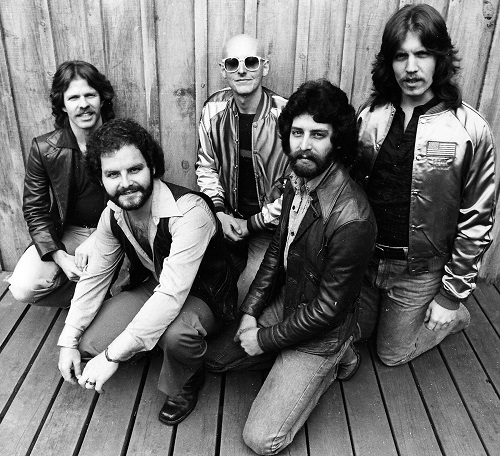

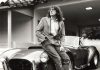

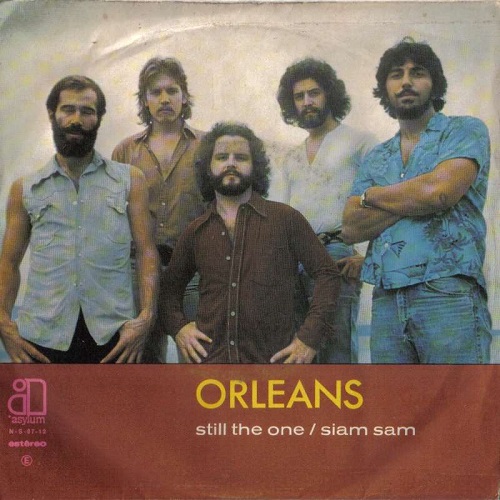

Photos Courtesy of Lance Hoppen

In 1976, the group Orleans came within reach of superstardom.

With two tender Top Five singles under its belt — “Dance with Me” and “Still the One” — and its reputation solidified as opening act for Jackson Browne’s Running On Empty tour, the group should have been on cloud nine, both commercially and artistically.

Instead their cloud of success turned stormy. Band tensions led to member John Hall departing the group for the first time.

“I think our manager, our producer, and the record company should have all sat us down and maybe got us a therapist. If we did group therapy it might have gone differently,” Hall told me recently. “I’ll speak for myself, I don’t think I made the best decisions, but it’s what happened.”

For Orleans bassist Lance Hoppen, Hall’s departure came “completely out of the blue.”

“That created chaos and a ‘what are we going to do now?’ scenario,” he said.

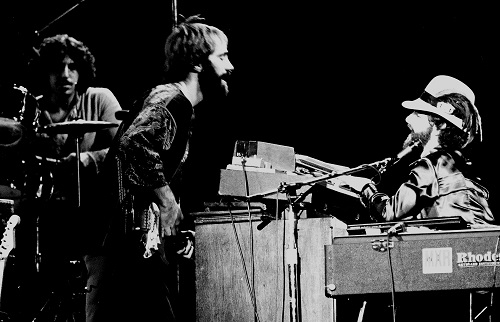

Four years in and the group was at a major crossroads. Forming in 1972 with the nucleus of Hall on vocals and guitar, Hoppen on bass, his older brother Larry on keyboards, guitar and vocals, and drummer Wells Kelly, Orleans would dutifully cut its musical chops across the country, prompting Rolling Stone to dub them the best unsigned band in America.

Then came the meteoric hits.

“Throughout the history there was a lot of talent in a limited amount of space,” Hoppen said. “John was the driving force, for sure. He’s a Leo – he’s a lion and he had the most credential and experience. He and [his wife] Johanna wrote prodigiously and very well … Larry also wrote a lot and sang a lot and Wells wrote and was constantly trying to get his musical voice in the mix. He did but in small measure. So, there was a lot of internal combustion and that was what led to John leaving, I think.”

While Hall would go on to a successful solo career and spearhead the anti-nuclear energy Musicians United for Safe Energy (MUSE) activist movement and concert series, Orleans opted to press on. This marks a unique period of creativity for the band — one that deserves to be rediscovered. Adding new members Bob Leinbach and R.A. Martin and composing new demos, the group also went in search of a new record label. It came down to a bidding war between Epic Records and MCA subsidiary Infinity. The latter would win given its fervor for a new Larry Hoppen composition — “Love Takes Time.”

