar lessons, and I took them for four years. That taught me how to read music with the guitar, and taught me how to learn the technique for string fingering with the right fingers on the right strings. Fingering the guitar the right way is a big help because it can wear you out trying to do it the wrong way. There’s always a quick way — or slightly easier way — to learn. You don’t want to make it more difficult than it is already.

Tell me about your childhood friendship with David Bowie. Could you see a music star in him at that young age?

Yeah. When I was first aware of him, I was 10 or 11 and he was playing at the local high schools on the weekends and for various affairs in the summer…local things like that. He was playing saxophone and singing. When I went to the school that he attended (which is also where my father taught) of course I made a beeline for Dave. We became friends then, and George Underwood (who was in my father’s class) — he was good friends with Dave and is to this day. George was an artist and did amazing illustrations. He ended up doing three of David’s album covers, including Ziggy Stardust. It was quite amazing with the three of us at lunch time sitting in the stairwell’s stone steps leading up to the art block (art rooms) with our guitars and using the stairway as an echo chamber while we played Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran songs.

What was life like for you between the Little Ravens and forming the Herd? Were you a good student?

I don’t think I was a very good student because I was always thinking about guitars and drawing them, or tracing them out of magazines. It was a total obsession. I was a junkie for a guitar as soon as I had one in my hands for five minutes. School was always secondary for me, unfortunately. I guess if I’d paid more attention…well, I’m not a dummy obviously. I just realize that as I’m helping my eleven-year-old do her math homework now, I did retain quite a bit. Once she reaches 13, I think that’ll be it, and I won’t be able to help her anymore.

I hope it doesn’t bother you when I say this, but I’m probably the only classic rock fan in the world that has never owned a copy of Frampton Comes Alive. What do you like most about that time in your life, and what do you remember as being the worst part of that time in your life?

You probably didn’t need to own it because it was always on the radio! From an exhilaration and adrenalin point of view playing in front of 120,000 people in JFK Stadium in Philadelphia…that’s pretty thrilling. It was surreal too to have that many people in front of me, shouting and clapping and all that. For every touring musician, the actual travel is a pain in the ass. The mundane stuff with being stuck in the middle of nowhere with nowhere to go or anything and just there for a show. That stuff…we get paid for the 22 hours a day when we’re not on stage. The two hours a day when we’re on stage — that’s the pay-off. That’s the free part, and the enjoyment. I’m just glad I had a band around me then and to this day that I could trust, and a good team behind me. We were definitely a force to be reckoned with at that time.

I interviewed Sam Andrew from Big Brother & The Holding Company a while back, and we were talking about Janis Joplin and stardom, and he made the comment that “fame is a total albatross.” Once the notoriety and popularity subsided somewhat, did you feel pressure to top Alive, or match it in sales or content? Were you happy (in a weird way) to not stay that huge and to go back to smaller venues, or were you resentful of the roller coaster ride of fame?

There’s a sort of odd approach to the career when you’re in that mode and sort of thinking, “Oh, well, what should I do now?” Instead of just doing it, you’re trying to plan what to do. I learned the lesson that you can’t chase your own tail. Yes, I’m honored and thrilled and it’s fantastic that Frampton Comes Alive was part of my career, but it was only one part. It’s past, and the last thing you want to do is live on the coattails of your own old success. I didn’t reinvent myself. I just went back to what I enjoy most…playing live and playing a lot live, and playing guitar. That’s what I’ve been doing since taking a little time off in the 1980s. I haven’t stopped since. With the notoriety of the Grammy for my current album, it’s the first thing that has absolutely nothing to do with Frampton Comes Alive. It’s like I have a new career. It’s not actually that, so much. It’s just a new fresh aspect of my career.

You’ve certainly got a lot of friends in music. I’d like to ask about your friendship with Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones…

Bill is like my older brother, and we’ve been like family ever since I got to know him when I was 14. He sort of took me under his wing and saw I was a pretty good player for a young upstart, which is what he called me. I got to meet him through being in this band called the Preachers when I was 14. They were a semi-pro outfit and played weekends. The drummer was friends with Bill, and he produced an album for us. I ended up being on TV that year — 1964 — with the Preachers, and we were with the Rolling Stones. He really elevated my career early on. He definitely brought my name out locally by giving us the album and everything.

