By Shawn Perry

When music fans think of Ten Years After, they’re liable to picture guitarist/vocalist Alvin Lee, fingers a-flying across the fret board of his beloved Big Red, a Gibson 335 adorned with an assortment of peace sign stickers. The lock-and-loaded rhythmical drive pumped out by organist Chick Churchill, drummer Ric Lee and bassist Leo Lyons was certainly nothing to sneeze at; but it was Alvin Lee, whose name would eventually precede the group’s moniker, who became the poster boy and visual point man for Ten Years After.

Which may leave you wondering: How on earth can Ten Years After expect to carry on without Alvin Lee? Simple, they bring in a young gun, cut a solid record, and tour like madmen. After almost three years, the dividends are starting to pay off for Lyons, Lee, Churchill and new recruit, guitarist Joe Gooch. To keep the momentum flowing, Fuel 2000 recently released Now, the band’s 2004 studio CD, in America, while Roadworks, a brand new double live album, makes the rounds in Europe.

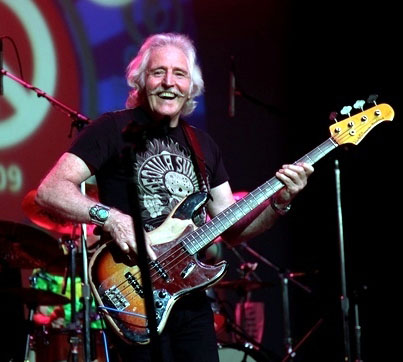

To bring me up to scruff on the Ten Years After front, Leo Lyons called from his home in Nashville, where’s he been living and working for the past nine years. We discussed the past, present and future of Ten Years After, as well as his production and songwriting outside the band. Almost forty years later, Lyons’ passion and commitment to Ten Years After is stronger than ever.

Let’s talk about the new live album Roadworks. It’s featured on the Ten Years After Now web site, and you can buy it in Europe. Any plans to release it in the States?

There will be, yes. It could be next year because our Now CD has just been released in the States. America is about a year behind.

I’ve only heard bits and pieces of Roadworks and it sounded pretty tight. Can you tell me how you went about putting it together?

We recorded it over two nights. Mostly we used one night with maybe a couple of tracks from another night. It was recorded during our European tour last winter. If I recall correctly, and I ought to because I mixed it and put it together (laughs), it’s mostly from Germany with a couple of tracks from France.

How did you go about choosing the songs? Were they all part of your regular set?

Yes, they are very representative of our regular set. Our regular set is really a combination of the old hits and the new material – based on feedback from fans. Fans, obviously, want to hear some of the old songs pretty much as I would if I was a longtime fan of a band. If I went to see Queen, I wouldn’t want to hear a new album and then nothing else.

We’ve added all the songs that people request. We try and change the set around as much as possible. There are always certain songs…like “I’m Going Home” always has to be in because people want to hear that. We try to play as much new stuff as possible. A lot of our fans in Europe now know the new material. You can judge that by seeing people singing along. The set gets longer and longer as we try to change it around and appeal to everyone (laughs).

The present incarnation of the band has been together for almost three years?

Yes, about three years I think.

Why isn’t Alvin Lee part of this line-up?

If you go back to when the band really finished in 1975, which is 30 years ago, that was the point when Alvin really didn’t want to work with us anymore. So it’s not surprising he isn’t with us now. Four years ago, one of our record companies re-released the catalog and Ric Lee approached Alvin about doing some gigs with us. But he said, “No, I’m not really interested.” And you know – it’s his choice. The difference between Alvin and the other three original members is that Alvin carried on. I took some time off. I think if I had carried on for another 30 years, playing “I’m Going Home,” I probably wouldn’t have wanted to do it either (laughs).

Are you still friendly with Alvin?

I haven’t spoken to him in about three years. I guess his idea was, “I don’t want to do it and I don’t think anyone else should do it either.” So, how he feels about it, I have no idea. And to be honest, I don’t care.

Didn’t he just make a record in Nashville?

Yes, he did.

