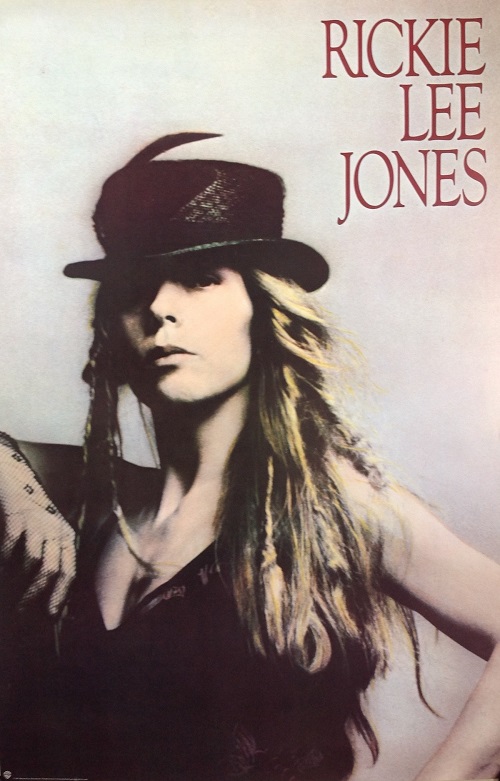

Select photos courtesy of Michael Halsband

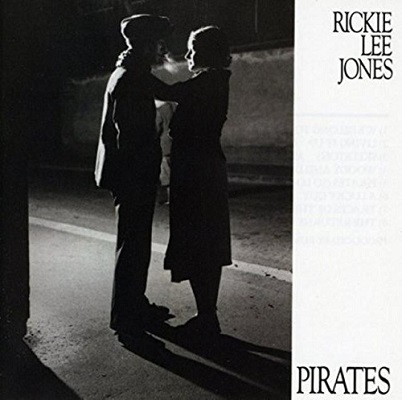

When Rickie Lee Jones set about making the follow-up to her smashing success of a debut album, she could have easily coasted with an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” creative mindset.

Instead, she chose to break down her musical formula and start from scratch.

While Rickie Lee Jones would go platinum (on the strength of the Number 4 hit “Chuck E.’s In Love”), boast the best of Warner Brothers’ musical lineup (i.e., Randy Newman, Michael McDonald, Dr. John), and garner her a pair of Grammy awards, Pirates — turning 40 years old this year — would feature a more mature Rickie Lee, one who transforms heartbreak, classicism, Leonard Bernstein, and introspection into an artistic opus. It’s an album that would have Rickie Lee tossing her ubiquitous beret off her head in a quest to be taken more seriously as an artist.

“We knew we had a special record in the cans. As it took shape … we could sense this incredible new music. We thought we’d have a bit of success, but it was much bigger, of course, than anyone might have imagined, and to be sure, much more success than history seems to have recorded,” Rickie Lee told me via email about her debut album, adding that when it came to Pirates, “The songs were all new. There were no demos except my playing them on piano.”

Where Jones would arguably come off as the supposed progeny of Leon Redbone on her debut album, she drove her hands and talents into a piano for album two. The results would yield such lush lyrics as:

“How could a Natalie Wood not get sucked into a scene so custom tucked?”

“Shall we weigh along these streets young lions on the lam?”

“There are always magnets pulling each of you there, living every story, you’d dare to be the only ones…”

“Pirates was different because all my life I had wanted to play piano, but my family couldn’t afford one. After the first record I rented a piano and played every day. The songs were made meticulously, me playing the melodies I heard in my head and then practicing them over and over,” she said. “I heard music in my mind; I translated emotion into music. Or perhaps I simply feel emotions as music. The job is to translate them into this world.”

What makes Pirates unique is that it isn’t a concept album per se, yet it boasts a unique cast of characters and jazz-like movements that change as much in emotion as they do time signatures. Rickie Lee builds her songs up slowly, using the piano’s 88 keys as a canvas to paint the kind of narratives that could have spurred William Kennedy to go off and write his revered Albany trilogy.

