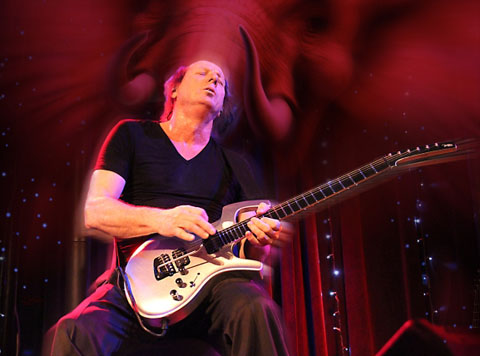

Adrian Belew is one of those mysterious figures in music you can’t pigeon hole. He first came on to the public radar as a sideman for Frank Zappa, which, as any musician will tell attest, is a definite high watermark on anyone’s resume. From there, it was on to gigs with David Bowie and Talking Heads before landing the role of lead singer and co-guitarist in King Crimson.

Even so, King Crimson was an intermittent commitment, which enabled Belew to play on other records (notably Paul Simon’s Graceland), form his own group (the Bears), and develop a solo career (20 albums so far). Today, he is known as a unique, one-of-a-kind guitarist as well as a songwriter and vocalist. Through it all, Belew has also been able to adapt and harness the power of new practices and technologies, while sustaining a sporadic pace on the road with the Crimson ProjeKCt and his own band.

Regrettably, I missed The Adrian Belew Power Trio with bassist Julie Slick and drummer Tobias Ralph when they came through Los Angeles in December 2014. However, I did get a chance to speak with Belew about current projects, like his music app FLUX, as well as touching on the time he spent with Frank Zappa, Talking Heads, David Bowie, Paul Simon and King Crimson.

~

FLUX is described as something that blends music and art into an interactive experience that never plays the same twice. I watched the video on the Kickstarter page, read through the materials, and I have a basic grasp of the concept. You say you believe the world needs a new way of hearing music. Can you elaborate a little on that? Why do you believe that?

Well, let’s look at the history here. For about 50 to 60 years now, you have basically the same format, especially for songs. You know, you write a song that’s got three verses, it’s got three choruses and maybe a bridge or a guitar solo; it runs three-and-a-half to five minutes, and there you go. That’s what you hear almost on every record you’ve bought for decades now. That has been the format. I find that a little stifling to have all the time. I find it a little out of touch with the way that I feel people process information now. As I say in the material you were reading, to me, the Internet has changed the way we think. It’s actually changed our brain process, whether we realize it or not. People get things in really quick bursts now, random things, short little bursts. I think there’s a place for music that reflects that as well. That’s what FLUX is supposed to be. I would say that doesn’t mean that everything else is moot. It just means that here’s something — an alternative. This is different. If you want to have music that suits more of an ADD kind of short attention span lifestyle that most of have, well, here’s an attempt at that. It’s songs; it’s music. There’s lots of stuff that you can hang your hat on. Things that are memorable, and things that are obtuse. There’s just a bit of everything in there. It goes by quickly and changes quickly. So if you don’t like something, just wait about 20 seconds — it’ll turn into the next thing. It is music that repeats itself over time, but every time you hear it, it may be a little different. The first time you hear a song, you may just hear the chorus. The second time you might hear the second verse and the chorus, or a guitar solo or a different guitar solo. So over time and repeated listenings, you kind of piece the whole thing together. Every now and then you may hear a song in its entirety. But the idea is to do something that’s kind of like life itself — always surprising, always being interrupted, always fresh. So every time you put on this new app — that’s what it is, it’s a music app you’ll download. Every time you put it on, you press play, you’ll get a half-an-hour’s worth of all kinds of material: sounds, sound effects, laughter, songs, pieces of music, guitar loops and who knows what. Every time you press that button for a half an hour, you get visuals with it, and they’re always different. You get kind of a little experience each time that’s different for you, and different for everyone every time. No two experiences are alike. It also contains, the app does, a lot of material — reading things about the songs or techniques we used in recording them, lyrics, back stories. You can “favorite” something — there’s a “favorite” button in the corner of the screen. So if you hear something you really want to hear again, press the “favorite” button. It automatically puts it in a playlist for you just like normal and you can go back and hear that piece or that song anytime you want. So you still have the advantages that you already have, but you also have this idea that you might be able to really enjoy something that just keeps coming at you differently all the time in pretty short bursts.