But he didn’t drop in for a visit?

Actually he did, but I wasn’t here. I’ve e-mailed him since. We’ve always had a difference of opinion. That’s why the band finished in 1975. If you have a brother — I don’t know if you do or not — sometimes you get on, sometimes you don’t. With Alvin and I, that’s always been the situation.

How have the hardcore Ten Years After fans been receiving you?

We have a lot of young people coming to our shows in Europe. They don’t know who Alvin Lee is and they didn’t know who Ten Years After were until they saw us, so it isn’t a problem. There’s probably a few people who were at Woodstock, but you know I’d rather think about the future instead of the past.

I understand your son Tom was the connection to your guitarist Joe Gooch. Was there any hesitation having him step into Alvin Lee’s shoes and assuming the frontline position for Ten Years After?

There was some hesitation on my part because I said to Tom, “I think we really need someone with more experience.” Tom said to me, which put me in my place, “If no one gives him a chance, how’s he going to get experience?” I told him to ask Joe to send a tape to Ric Lee the drummer and let Ric have a listen to it and that’s how it came about. And quite honestly, we were all blown away. We’re extremely lucky to have Joe.

He’s not really stepping into Alvin Lee’s shoes because the band became Alvin Lee and Ten Years After way back in 75. Now we have a new guitar player. There are certain riffs that were written by Alvin that have to be played – parts of “Love Like A Man” and the ongoing “Home” intro, but after that Joe puts his own interpretation on things.

So you’re essentially creating a new identity for Ten Years After?

I think we’re representing Ten Years After 2005. The thing I didn’t want to do was to get another guitar player in and go out as a tribute band to ourselves. And we’ve made sure we haven’t done that. This isn’t the first time. When Alvin quit the band in 75, our own record label told us to get another guitar player and go out. But we didn’t.

What’s different about the band that used to play “50,000 Miles Beneath My Brain” and the one that currently plays “A Hundred Miles High”?

Obviously, I think we’re better, but that’s up to the fans to decide. It’s different. We play “50,000 Miles Beneath My Brain” as well sometimes.

Looking back at the success of the original band, is there anything you wished you would or could have done differently?

I don’t think there’s any point in looking back because everything’s a learning process. Hopefully I’ve learned something. I think I’m a better player now. I guess if I had to think of something that maybe I wish I had done was in 1975 when Ten Years After was finished, I thought I was too old to go on the road and join another band. And look at me now. That’s just the perception, isn’t it? Your perception based on what other people think. “Oh no, it’s a young man’s game” blah, blah, blah. We’re off on the road doing it because we want to and we enjoy it. Not because it’s a good way of making some more money.

Ten Years After has always been revered as a premiere live band and The Live At The Fillmore East CD released in 2001 is testament to that. Do you have any more tapes in the vault being prepared for release?

Not that we know of. But you never can tell.

How did you come upon the Fillmore East tapes?

Ric went into to do some liner notes on some different records when they were re-released, and that’s when they discovered these tapes. I remember recording them and in actual fact we had the live version of “Love Like A Man” on the studio single that came out in the U.K. And that’s how it happened, the usual synchronicity. I had a quick look on e-bay this morning and there were maybe 20 bootleg releases out there, DVDs and albums, live here, live there, even stuff going back a few months. So who knows?

Are there any concerts you know of that were filmed and could eventually come out on DVD?

There’s the Texas Pop Festival. I’ve seen a few cuts from that. And there’s the peace tour, you know the one on the train? We weren’t on the train, but we played in Toronto on that package.

You mean the Festival Express with the Grateful Dead and the Band?

Yeah, maybe they didn’t film Ten Years After, I don’t know. I’ve seen the DVD, but there’s no Ten Years After. Bill Graham filmed just about every gig that anyone played at the Fillmore West. I’ve seen a few bootleg copies of Ten Years After sets there, so that’s a possibility too.

What can you tell me about your production work that took off after Ten Years After broke up in 1975?

That came out of frustration, really. I was putting a hundred percent into Ten Years After and getting about five percent out. So I started working with other bands.