“Love Takes Time” may fall under the radar of music fans but is actually the band’s third biggest hit, peaking at Number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1979. With Hoppen front and center, his vocals take on new energy and range as the sentimental song, in some ways, outshines the group’s prior hits.

“I think it had hit written on it, but we never could predict those things,” Lance Hoppen said. “We didn’t predict ‘Dance With Me;’ we didn’t predict ‘Still The One;’ we didn’t predict ‘Love Takes Time.’ We go about doing what we do and see what happens. But the label heard it as a hit for sure and that was why they signed us.”

Hoppen adds: “It always irked Larry big time that people thought John Hall was the singer. He was living in the shadow that wasn’t real and John got credit where it wasn’t due. Larry was of course determined to prove a point and that’s what ‘Love Takes Time’ was about. And he did prove a point. As co-writer of that and singer, he certainly left a mark.”

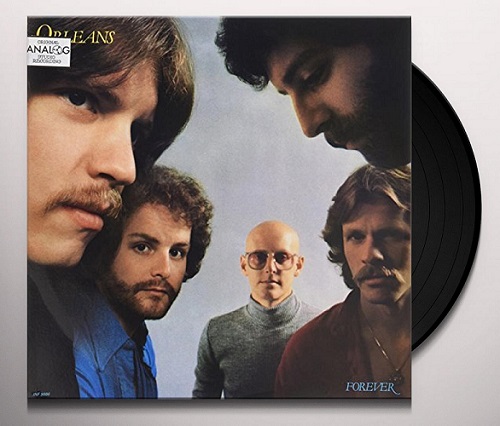

Orleans’ first album without Hall — 1979’s Forever — is a valiant effort driven largely by the power of “Love Takes Time.” Yet it showcases how gospel is a genre the band isn’t afraid of tackling. Such examples include Leinbach-led tunes like “Slippin’ Away,” “Keep on Rollin’” and “Everybody Needs Some Music.”

Still, the album had wear and tear on it from the get-go, according to Hoppen.

“We just worked endless hours, overspent our budgets big time and pretended we knew more than we knew as producers, but we didn’t,” he said. “Luckily, we got a hit out of it, but it was at great expense.”

Yet, to this day, even Hall tips his musical hat to the power of “Love Takes Time,” especially with being back in the band.

“I was happy for them. I was happy for Lance and Larry and the other guys, all of whom I’ve worked with at one time or another,” he said. “That song also continues to be a chestnut that we do today.”

Even with its second wind still blowing, Orleans would be back at square one come 1980.

“That quintet had its pros and cons. It was only a one guitar situation and two keyboards, which was kind of weird from where we had been. But it had its own merits too,” Hoppen told me. “We did a good job. It just was different, and it was relatively short-lived in that Infinity went out of business. That was the end of that.”

While the band aspired to get out of its MCA contract, they found themselves at the label’s mercy for another album. The result was the group’s second eponymous record, released in 1980. What stands out here is the fact everyone who had ever been in Orleans up to this point played on the album even though the album cover depicts only three members – the Hoppen brothers and Kelly.

“No Ordinary Lady” from this album sounds like it comes right out of Chicago’s late-70s, post-Terry Kath playbook. “Come On Over” and “Ann Marie” are other strong tracks, reflecting more of a straightforward rock mindset for the group.

Orleans would release one more album in 1982 (One Of A Kind), featuring guitarist Dennis “Fly” Amero (a member of the modern Orleans quintet), but after dwindling sales and management squabbles, the group was put to bed in September 1984. It’s important to note that One Of A Kind isn’t a bad album; it simply tries too hard to replicate the synth-driven sounds of its time. Tracks like “Beating Around the Bush” are a bit difficult to take seriously as well, given this is the same group who, only a few years earlier, penned such gems as “Half Moon” and “Let There Be Music.”

Orleans would reform under unfortunate circumstances — the untimely 1984 death of Kelly. Joining together at a memorial in upstate New York, the Hoppen brothers and Hall would sing and harmonize together for the first time in years.