“Steely Dan had a big impact on this music. Little gems like “Skeletons” are inspired by great writers like Randy Newman,” Jones told me. “I was spending time in New Orleans and Los Angeles. I liked the brass ‘ain’t nothin’ but a party’ chaos of The Big Easy and my own life, so that was probably how “Woody and Dutch” came about – a simple R&B guitar line I made up a song over. I had been carrying “West Side Story” with me all my life.”

“Traces Of The Western Slopes” bears the strongest Steely Dan influence as the eight-minute track can be considered Jones’ own Aja. The mood and tempo of the piece slows, then intensifies, then slows again into virtual cigarette smoke. Perhaps it’s not coincidental, Donald Fagen would play synthesizer on the album. Late Steely Dan member Walter Becker would go on to produce her 1989 album Flying Cowboys.

Another influence sparking the album’s music (though Rickie Lee likely inspired him just as much, if not more, than he did her) is Tom Waits. Romantically linked at the end of the 1970s as the gravelly-voiced disciple of Howlin’ Wolf and Captain Beefheart churned out stellar albums reflecting the “wasted and wounded” (Small Change, Foreign Affairs, and Blue Valentine), their breakup permeates throughout Pirates, including on such wistful tracks as “So Long Lonely Avenue” and “A Lucky Guy.” Yet one should make the case that Jones turns any apparent heartbreak into magic. Where Waits would immerse himself into a darker, moodier sound for his forthcoming Island Records discography, Rickie Lee would channel Dylan and Joni Mitchell, punctuating her artistry and breathy vocals with classic jazz all the way.

“I was not prolific, and critics had really mixed feelings about me. I did not fit in, just could not pick up that rock star scepter and rule,” Jones told me. “I think the record has not received the lasting praise it [should] due to two reasons. One, I am a woman. Two, I kept singing jazz and that really made people confused. But I was just trying to expand the allowable genres a singer songwriter could cover. And I think I did that.”

Should you listen to any track on this album, it should be “Living It Up.” Built around a soft chord structure and imagery reflecting Bernstein’s Sharks and Jets as well as a bevy of characters that would make Springsteen proud, Jones ramps up in musical rapture and the possibility of anything. This culminates in near-euphoric chanting of the album’s title. It’s not a song designed for three-minute single success. It’s a new “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)” to formally kick off the new decade.

Per Jones: “That song took the longest. It started in Olympia when I wrote [it] at the Catholic college there, sitting in the music room. I played the chords of Pirates. Maybe the first inklings of ‘Living It Up.’ When I got to New York City nine months later, I rented a place with a piano. There, at night, I played the chords, moving the right hand and keeping the left hand still. It was odd inversions because as I said I did not know piano so had to find my way. Braille. And the thrilling part — the bridge before the bridge — ‘Well at first when it was this way’ — those whole step chords against each other that became my signature, I suspect they come from West Side Story and Stravinsky, maybe. The joy of the middle — ‘Oh yeah, we’re living it up!’ — just bubbles out of the heart. It’s so young, isn’t it?”

She adds: “The lyric I think evokes this hopeful thing because I made a happy ever after for my imaginary people, even though their real counterparts would never speak again.”

While Pirates would reach the Top Five of the Billboard album charts, it would roughly sell half of what her debut sold. However, the album found a critical champion in Rolling Stone, which upon its release gave the album five out of five stars.

“The rare five-star review in Rolling Stone set me up as a kind of high point in women’s music, I think. In fact the record was weighed less as a woman’s record and more as a rock record, and this one thing I think made it unique,” Rickie Lee said. “I went past what was ‘expected’ of women at the time.”

Unfortunately, not everyone agreed.

“I actually read a very sexist and cruel review saying that my record was one of the mistakes of Rolling Stone,” she adds. “It is weird to live so long, to watch your work become part of the great work that follows, and then people turn around and say yours was never really great at all.”

From Pirates, Jones would go on to release a unique and entirely original repertoire, including the underrated The Magazine of 1984. Still releasing new work to this day, I asked what else the soon-to-be 40th anniversary of Pirates sparks in Rickie Lee. Her response:

“One thing for certain. Playing the music live is very different than listening to the recording. It’s hard work, and unlike any other record of mine, it demands we play it as written.”

Which leads to perhaps the greatest quote of all:

“That only indicates to me that it should never have any imitators.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s new book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.