So you became a studio manager for Chrysalis?

I did, yes.

And you produced records with UFO, Richard and Linda Thompson, and Procol Harum?

Yeah, but a lot that really came before I was studio manager. It was because I had done a few records for the label. They bought two studios, Wessex Studios and AIR Studios. I guess it was around 74.

Musically, did you get anything out of producing some of these acts? Like UFO, they’re a lot different than Ten Years After. Any highlights from those sessions?

I was pleased that we were able to get the band going and give them some chart success. I kind of enjoyed it. Production to me has always been a second choice career to playing, but as I said before, I felt I was too old to continue to go on the road. But it’s a great buzz in the studio when the song is right, the playing is right, the sound is right and it all comes together like magic.

As far as UFO, you pretty much produced the cream of the crop – Phenomenon, Force It and No Heavy Petting…

The interesting thing was that when we were doing it, the record company wasn’t really that much into the band. It was a real struggle to get studio time. But we did. I think Force It was the first to chart in the States and it took the record company by surprise.

You’re also a prolific songwriter, with a hand on every tune on the Now album.

I came to Nashville nine years ago as a staff songwriter. I’ve always written, but, how can I put it, Alvin couldn’t relate to other people’s songs, he said.

He pretty dominated the songwriting in Ten Years After.

He realized from an early age that there’s money in songwriting (laughs).

Are you still a staff songwriter?

I lost my job when I started not turning up at the office (laughs).

I’d like to throw out the names of a few places and events pivotal in your career and have you fill in the blanks. Let’s start with the Star Club in Hamburg where you and Alvin Lee played with the Jaybirds. You followed up the Beatles, did you know them?

Not before we went there, but afterwards. It was the first time we ever left the U.K. as a band. It was six nights a week, playing an hour on, an hour off. It certainly knocked the band into shape and formed the nucleus of what we would do in the future. Taking songs, extending them, jamming. It was very formative. We went to Germany as a little local band and came back a little more seasoned.

So after Germany, you went back home. Which was where?

In those days, if you wanted to make it in the music business, you had to move to London. We did that twice, three times, starved and moved back home again. We were known in the Midlands where we came from, but not known in London. So we lived in London, but when we needed to work, we went back up north to pick up work again. The Beatles and all those Liverpool bands changed that eventually.

When did you take up the residency at the Marquee?

That was a year down the line from moving to London, We got a job working in a west-end theater playing the part of musicians in a play. That was a regular job. We did that for the short run. That was when Ric Lee joined us. To stay in London, we started working as a backing band for a pop group called the Ivey League and I started doing sessions.

I read that you once turned down Jimi Hendrix for a jam session.

That’s a figment of Alvin’s imagination.

So did you jam with him?

I knew Jimi because I met him when he first came to London and he asked me if I’d be interested in joining his band. So that sort of blows Alvin story out of the wind. I didn’t, of course. Jimi came to see us in New York. You have to remember we had played with him six or seven times prior to that, so we all knew who Jimi was. Jimi was left-handed and he really wanted to get up and jam. So he asked me if he could play bass. So Jimi got up and played bass with the band. I had to sit out. He turned the bass upside down and played it.

When you first came to America, did you play at both Fillmore East and West?

Our manager got a telegram from Bill Graham saying, “I just listened to the first album and I really like it. If the band is coming to the States, I’d like to book them at my venue Fillmore West. I’m opening up the Fillmore East and I’d like to book them there too.” On the basis of that, we went to America for six weeks with a few gaps in between but the two major venues we played were the Fillmore East in New York City and the Fillmore West in San Francisco. I think we did the Whisky and a week in Huntington Beach (the Golden Bear). We played this theater-in-the-round in Phoenix with the Grateful Dead and the Boston Tea Party in Boston. That was six weeks. The big breakthrough for us really was the Fillmore East. WNEW picked up on the band and it all went from there.

Do you remember any of the bands you were playing with?

We played with just about everyone from that era – Ike and Tina Turner, Buddy Guy, BB King, Zeppelin, Grateful Dead, Chicago.