“It was magical — I could hear that. We all could hear that,” Hall told me. “We all decided to get back together and work together again and I’m glad we did.”

A move to Nashville and a fresh start resulted in the trio of the Hoppens and Hall releasing one of the strongest efforts in the Orleans discography, 1986’s Grown Up Children. While there are country tinges all over the record, it’s not specifically a country record, despite its polished production touches courtesy of Tony Brown and David Hungate. Standout tracks that emphasize the group’s newfound energy and direction include “Speed of Love,” “Fly Away” and “Circles,” a poignant ballad first released on One Of A Kind.

“We weren’t really a country band. I think radio people knew that and the audience knew that. That was a record that had a particular sound and style,” Hall said. “I think it’s a good record, but it never achieved the success MCA Records thought it would or could and we hoped it would.”

It would be another eight years before Orleans would release an album — 1994’s Analog Men. Another studio effort, Ride, would come out in the new millennium.

Sadly, the band’s toughest obstacles were still yet to come.

“There’s a lot of short stories from 1980 to 2019,” Hoppen told me. “The gist of it is that for 47 years — with the exception of five or six maybe — we’ve been playing as a touring band every year with at least two of the original guys, if not three, at all times even though those two may have shifted. It’s a really deep, long winding trail with a lot of details and aspects.”

Larry Hoppen would take his own life in 2012. Per younger brother Lance: “It was really tragic and beyond curious.”

Larry Hoppen is not a major vocal presence on Orleans’ first two albums – its eponymous 1972 debut and 1974 follow-up Orleans II. It would take the group’s third album, Let There Be Music, and the airplay power of “Dance With Me” – penned by Hall and wife Johanna — for Hoppen’s vocals to hit the collective ears of America.

“His innate voice was quite unique and strong. People remember that about him,” Lance Hoppen said. “But he’s not a well-known name … He never got the notoriety, but he’s well-loved in retrospect by many, many, many people.”

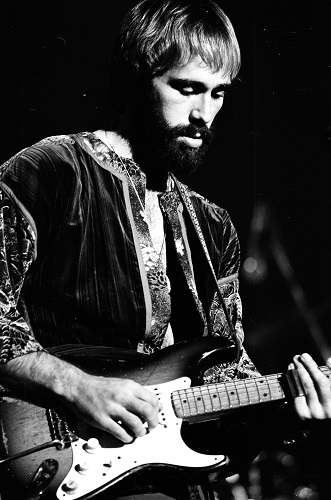

Hall told me Hoppen’s talents stood out from their very first meeting – a jam session in the Soho loft of bass player Harvey Brooks (best known for backing Bob Dylan during the Highway 61 Revisited era).

“At one point I started playing the melody to the “Age of Aquarius,” the song from Hair, and from across the room I heard this other guitar playing a third harmony above my guitar. That was Larry. He immediately heard it and immediately started playing harmony. Of course, the double lead guitar harmonies became a real trademark of Orleans and after that jam I walked across the room and shook his hand and said, ‘I’m John Hall.’ He said, ‘I’m Larry Hoppen.’ That’s how we met. He just was an extraordinary musician.”

When asked what else people might not know about Larry Hoppen important to include here, Hall added he “had a soft spot in his heart for people who needed help.”

Despite the tragedy of Hoppen’s death, younger brother Lance was determined to have the group persevere. Hall would officially rejoin the band for the second time, following his tenure as a New York Congressman in the House of Representatives. Another Hoppen brother — Lane — would join the quintet.

“I said the question isn’t if we’re doing it, it’s how are we going to do this?,” Lance Hoppen told me. “I did not want to go out with a whimper and disappear.”

Looking back on the factors that led to the first true incarnation of the band breaking apart, Hoppen and Hall offered the following:

Hoppen: “It was a five-year uphill climb starting in ’72, foothold in ’73, first hit in ’75, second major hit in ’76 and then blow it up at the end of ’77. It was a good trajectory, we just didn’t have the wherewithal, the knowledge, the maturity to harness the power inside and not let it blow up like an atom bomb, which it did. In retrospect everybody learned that it was a really bad idea because even though John had success and we had success, Orleans never had the kind of success we might have had had we just not thrown away that moment because momentum is hard to regain.”

