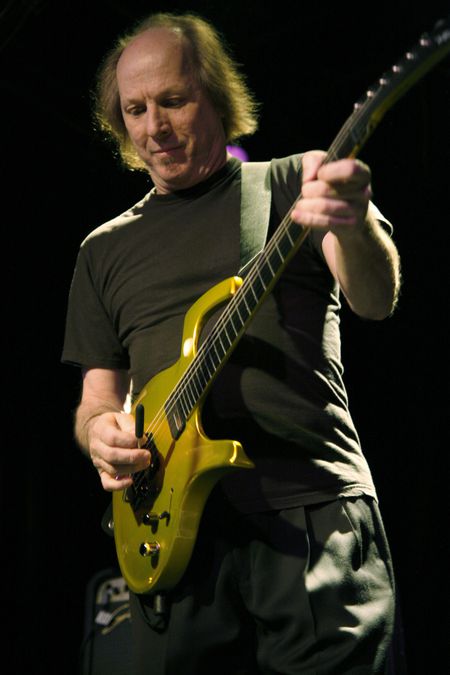

Adrian Belew Caught By The Tail

By Shawn Perry

It’s a sunny Saturday afternoon and I’m scheduled to meet with Adrian Belew at his Beverly Hills hotel. Just as I enter the lobby I immediately catch him in the corner of my eye — looking dapper, almost resplendent in cotton khakis and a light-colored pullover, along with his hair in a mild state of disarray. Belew is chatting it up with Robert Fripp, the de facto leader of King Crimson, who flashes me his iniquitous, demure smile and hightails it out of the lobby before I can get any closer. I would expect nothing less. Once I announce who I am, I’m told that things are running a little behind. Can I come back later, around a half-hour or so? Not a problem. Before I leave, Adrian says: “You know there used to be a Haagen-Daz right across the street. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to stay here. But they closed it. If it were still open, you could wait there.” Right off the bat, I see the attention to detail, the unmistakable thought process he must pour into his music. I can be thankful that Adrian Belew is looking out for me.

An hour later, I sit down with the man and I know I’m in for a treat. Adrian Belew has covered a lot of ground in his 25 years as a musician. Jumping in head first with none other than Frank Zappa, Belew went on to log time with David Bowie and Talking Heads before he ran into Fripp and reactivated King Crimson. Since then, it’s been one long, crazy journey. The guy even played on Paul Simon’s Graceland, for crying out loud. As passionate of a musician as you could possibly be, Belew maintains a wild pace that’s well-matched with his desire to experiment and tinker with ideas, concepts and meanderings of any sort — sitting in here, playing on that session, painting, writing, recording — and being the front man for King Crimson, one of the most eclectic group of musicians to ever roam the earth. It’s a full time job and Belew is particularly good at it.

The first portion of our conversation focuses on the new Crimson album, The Power To Believe, their first full-length effort in over two years. According to Belew, that’s roughly the amount of time the group always needs to complete an album. “It’s weeks to make a King Crimson record,” he says. “It’s maybe two years to write one.” It was a process of “writing it, rewriting it, refining it, redefining it” before the band even stepped inside a studio.

Like much of Crimson’s music, the key to The Power To Believe is an unspoken sense of balance, a benevolent bow to loose interpretation and a degree of improvisation based largely on syncopated chord structures and nifty little surprises around every corner. “The Power To Believe” is a four-part cycle that surrounds six other songs. Belew says it all came together in the final stages. “After two years of work, we knew we had all the major pieces. But only at the end of the record did we realize there was still something missing that could thread this all together.”

Within the thematic framework are some truly amazing moments between the four present members of King Crimson: Belew, Fripp, Trey Gunn and Pat Mastelotto. As a second outing by this particular combination, it’s been an adjustment to say the least, especially for Belew who had felt a strong kinship with Tony Levin and Bill Bruford with whom he had been in the band with since 1981. Without much explanation, the two disappeared from the Crimson fold after 1999’s Projeckts, a four disc box set of improvisational music played by various combinations (Fripp called them “fractals”) of the six member, mid 90s line-up. This fractalisation of King Crimson led to 2000’s The ConstruKction Of Light, which was met with some confusion by Crimson’s loyal followers and casual fans, alike. For one, the absence of Levin and Bruford altered the make-up of the band’s unique chemistry. But as Belew sees it, internal differences between Fripp and Bruford had been brewing for a while and a change had to be made.