So, the technology of the app is able to manipulate the music in a way that makes it different every time — is that how it works?

No, the computer does not change the music at all. The reason it’s different every time is because we’ve loaded in — we’ve created, recorded and loaded in — hundreds of different versions of things and bits and pieces of things. So, for example, if I’ve written a new song, I might have six different versions of it. There also might be different mixes of it. There might be different sections that you just hear that section. There’s even some songs that I even change the words. In that way, the songs are different from time to time. In an overall sense, the whole experience is always different because it never comes the same way twice. So you might be listening to a song, and all of a sudden, someone’s car door slams and something else happens. That will probably never happen again in quite that same way. So with the visual, doing the same exact thing, changing with every single track, the effect is that it will always be different. When you put on a normal record, you know you’re going to get these 12 songs and they’re going to run in their particular order unless you press shuffle. This is far more advanced than that. Also, we have a lot of control over it. Built into the software, which took two years to design — a company in Amsterdam called Mobgen has been designing it for me — I have control over the probability of how random each single track is, for example, and I can change that. Another thing that makes it very different than other music form is I can actually change things in time, add things in time, upload new music, new pictures, whatever I want. So over time, it’s a continually growing piece of work, I would say. It keeps changing. To me, it’s like a new artistic platform to work from, in which so many of my ideas work that don’t always work in a regular record format.

You’re updating this constantly. You get up in the morning and record a couple of tracks and load it up?

At this point, I don’t have to do that right now, because we already have so much. But over time, yes. I wouldn’t use the word constantly because, of course, I’m going to be touring and doing many other things. But the idea is yes, over time, gradually, gradually. You’re right. If I wrote a new song this morning, I could record it today and have it in FLUX and you’d be hearing it tonight. That’s pretty different because it used to be I would have to wait until I had a full record worth of material, then record it all, then release it all — that longer process. This is far more immediate. In doing that, it also allows me a whole lot more freedom, what I can put in there because you need these little surprising interruptions — I call them snippets — that are three seconds, five seconds, 10 seconds long. What are those? They can be anything that I like the sound of. For example, I was in Europe a couple years ago and I went in my hotel room and I turned on the bathroom like. The fan in the hotel room made this incredible, strange, growling, strange, animal-like noise and I instantly recorded it for about 10 seconds. So, for example, you may be listening to one of my pop-ish type songs and all of a sudden — “bloop” — you’ll hear my fan there instead, my broken bathroom fan, for 10 seconds. It’ll change to something entirely different from there. There you go; you get the picture. That’s how it goes. You get it in about half-hour segments. So each time you press play, it’s going to play for about a half an hour, and that half an hour will be visually and musically different than any other half an hour.

And the visuals — are they just abstract images that kind of go along with the music, or is that going to change as well?

They are abstract images. They don’t necessarily go along with the music. Sometimes they’re triggered by the music and the music creates changes in them. There are various types of them that we created. Some of them are video-type loops that are actual films that are being manipulated, triangulated, or something like that. Other ones are things that must morph on their own; they change gradually over time. There are really various different types that we’re putting in there. I think it’s one of the things, in the future, we’ll even be able to put more stuff in over time so that realistically there will be as many visual changes going on to offer as there are musical ones. That way the changes of you never seeing and hearing the same thing twice are even greater.

Once you get this up and running, will you invite other musicians to participate as well, or give them their own FLUX channels? How do you see this developing?

We have a lot of thoughts on what could go beyond this. But the concept itself is unique enough but broad enough that it could be used for a lot of different things, not even just music. In terms of doing music, though, with other artists, yes; I would love to do that at some point in the future. Up to this point, I’ve done everything on FLUX. I’ve played all the instruments, done everything — singing, songs, all the stuff.