Inspired by the popular music coming out of New Orleans at the time — Allen Toussaint, Neville Brothers, and The Meters included — the group would play a rigorous circuit of regional gigs, spreading word about itself organically.

Hall: “We had a really good show, I think it was in Oswego, New York, and the promoter wanted us back, but we had to use the same name or people wouldn’t know to come. For weeks we felt if we were going to change the name we’d have to do it fast and we never did. The name of the band took on whatever meaning we gave it through our music.”

Hoppen: “That original quartet — that was really magical. That was something special that has never been recreated. Once you take a piece out of that equation, it’s never the same. That quartet in its raw form was a real crowd igniter.”

Hall: “We made some really good records and some really good music. The band Orleans has a vocal blend that’s not quite like anybody else but is really good and people seem to love. We’ve always prided ourselves on our instrumental work and the rhythm tracks that we’ve done and recorded and played live and we’re pretty good soloists on top of that.”

For anyone who thinks “Dance with Me” and “Still the One” were easy to craft in-studio, they’d be sorely mistaken. The group’s two biggest hits took a hat trick’s worth of tries to reach their finalized forms. “Dance with Me” even appears on the group’s second album, albeit a tad slower and in a slightly lower key.

Sudden hitmaker status may have prompted listeners to think of Orleans as solely a pop band — a true misnomer, according to Hall.

“When we did ‘Still The One’ and ‘Dance With Me’ and when the band did ‘Love Takes Time’ when I was not in the band, those songs put us in a pop category that gave some people in the rest of the country a different impression than what we were actually doing,” he said.

Yet other classic Orleans tracks like “Reach” and “What I Need” emphasize how the group was always driven by groove. Hall adds there is even a noticeable groove to “Still The One.”

“I remember years later James Taylor told me that the first time he heard it he had to pull over to the side of the road because the groove was so locked in that he kept wanting to speed us his driving,” he told me. “There’s a strong rhythm to that tune. It’s not the kind of funky R&B influenced rhythm that ‘What I Need’ or ‘Waking And Dreaming’ or some of the other songs have but it definitely has a kind of groove and that’s something we always kind of prided ourselves on.”

The version of “Still The One” we hear to this very day on radio and iTunes was almost shelved for good, according to Hall. Two minutes and 39 seconds into the song, Hoppen’s voice suddenly appears to shift vocal ranges flawlessly. It’s not a vocal trick; it’s due to a flaw in the tape.

“The oxide in the middle of the two-inch tape right where his track was came apart and a flake of it was on the floor. We were going ‘Oh, we ruined it. We’re going to have to redo the whole thing,’” he said. [Producer] Val [Garay] said, ‘You guys are crazy. This is a great record and let’s just mix this. That’s the version that’s out. It’s really important, I think, to have other ears besides those people who were closest to it and we were fortunate to have those people.”

I tried to avoid asking Hall and Hoppen about both hits, knowing they’ve been asked about them an umpteenth number of times. It proved to be wishful thinking. I mean, without those songs, we wouldn’t have Orleans in all its varied, unique and individual incarnations.

“Looking back at my age now, there’s no way I can say having a hit was a negative,” Hall said. “I mean maybe there were certain things in terms of what kind of music we were expected to do after that that might have put us in a little cubbyhole, but it was always our music. The fact that we’re still working today means that the songs are really spreading the word and that people still love them and want to pay to hear us sing and play them and download or stream the songs. I hear them in the vegetable aisle in the supermarket.”

Per Hoppen: “Those three hits are why we’re still able to work 47 years in, but nobody predicted any of that. It’s not lost on me that it says, ‘We’re still having fun.’ When it was fun it was really fun, and we couldn’t get enough of it. When it wasn’t fun, we couldn’t do it. We put it away. Once it became fun again, we would do it again and then when it wasn’t fun we put it away. That was the up and down of it. These days when we open a show, we have the announcer say, ‘Forty-seven years and still having fun — Orleans’ and that’s how we like it.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.