How did you end up playing the Newport Jazz Festival with Miles Davis?

On the Undead album, we did “Woodchoppers Ball” and “I May Be Wrong.” The press found it interesting that a rock band was playing Woody Herman and Big Joe Williams. That’s how we were offered the gig. I think Newport was trying to open up to a new audience.

From there you played Woodstock. “I’m Going Home” was, of course, a highlight of the festival and a big part of the movie. What do you remember about that day?

The long journey there, no food, the storm, working it out, not getting out to the place, not having a hotel. That’s what sticks in your mind. Obviously, it was a great event. It’s sometimes hard to differentiate between the movie and the event after all these years. That whole era was absolutely fantastic. People were into music. America, more so than other countries in Europe, had it. It was a movement, a political belief, an idealism, the way you dressed, what you listened to, free love, drugs, the whole package. And you were either one of us or one of them. There was no commercial for it until the movie came out and everything in the music business changed.

How so?

Corporate people took an interest in it and saw that it was big business. You could start manufacturing things, you could promote things. IBM wanted to support tours.

How would you contrast your experience at Woodstock with the 1970 Isle of Wight? Was that a good gig for you?

I thought it was a good gig. There’s been a lot of negative press. I think there was probably this movement in France at the time where everything musical had to be free and a lot of people forced their way and busted down the fences at the Isle of Wight. You tend to read a lot about that. To play it, it was more sedated; it wasn’t raining, it wasn’t a mud disaster. That was pretty enjoyable too.

You must remember that when we played Woodstock and left, I didn’t think anything about that festival, none of us did until we came back on a subsequent tour. By that time the press had really built it into something and people were asking us about Woodstock. When the movie came out, it became even more. To this day, it does represent, particular for younger people, an era in music where they really feel they would have liked to have been. If we hadn’t done Woodstock, I wouldn’t be talking to you now.

Are you tapped into the music scene in Nashville?

It’s primarily the country music business here. There are a lot of musicians here. They’re kind of split into two groups: there are the session musicians and the road musicians. And very often, the two don’t meet. And then there are the writers. So there are three groups. And there’s an alternative scene going on where you do get a little bit of mixing. There’s a good blues scene here too.

So you find the city inspiring?

Absolutely. From a writing point of view and a playing point of view. Some of the best musicians in the world live or pass through here. It’s stimulating.

What’s on the horizon for Ten Years After?

We just finished a tour of France. Next week, we start touring again, through Holland and roam through Christmas, Germany, the Czech Republic, Denmark, throughout Europe.

Any plans to tour the States?

Definitely, yes. We’d like to come in and do some festivals so people can see what we look like and what we sound like.

What about another studio album?

There will be one, but the important thing now is to put the DVD footage we’ve got together and bring out a DVD. That’s what all our fans are asking for. We still have some more filming to do. The way music is going, people want to see something visual with the record. I get five e-mails a week asking when the new DVD is coming out.

Leo, why Ten Years After 38 years later? Do they fit into the today’s musical landscape? Do they need to?

We talked about Woodstock and I think there’s a tremendous interest in that era and the music of that era. I get a lot of e-mails from young people that are taking up guitar or bass asking if I can write up tabs to “I’m Going Home.” So there’s an interest in the music. We’re not mainstream. You can maybe put us in a blues thing, although we’re not strictly blues. With Ten Years After, it’s always been that way. It wasn’t quite heavy metal, wasn’t quite blues, wasn’t quite jazz, maybe a little bit more of a Chuck Berry, rock and roll kind of feel. I don’t think we’ve ever been in a bag.

When Ten Years After got back together, I produced the studio album Now. The difficulty for me was thinking what direction do we go in. And I started listening to the old records. We never really had a definite direction. We’d do a country song, then an old jazz song, then a rock and roll song, and then go off on a tangent and change it half way through. It never went down the rails in one fixed way. So I thought all we can try and do is capture the energy and enthusiasm that we had way back in 1969. And that’s what we’re trying to do.