But really, I’ve done that because I wanted it to be my own personal statement to start from. Once that has been accepted — or rejected— then I will know how to proceed. But down the line, there are a couple different musical things that I want to do. One is to invite other artists into the party and get their little things that you can manipulate and throw in. Or, do that with their music for them. Or, a third thing is I wanted to do another line of FLUX, call it FLUX Classic; that would be material from me, from my catalog, my past, but it would be completely mixed together differently. So you would go back and say, one of my solo albums, and take parts from it and make new music from that and new snippets from that and new bits for FLUX, and that would make its own FLUX stream as well. There are a lot of thoughts for what could happen in the future, but it’s gotten almost five years to get to this point. If it’s something that people are really are excited by, I have 20 more things I’d love to do with it.

Will it be available in the Apple App Store and Google Play?

It’ll be available in iTunes — I think it will cost $10, $9.99, for hundreds of records, basically, and visuals. And then over time, there may come a time, a year or so from now, where I’ll offer a new package that’s another half an hour, hour’s worth of all new stuff. You can do that kind of thing with it too. But there will be along the way free updates and things like that to keep people tuning in. For someone who likes this, it’ll be a long time before they’ll have heard all of it and it’ll never be the same, so you’ll really never get to hear all of it in some ways.

This will be strictly for iPhones then? Are there plans for an Android counterpart?

For now, it’s for iPhone and iPad. Yes, the next step — and very important step for us —is to do it for Android, and that way we’ll basically have everybody covered. We want everyone in the world to experience it and enjoy it. But at this point, we have to start somewhere, and this is as far as we could take it at this point. To do android, now we’ll have to do everything we’ve already done before — recode all those hundreds of bits of information. That’s quite a chore for our programmers and software developers. At this point, we’re relying on, well, let’s see how well this does. We wouldn’t want to do it unless it’s something that people respond well to.

With your involvement with FLUX, does the idea of recording a regular album with regular songs every cross your mind? Are you working on anything in that area?

Yes, I do still have material that won’t fit in FLUX. So I want to make it clear, FLUX is not meant to be the only thing. It’s meant to be an addition to everything else. For example, the one thing that doesn’t work well in FLUX — the one ground rule that I established from the beginning — is that everything has to be relatively short. To keep that surprise element, to keep things moving along quickly, I try to keep everything really pretty short. Certain kinds of music, certain pieces of music, certain songs that need longer to develop — that need to be five minutes long or 12 minutes long — obviously they won’t work in this. Or let’s say, I’m not a dance artist, but let’s say I want to do a dance track; that’s something that needs to be the same groove for five minutes. You’re not going to put that in FLUX. Really, that wouldn’t work. So, yes. The short answer is yes, I do have plans to continue doing what I’ve always done and creating lots of different kinds of music. I also have plans down the line that I think we would do something with FLUX — say, maybe I would take my top 20 FLUX songs and make a record out of that and say, here are the complete songs; you don’t have to fish around and wait for them to happen randomly anymore. Here they are on CD. You can put them in your car and play them any time you want. That kind of thing is still going to be available as well.

Are you working on an album or do you have one planned for the near future?

I do have about a dozen pieces right now in various states. As I said, they really won’t work well for FLUX. They’re in formative states where some of them are near-finished and some of them are not. At some point, I’ll start committing those to record. But, up to this point, I have put every ounce, every second of the day into creating hundreds of things into FLUX. That’s what it requires more than anything — it really requires a lot of content. It’s made me very productive. It’s made me really have to scrape my creative brain just to get everything that I possibly like and get it in there for the first round at least. But I think, yeah, from this point on, I can continue to do FLUX and anything else I already do.

I spoke to drummer Terry Bozzio a while back and I asked him a couple of questions that I’d like to ask you. I think you know where this is going. First of all, tell me about auditioning for Frank Zappa. What do you remember about that?