“Even though I love being around both Robert and Bill, I’m glad to see that tension gone. Sometimes a tension can drive something, but I felt like that part of it was gone and now there was just tension,” he laughs. “It’s just two guys who don’t really see music in the same way and probably shouldn’t be working together. I’m sure they’re still good friends, but it’s a relief to me that I’m not stuck between the two of them. I respect them so much that I felt a lot of times I was in between these two guys who had their gloves on. And I was taking a lot of the punches.”

If anything, The Power To Believe shows how the group — as it always has in the face of continual shifts in personnel — has forged ahead and made the appropriate adjustments. This is especially evident now that Gunn and Mastelotto have begun to come into their own, demonstrating the sort of diligence to the Crimson cause that Belew admits was lacking. “I consider them the next-generation of King Crimson,” he muses. “It’s been intriguing to watch them follow in the footsteps and take over for Tony and Bill. I know it’s been very difficult for them because they admire those guys. But they’re different from Tony and Bill. They bring a younger and more adventurous mentality to the group. Pat is really involved in listening to all the hip-hop, loop music and all the stuff that I don’t know much about. Trey plays a similar instrument to the one that Tony uses, the touch-sensitive bass, but he attacks it more from a guitar angle. He uses guitar effects and he’s more apt to play something with a guitar mentality.”

Breaking it down, The Power To Believe evolves organically, each stride worthy of examination. “Level Five” is a hard-hitting instrumental that showcases the group’s extraordinary prowess as a highly functional ball of energy with a style that instantly interlocks and fires away. Belew tells me about one of the more evocative pieces on the album — “Eyes Wide Open,” a kinder and gentler Crimson number in the grand tradition of “Heartbeat” and “Matte Kudasei.” He cites it as another example of the symmetry that exists within the band.

“There’s a necessity for the softer side, the melodic side,” he says, pausing slightly. “‘Eyes Wide Open’ is funny to me. One day, Robert and I were sitting quietly in my studio trying to invent some more ideas and we started playing in the same way that we used to play in the ’81 band, that sort of interlocking guitar stuff that makes up songs like ‘Discipline’ or ‘Neal And Jack And Me.’ We hadn’t played that way together for a long time — 20 years, I guess. And we looked at each other and said, ‘You know what — we kind of invented this; it’s ours to use if we want to.’ And once that door was open, I felt like this is cool. It inspired me.”

Lyrically, Belew has always walked a fine line between being acerbically poetic and utterly absurd. He’s an avid reader, with a penchant to incorporate various influences and ideas into the mix. “Wordplay or global meaning or romanticism or spontaneous prose.” He reels them off. “It just depends on the material. If we’re writing a song and it comes out to be, you know, like neurotica, then I’m going to probably say, ‘You know this needs the hip jazz, fast-paced, spontaneous prose, go nuts kind of wordplay.'”

One new song in particular stands out for its truly unique brand of banter: “Happy With What You Have To Be Happy With.” As it turns out, the working lyrics, if you can call them that, were merely set up around the time signature of the song, never meant to stick. “We had this thing we were doing musically, where the band is playing in distant time signatures based around eleven. I thought this is going to end up on the cutting floor, unless I can formulate something to sing over it. Once I find something to sing over it, it legitimizes the idea somehow.

“So I worked for three or four days trying to come up with exactly the right phrase to sing against it. It ended up in a phrase eleven syllables long: happy with what you have to be happy with. Once I played that for the guys, it became a song. Suddenly, we’re strapping to see what ideas would go with it. We put together a lot of different arrangements and finally came up with one that everyone agreed on. Then they asked, ‘Now, what would you sing over this?’ And I said, ‘I haven’t had time to write the lyrics, but I know what I would do melodically.’ And they said, ‘Well, why don’t you send us a tape of what you think the melody would be, because we’re not sure of what to play until you develop the melody.’ So they went away and I quickly wrote down this sort of funny thing. (sings) ‘Well, if I had some words, I’d sing them here and I’d sing them like this and this would probably be the chorus.’ I did it in a joking manner for them to learn the melody. And everybody liked it so much that we kept it that way.”

