By Shawn Perry

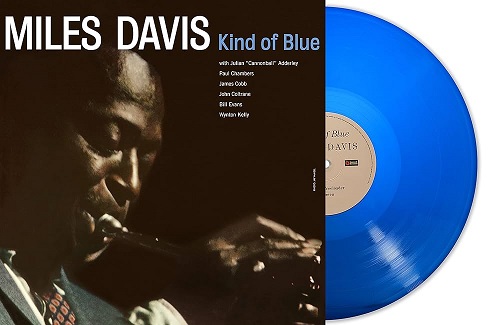

Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue was recorded in the spring of 1959, over two sessions — one on March 2 and the other on April 22. I was born on a day that fell between these two dates, so I feel like I have some strange, cosmic connection with the album. Maybe they were waiting for me to make my arrival before they decided to finish it. As much as I would like to believe that, there’s no doubt Kind Of Blue raised the bar up high, causing a seismic shift in the jazz world, and becoming the quintessential album for the ages.

Fifty years later, it still tickles the ear drums, breezing through one emotive, modal stroke of the brush after another. Kind Of Blue is very much like what Bill Evans described in the liner notes that appeared on the original record’s back cover: “Something close to pure spontaneity.” The impact the record has had on improvisational playing in both jazz and rock cannot be underestimated. Bands such as the Grateful Dead and Steely Dan have embraced modal elements to enlighten the breaks and extend the journey.

Though its roots run deep, the five pieces of Kind Of Blue are molded from simple, practical building blocks. Woven together, the components create something else altogether — something indescribable, smothered in a payload of Zen-like conciliation.

My discovery of Kind Of Blue didn’t occur until I’d already sampled Miles Davis’ records from the late 60s and early 70s. I got into In A Silent Way, Bitches Brew and A Tribute To Jack Johnson, just as I was learning about Return To Forever, Weather Report and Mahavishnu Orchestra. Like any artist you stumble upon midstream, I went back and discovered the man’s rich history, a life that parallels more than a few major developments and innovations in jazz and music, in general.

What I found out early on was that listening to Kind Of Blue is almost like a religious experience. I remember being in Las Vegas a few years ago with a couple of buddies who had just flown in. We were sitting in our suite, I was raring to hit the town, and these guys wanted to kick back after their flight.

I told them I was going to hit the tables, and I’d meet up with them later. Before making my exit, I put on my Kind Of Blue CD, lowered the lights and sneaked out. Later that night, my friends told me the CD changed their disposition; they felt rejuvenated, at ease, ready to go and soak up the Vegas vibe. To this day, whenever I see them, they inevitably bring that night up.

Which isn’t to say Kind Of Blue is what you could call an “up” record. It is, in fact, kind of blue, perhaps melancholy in spots. At first, you’re thinking those first few tinkles of the ivories in “So What” are setting the scene for what’s to come. Then you find out you couldn’t be more wrong the second Paul Chambers picks out that simple, alluring bass pattern. Then Jimmy Cobb plays a fill and crashes the tempo for a free-form folly built around a power of trio of blazing horns — Miles Davis on trumpet, Cannonball Adderley on alto saxophone, and John Coltrane on tenor saxophone.

Once I began to appreciate the atmospheric qualities of the music, I picked up on the effortless style and certain momentous instrumental passages. Wynton Kelly countered Bill Evans by introducing a livelier, jauntier edge on “Freddie Freeloader,” based on a harmless real-life bartender named Freddie Tolbert who gained a reputation for “freeloading” his way into jazz’s inner circle.

For most of the record, however, Evans’ influence is ubiquitous. He sustains the brevity, beauty and tenderness of “Blue In Green” before driving the vampish “waltz-like bounce” of “All Blues.” Inspired by the pianist’s 1958 composition for solo piano (“Peace Piece”), “Flamenco Sketches” is a classic example of modal jazz, bejeweled by a series of staggering solos that defy easy compartmentalization. He may not have received the proper credit, but Bill Evans is arguably the heart and soul of Kind Of Blue.