At the time, I was a very green, young musician. I had never even been on a plane. So I took my first plane flight to California and ended up in Frank’s basement. They were preparing for their upcoming rehearsals. So people were shifting gear and moving things all around the room. Otherwise, there was just me and Frank. But it was really kind of chaotic, because there I was standing in the middle of the room with a microphone and a little tiny mini amp on the floor beside me. Frank was calling out things for me to try to play and sing, and I would do that. And then he would stop me and then we would go on to the next one. And then someone would move a piano in front of me meanwhile. It was very distracting. I felt like, wow. At the end of it, I realized I hadn’t done as well as I had hoped. I had nowhere to go. I waited around all day; I watched their very painful auditions. At the end of the day, when it was about time for me to get back into the van and have him drive me back to the airport, I finally had a moment with Frank and I said, “You know, Frank, I don’t think I did very well. But that’s because I thought it would be different than the way it was. I thought it would be just you and me quietly somewhere and I’d show you that I could do this.” And he said, “Well, OK. Let’s do that.” And we went upstairs into his living room, sat on his couch, and started the audition all over again — quietly, with no distraction. And about a third of the way through that, he stopped me, put his hand out, shook my hand and said, “You’ve got the job.” So it was a little hair-raising, but I made it.

In my mind, playing with somebody like Frank Zappa is akin to going to a prestigious music college like Juilliard or something like that. I would imagine you learn so much from him when you’re working with him. I was just wondering — is there one particular thing that he taught you? Something that you took home? Something that you live and breathe to this very day? Something that he gave you?

I often say about my year with Frank, I was like a little puppy dog hugging his sleeve all the time. I was absorbing every little thing that he could say or teach me. I lived with him on the weekends for three months. That’s the way I was able to learn material before the band got their music. Because I’m self-taught, I don’t know how to read music. So that put me into my own little category of rarity in the world of Zappa. He took on someone who he would have to kind of teach man-to-man. So I had a lot of time with Frank. And I often say, more than anything, he taught me all the nuts and bolts about being a professional touring artist and recording artist and having your own business and having all the nuts and bolts about being in the music business. I mean, the musical part of it was only one part of it. The thing that I think I took home from most of it is just how to do this — how to be a recording artist and how to make records, how to master a record, how to tour, how to do everything. He taught me all of it in one year. Musically speaking, I would say there was really one major thing that he showed me from the very first night that I went home with. He said to me, “I don’t usually play in 4/4, so you’re going to have to learn how to play in odd time signatures.” He started right off; he showed me a little guitar exercise I could take and start working with to play in 7/8. I realized very quickly from his tutelage that it had nothing to do with counting or anything like people might say, “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven.” It’s not that. It has to do with accenting. There are certain accents that make up a seven; there are certain one that make up an 11 or a nine or a five or a 13, and there’s various ways you can do them in most cases. So once I caught onto that, then I was able to walk into some of the more complicated things he was doing. And because I have a rhythmic background and started as a drummer and still play drums, it wasn’t as difficult for me as it might be for some other unschooled musicians. But I’ve always thought that that was super important to me musically. From that point on, I began writing using those techniques. And probably the 32 years I spent in King Crimson writing music in one time signature and singing it in another would have never been able to happen had Frank not shown me that.

I guess that’s radically different from working with someone like David Bowie or the Talking Heads, then.

Absolutely. You know, David Bowie and the Talking Heads are very similar to me in my memory of everything. They both just wanted me to go wild on guitar; that’s what they needed. Nice to have some back-up singing if you want, but that was not as important. They both had singers. What was really important to both of those bands is that you brought someone in who could really sort of throw a lot of wild stuff in there when needed, and otherwise just color the arrangements a bit. I fit that role really well and enjoyed that role a lot. So I was given a lot of freedom in their bands. But the music, if you think of it, is pretty straightforward. Especially the Talking Heads — a lot of their music is just in one key; it’s in 4/4, just kind of groove music. So what did they need over top of that? They need some wild guitar solo playing. So OK, there you go. Those were fun bands for me, but they didn’t challenge me in the true sense that King Crimson or Frank Zappa does.