Is it true you were almost in the Stones after Mick Taylor left? What happened there, and are you happy with the path your life took you on?

The day I heard it was a possibility to join the band, and being on the shortlist, I almost crashed my car. I heard it on the radio, like everybody else. I don’t know if I could have weathered the storm of the Stones. I’d probably be dead. I would have loved to have done it. I asked Mick after they got Ronnie and said, “Was I really on the shortlist?” and he said, “Of course you were.” He said he could see what was happening with my career, and Mick says they knew my career was about to take off. They have a perfect choice in Ronnie Wood. Keith and Ronnie are like two peas in a pod.

With the music you and Steve Marriott were working on before his passing, how did you two come back together to write and record? What were the plans for the music?

There were actually three songs I completed after his death. Obviously I would have liked to have finished them with him. We were going to do the one record and follow with a tour. He decided to go back to England to take a bit of a break in the middle of working, and unfortunately the accident happened and he never came back. I have to say, it was so phenomenal to actually sit down, just the two of us again to write, especially on the song “I Won’t Let You Down.” I’m very proud of that song, and it was so exciting to sing with him on that song. He was one of the world’s greatest singers… just phenomenal.

What do you most remember about your work with George Harrison on All Things Must Pass?

I was on five or six acoustic tracks, I believe, on the album. George called me down to the studio and asked if I’d do some over-dubbing. Phil Spector was producing and wanted more acoustics. He always doubled up on everything — that big wall of sound. So it was just George Harrison and me sitting on two stools in the Sergeant Pepper studio at Abbey Road, looking at the glass and Phil Spector and working on the tracks. In between takes, we’d start jamming, and that was the most enjoyable part of the whole process.

Can you tell me what prompted you to move from England to the U.S.? What do you like most about living in the States?

I moved in 1975 to New York. My girlfriend then was living in New York, and my management and everybody was there too. With Humble Pie, most of our work had been done in the States, so it seemed like for my solo career, it would be a good move to go and be available to work on records and be available for shows. I’m so used to living here now and I can’t think of not living here. People in America are extremely lucky. Most of them don’t realize how easy it is to get things done in this country compared to other countries in the world. I sometimes think we don’t appreciate America. You have to go somewhere else and see that things are not as easy elsewhere. People should really respect where we live here. We’re very lucky.

What are your kids’ ages, and did they grow up knowing who their dad was?

My son is 19, and my two daughters are 24 each. My eleven year old, Mia, is still living with us. The others have all flown the coup and are working on college and seeking their fortunes. Stuff like when I was on The Simpsons and Family Guy — that’s when Dad really got cool.

What is it about your black Gibson Les Paul that you love so much? How did it come about for you to release a signature model with Gibson?

The original black Les Paul that I had was when I was playing with Humble Pie supporting the Grateful Dead in San Francisco back in ’70 or so. I had swapped a Gibson SG for a Gibson 335, a semi-acoustic. With the loud levels we used to play, when I turned it up for solos, the sound was just all over the place, whistling feedback, you know. There was someone at the concert that heard the problem, and he offered to let me borrow his Les Paul for the next show. I told him I’d never had luck with a Les Paul and that I preferred SG’s. He brought it ’round to the coffee shop the following day, and it was this 1954 Les Paul. I played it that night. He had re-routed it for three pickups instead of two and it was recently refinished by Gibson. It looked brand new. I don’t think my feet touched the ground the whole evening. It was just such an amazing guitar. I came off stage and told him thank you, and asked if he’d ever want to sell it, and thanks so much. He said he didn’t want to sell it to me, but he offered to give it to me. He gave it to me. Mark Mariana is his name. We keep in touch even today. Unfortunately in 1980, we had a disastrous plane crash with all our gear on it in Caracas, Venezuela. The pilot and co-pilot were lost, and their loss was very tough. Their lives meant so much more than that guitar. I’m not saying I don’t miss it, but it was a piece of wood compared to their lives.