Released on August 17, 1959, Kind Of Blue was the new definition of “cool, calm and collected.” Columbia Records had no problem promoting it to the top of the jazz heap. The critics loved it, radio played it, and the Miles Davis sextet rolled it out live for a few choice performances before imploding and scattering into different directions — Adderley returned to his solo and session work, Evans started his own trio, and Coltrane recorded Giant Steps in 1959 (it was released in 1960), eventually chosing to take a more spiritual path with his music. Kelly, Chambers and Cobb made a few records together and appeared on subsequent Mile Davis records. The players may be long gone, but Kind Of Blue is still the best-selling jazz album of all time.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the album’s release, several promotions and celebrations are underway. Sony has repackaged Kind Of Blue in a number of attractive configurations. In the fall of 2008, The Kind Of Blue – 50th Anniversary Collector’s Edition box set, filled with essays, photos and variations of the record, sounded the alarm to remind everyone of the album’s upcoming golden anniversary.

The Genius Of Miles – The Columbia Years photo exhibit in Beverly Hills featuring shots of various periods of the musician’s life, along with various Kind Of Blue swag, and even a few close associates and family members of the man, was enough to encourage this writer to race home and throw on the SACD for its usual comforting factor.

Somehow, the double-CD Legacy Edition — a remastered version of the album, along with outtakes, alternates, live and condensed liner notes (the first CD includes a PDF with an enhanced digital booklet developed from the box set) — has replaced my SACD in its usual rotation. The first CD has the album and a few negligible takes. The second CD is the pearl in the oyster, featuring four numbers from May 1958 — “On Green Dolphin Street,” “Fran-Dance,” Stella By Starlight,” and “Love For Sale.” These were the first recordings by the sextet. There’s also a frantic, 17-minute live version of “So What” from a show in Holland on April 9, 1960.

As if expanded versions and essays weren’t enough, there’s a Kind Of Blue documentary on DVD that tells the whole story. Praise from the likes of Bill Cosby, Ed Bradley, Herbie Hancock and many others substantiate the record’s importance as a cultural phenomenon as well as a musical one. “It is one of the single greatest achievements in recorded music,” Bradley proclaims. Hancock adds: “It’s cornerstone record not only for jazz; it’s a cornerstone record for music.” Between the accolades, there are intriguing insights into the making of the record, as well as pristine performance footage capturing the interplay and genius of Miles Davis. The DVD comes in the box set, and is be released as a standalone in early June 2009.

Jimmy Cobb, the sole surviving member from the Kind Of Blue sessions, is making the most of the record’s anniversary by participating in many key events. He appeared on a special Q&A panel at the 2009 SXSW festival, alongside Ashley Kahn, author of the book Kind Of Blue: The Making Of The Miles Davis Masterpiece (Da Capo Press). Cobb and his So What band are also on scheduled to play selections from the album at the Playboy Jazz Festival and other festivals around the world.

Any music fan will tell you there’s an ounce of the supernatural — a magical potion?— that works its way into the grooves of certain classic albums. Whatever was in the air during those two sessions in 1959 may be something only the great mystics and alchemists can conjure. The actual process, after all, fell together rather easily. Davis and Evans literally sketched out a few ideas and presented them in the studio just prior to recording. From there, the progression of events assumed an organic skin.

Like construction workers erecting a grand monument for all to observe and marvel at, Evans and Chambers anchored the basic framework. Cobb painted the drums blue with his delicate brush work and transitional cymbal accents. Davis, Coltrane and Adderley blew in the flourishes — pushing, pulling and stretching the canvas of chord sequences, dressing the melodies and interludes, giving flight and fruition to each and every turn.

Tossed all together, a miraculous scent erupted — undemanding yet impossible to ignore. Without it, who can say what kind of music we’d be listening to — kind of foggy, kind of boring — who really knows? The chemistry of the players, the time of day, the smell of the studio and the alignment of the stars — these are what fell into place, creating the aura and the mastery that encompasses Kind Of Blue.