What about playing on Paul Simon’s Graceland? What was your job on that one?

Paul Simon was one of the very few guys that I’ve worked with who really wants you to play something exactly the way he wants it, and he will sit very patiently — almost tediously — saying, “Yeah, I want you to play this E chord; now, put a little more tremolo on it. OK, now let’s try it without the tremolo. Let’s try it with you strumming it. Let’s try it with you picking it.” He’s one of those guys. So you don’t have really — I didn’t, at least — you don’t have much creative freedom with Paul. That wasn’t what it was about. He was looking for me to bring unique sounds to his music. And the parts themselves —you know, something like, “Daa da-da-da; daa da-da-da-da” — that’s me playing that and that was him, saying, “Here’s the notes. Here’s exactly how I want you to play it.“ That almost never happens to me. When I play with Nine Inch Nails or pretty much anyone I go in the studio with over my career, they just want me to do whatever wild thing I could think of. Paul came from a different viewpoint — I really enjoyed that too.

When you worked on that record, your first stint with King Crimson was already over, if I’m looking at my history right.

That’s right.

You were with King Crimson, and then you went on to rejoin King Crimson in the ’90s, and then again in the early 2000s right on through 2008. Of course, you’ve played with other factions of King Crimson since, most recently the Crimson ProjeKCt with Tony Levin, Pat Mastelotto, Markus Reuter, Tobias Ralph and Julie Slick.

Yeah, we did several couple of years with them. In fact, this year, with Crimson ProjeKCt, we went to Europe twice for five weeks each time; with the Power Trio, we went to Australia as well this year. The Crimson ProjeKCt really became my outlet for being able to continue to play the songs I love from my time in King Crimson and celebrate that music with some of the authentic players from that band. It’s always been a joy to do, but at this point now, they’ve started a new Crimson without me, and they play more of the material that existed from before I was ever in the band. So it obviously wasn’t right for me to be in the band. So I don’t know where Crimson ProjeKCt will go from here, whether they will continue on. Depends on how much more the new King Crimson does or doesn’t do.

I saw that version of King Crimson and you’re absolutely right. They’re doing mostly the stuff from the mid 70s, the stuff with John Wetton and earlier stuff. I guess you found out about not being part of this through Facebook.

No, Robert [Fripp] emailed me.

Were you surprised by that?

Yeah, I was pretty surprised by it. He had already told me for the last three or four years running, every time I’d ever talked to him, he would say, “No, I don’t want to tour ever again. I’m not going to do anything. I’ll never play live again. I’m done, and blah, blah, blah.” I kind of always suspected that was not written in stone, so to speak, because Robert is that kind of guy — he’ll change his mind. But it did kind of catch me off guard that he would want to do the band without me. Once I learned what they were doing, it made perfect sense to me. And to be honest, it wouldn’t have been a good time for me to start up a new lineup and start trying to create new Crimson music because I’m really so enveloped and absorbed in what I’m doing now, solo stuff. So it worked out for both of us.

Do you foresee a time where you might possibly work with Fripp again in any capacity? Because I know you guys did the different parts of King Crimson throughout the years. I mean, you guys worked together forever. I mean, I was kind of surprised.

Yeah, I’m still a little surprised by it, but at the same time, I feel like, well, I don’t know the future and I don’t really want to make any kind of premonitions about it. There’s a part of me that figures that maybe Robert will stop after this; maybe he won’t. Maybe he’ll want to do something new. Maybe he’ll want to continue this. I don’t know. So I can’t really think too much about it. I’ve got to go ahead and have my life. As to the question about whether or not I would want to do it again, it would depend on the time, the circumstances, who was going to be in the band, what else was going on in my life — so many other things. I feel at this point — having done three decades worth of work on something — I feel like, well, I’m happy with what I was able to do, what I was able to help with that. I’m happy with the results. If it happens further, that’d be great. If it doesn’t, that’s great, too.