I inquire as to how on earth Belew has developed into the songwriter and musician he has become today. He smiles at me in such a way that says I should know the answer. “I don’t know if I’d be able to write for King Crimson if I hadn’t had a year of schooling from Frank Zappa. Especially in odd time signatures. Before I joined Frank’s band, I didn’t know anything about odd time signatures. He sat me down and said to me, ‘I don’t usually play in 4/4, so you’re gonna have to play in 7/8.’ He taught me from day one. Without that real understanding, I don’t think I could have been a writer of ‘Three Of A Prefect Pair’ or something like that.

“So I owe Frank a direct debt in that way; but moreover, I think Frank was the person who showed me the ropes on how to be a touring professional, recording musician. The daily nuts and bolts that you need to know. And he imparted it to me in such a way that was hilarious, but it was also extremely educational and valuable. I don’t know how I would have fared if I hadn’t had his tutoring for that year. His music was so complicated that anything that followed it seemed easy. It really put me in the right frame of mind, to be ready to take on things like playing with David Bowie or being in King Crimson or making my own records.”

Speaking of which, when it comes to making his own records, Belew certainly hasn’t held back. Since 1982, he has issued over a dozen solo albums, along with oodles of collaborations and one-off projects. Recently, his first three solo albums originally released on Island Records have been polished off and re-issued on CD for the very first time. According to Belew, when Crimson inked a deal with a new company in Japan, they realized they owned the masters to Lone Rhino, Twang Bar King, and Desire Caught By The Tail and decided it was high time to re-release them in the preferred format. Belew couldn’t have been more pleased. “They did such a great job. The music sounds fantastic. The artwork is incredible. When I got those records in the mail, I just cried over them,” he laughs. “I was so happy they were available and done right. I must admit that they meant a lot of to me. They still stand the test of time. I think people will really be surprised. I was because I don’t have a record player anymore and I hadn’t heard them in years.”

With his back catalog in full bloom, Belew is gearing up for a new solo project he’s been working on in between breaks from Crimson and his other group, the Bears. “I have done a lot of my own material, which I work on, a little bit here and a little bit there. Now, it’s compiled itself to the point that I have more than 20 tracks and I’m real excited about all of them. I’m hoping I’ll get one big space where I can finish them off.” I scratch my head, finding this interesting in light of the fact that Crimson is in full swing and just about to mount a full-scale tour that’s taking them through the States and over to Japan.

Unabated, Belew continues: “What I’m going to do is put together a record that is sort of two different musical mentalities. One is the kind of current beat box, drum loop type thinking that people have in a lot of their records now. I feel I can take it to a different place. I’ve written ten pieces that are like that. They’re all in various states of completion. The second part of the record is a power trio, in the true sense of the word, bass, drums, guitar…maybe one or two guys singing … playing really muscular, aggressive music, not unlike King Crimson, but in a trio format.

“For this, I‘ve chosen to have Les Claypool and Danny Carey the drummer from Tool. So after I finish this weekend’s promo, I’m flying to San Francisco and we’re going to record there for 10 days with the three of us. It’s possible that Danny, Les and I will gather enough material to do a project apart from my solo record. So on this beat box kind of album with loops you’ll hear a door open up and suddenly you’re in a room with a live power trio.”

As if that isn’t enough on his plate, Belew confirms that an anthology he’s supposedly been working on for years is right on track and being prepared for release. “Dust is a huge compilation. It’s over a 100 tracks long and includes everything from my earliest work till now. It’s a 20-year retrospective, a box set.” Then he laughs before adding, “we’ll also put out a single CD called Particles…”

Amazingly, with so many extracurricular activities at hand, Belew says Crimson is still a top priority. “I’ve stayed in and been involved in King Crimson and in its various incarnations mainly because it challenges me. Every time King Crimson does something, you’re put on the spot to really do the best you can do. And do things maybe you didn’t know you could do. So it’s all about challenging and working at a high level of integrity. It has nothing to do with the normal machinations of a rock band. You’re not worrying about being on television or videos or anything like that. The whole idea of the game is to play something remarkable together. And that’s the tradition of the band. So, I’m really proud of being a part of that. I was a huge fan of King Crimson before I was in the band, and that’s how I thought of them — as being sort of a cut above your normal band. So now I look back 21, 22 years of being able to get in there and battle it out with one another. And it’s still great.”