Cut all the way forward. When I moved to Nashville about 13 years ago, I used to go hang out at Gibson. It was like my club, and I’d go hang out with the luthiers. I made a lot of friends at Gibson. Mike McGuire, the head of the custom shop, suggested one day that they should make a Peter Frampton model. We spent a year working together on trying to make it as much like the original as we could. I tried to give him as much information as I could from what it felt like, and they came so close. I love my guitar. It’s probably nothing like the other one, but I love what they did for me. We’re over 500 made now, and the PF Custom is out there and the collectors love it.

Besides the Les Paul, what are some other favorite guitars you record and tour with — electric and acoustic?

Most recently, right before I did the jazzy sounds on Fingerprints, I found a 1959 Gibson 175, which is the single sharp cutaway jazz box, basically. It’s one of my favorite electrics all-around. I have two Gibson SG’s. They’re both 1962 models. One was to replace the one I got rid of when I got the Les Paul in 1970. Somehow, I got hooked up with John Nady of Nady Wireless, and he tells me, “You know I’ve got your old SG?” and I exclaimed, “You do?” So, guess who’s got it now? I’ve got the original guitar I played with Humble Pie back. I’m very partial to anything that’s still in existence now because I lost the ’54. I’m really in search of all the one’s I’ve played over the years. As far as acoustic guitars, Martin has made me an acoustic guitar to replace one I lost long ago.

Here’s the story… I had a Martin D45 when I left Humble Pie, and I recorded the Frampton’s Camel album with that. “Lines On My Face” and all those acoustic songs on there. We went on tour right after that in ’73 I think, that’s when unfortunately between one gig in Toledo, Ohio to somewhere else, someone stole that Martin. It left me with a very bad taste in my mouth and I was never able to bring myself to get another Martin. A while back, I ran into Dick from Martin Guitars at one of the NAMM shows. I told him the story, and he said, “We have to put that right, you should have a Martin. How about we call it The Frampton’s Camel Edition.” He made it to my specifications, and it’s an amazing guitar. They made 76 of those, I think. One other acoustic I love is the Tacoma Chief. I have one that was made before Fender bought them. George Gruhn in Nashville talked me into getting one and I still play it. I used the Tacoma for the Fingerprints record and it worked out great.

I’d like to know how you got introduced to the talk box effect — what was it like the first time you played through one?

It was introduced to me on by record by Stevie Wonder, the first person I actually heard using one on a record. It was made by Kustom and was called The Bag. I’d heard the sound before, where radio stations did their call letter promos on air with that sort of weird effect. That was the predecessor to the Talk Box, some sort of neck resonator. When I heard Stevie doing that, I was doing the session for George Harrison, and Pete Drake (pedal steel player) came in from Nashville, pulled out this box with a clear pipe, and plugged all sorts of things in. His pedal steel guitar started talking to me, and singing. I said, “Oh my God. There it is. I need one of those!” And he said, “Well, you can’t have this one.” Bob Heil of Heil Sound was making them. He’d made one for Joe Walsh for “Rocky Mountain Way.” I believe I have the first one or two production models, and it’s traveling around to Hard Rock Cafes and other places lately.

I’m betting you were never comfortable with the label of teen idol, both as a member of the Herd and after superstardom in 1976. How did you cope with the “teen idol” fame, and do you think it negatively affected your reputation as one of the generation’s best guitarists?

The first time it happened with the Herd, it was real exciting for about three weeks. And then it was causing problems within the band because I was not the front person in that band. I was the third singer – the backup singer. I think I sang maybe two songs in the shows. It came to a point where I realized that it didn’t matter if I played my guitar or not. The audience just wanted to look at me rather than listen to me play. It’s a lovely compliment, but it gets old very early. There are certain things that happen that are out of your control. You can’t help it if a picture – one picture – can change the perception of someone’s career if it’s the wrong picture. A musician’s career can last a lifetime. A teenybopper’s career can last about 18 months. That’s the truth. I am the old sage – the Wiseman – of this now. I’ve been through it twice, and it can be a career killer. Billy Squire… that same thing happened to him. Great singer, great guitarist… lost his credibility totally because of one bad video. I on the other hand have many things like that… anybody remember the Sgt. Pepper movie?? (laughs) But you live and learn.