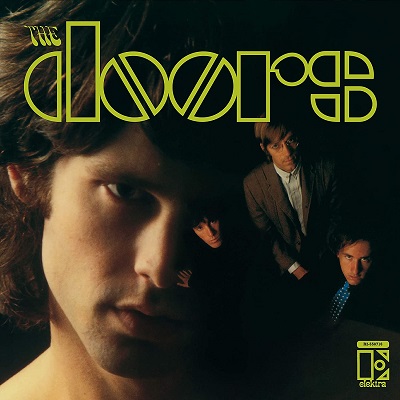

As debut albums go, The Doors packed a punch that still reverberates to this very day. Jim Morrison was young and hungry, ready to take a big bite out of the world. At this juncture, Ray Manzarek, Robbie Krieger and John Densmore would have followed Morrison anywhere. It was a path fraught with chaos, counterpoint to everything sunny and free. It was about living on the edge; about taking, as the great poet said, the road to excess leading to the palace of wisdom. An incorrigible baritone waxing death while a funeral organ leads the procession, a guitar unfolds like a set of massive peacock wings as the drums slam and samba — none of it remotely representative of the spirit the hippies were plugging into. In retrospect, it seems rather sardonic that the music of the Doors is a big part of the 60s landscape.

The first, self-titled album was the culmination of everything the Doors had been working toward since their tumultuous days on the Sunset Strip. It was fairly easy for producer Paul Rothchild to capture the band’s drama and impact from all four members — something that became increasingly difficult on subsequent recordings. Immediately out of the gate is the Lizard King’s anthem, “Break On Through (To The Other Side).” Inspired by the writings of William Blake and Aldous Huxley, the idea of breaking through to the other side (and what do we break through? What else but the doors…) was a life affirming concept that Morrison based his whole existence on. But it was with Krieger’s song, “Light My Fire,” that the Doors, as a large-scale rock and roll band, based their whole existence on. The second single after “Break On Through,” “Light My Fire” would be their first number one, trailing the Doors for the rest of their days. It would become a classic sketch in time for a group that was just about to mount a bucking bronco.

To further appreciate The Doors, you have to dig deep into songs like the bodacious “Twentieth Century Fox,” the ominous “Crystal Ship,” the ragtag, hard drinkin’ “Alabama Song,” and the creepy “End Of The Night.” Others like “Soul Kitchen,” a tune about a restaurant in Venice, or Willie Dixon’s “Back Door Man” simply add another the dimension to the band’s arsenal. And then there’s the pseudo-psycho dramatization affectionately known as “The End.” This last number, of course, is responsible for getting Morrison tossed out of the Whisky — its Oedipal overtones just a tad too much over the top — even during the swingin’ 60s. It was the kind of brutal honesty — a confessional blast of reality — that no one could ignore. All of which made the Doors — as a musical force, an exercise in veracity, existential theater of the absurd — one of the most fascinating acts of popular music.

~ Shawn Perry