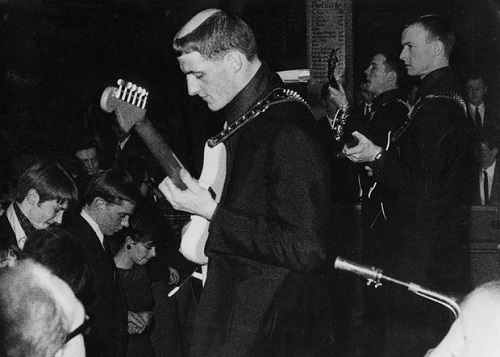

Photos courtesy of Eddie Shaw

It goes without saying that 1966 proved to be one of the most pivotal years in the history of popular music.

Sure, we would get Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys and Revolver by the Beatles, but this would also be the penultimate time when rapid fire garage rock blasted onto the airwaves — defying conventional formats and aesthetics by cutting to the musical chase and turning the volume up…way up.

Out of this genre would come pure classics, many released that same year — Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention’s seminal double album debut Freak Out! (who doesn’t love shouting “Help, I’m a Rock!”); “96 Tears” by ? and the Mysterians; Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band’s trippy, blues-laden Safe As Milk; Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction;” “(We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet” by the Blues Magoos; and Here Are The Sonics by the Sonics — just to name a select few.

Yet one band would rival them all, perhaps even put some of them to shame ─ regardless of whether they barely made commercial ripples.

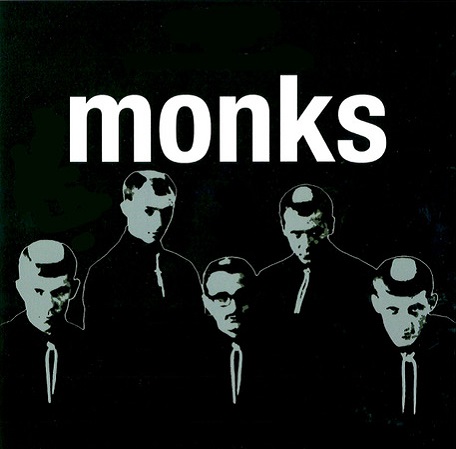

In March of 1966, The Monks’ lone studio masterpiece, Black Monk Time would be released on the Polydor label. Though the quintet included five Americans, it would be Germany where the group — Gary Burger (lead vocals and lead guitar), Larry Clark (organ), Eddie Shaw (bass), Dave Day (rhythm guitar), and Roger Johnston (drums) — would uncover its sound, look, and followers.

Though it’s not hyperbolic to say that the Monks are a fantastic precursor to punk rock (which started sprouting in the late 1960s), original member Eddie Shaw is a bit more subdued about the accolade.

“I could tell that we were sort of a precursor of (punk) because (those bands) did some of the things we were doing,” Shaw told me recently. “We didn’t concentrate so much on melody as we concentrated on the beat. The guitar, the banjo, the bass, the drums — everything had something to do with a beat more than a melody.”

Through Shaw, Nevada-based and now 85, I learned about the Monks’ intense road to notoriety. Think the Beatles’ humble leather-wearing, uppers-taking beginnings in Germany yet a bit more eccentric.

“We worked (in Germany) a year-and-a-half as the Torquays, which was a cover band. In a year-and-a-half we had three nights off; we were on stage six hours a night, six nights a week. On the seventh night, we were on stage eight hours a night,” Shaw recalls.

“We’d play one city in the afternoon, one city in the early evening, and one city late at night. Three different places every day,” he adds. “We did that for another year-and-a-half with about three to five days off. Finally, we got so tired that we finally just crashed.”

One look at photos of the band and you would think they were intentionally going for shock value, or perhaps giving the Residents some long-term ideas. To become “Monks,” they shaved their heads to look like the type of “monks” worthy of a Ken Follett historical novel. But, as Shaw describes, the look and aesthetic of the Monks “wasn’t inspired by anything in particular.”

“The haircuts were accidental. Roger was the first one to get his hair cut. We all had long hair and they cut his hair off. Roger said, ‘Cut a hole out of the top — give me a tonsure.’ I looked at it and the managers looked at it and they were aghast; they said, ‘That’s it, that’s what you got to do’,” he says. “So we did that and of course had our suits that we had custom made. The managers had the name Monks and they gave us the name Monks. We all determined it, but the managers suggested it.”

As the band built up its live presence and fanbase throughout Germany, the quintet would make simplicity a core focus of their sound. Don’t be fooled by the Monks’ freneticism, which could seem rudimentary on a first listen. Every note is carefully and intentionally played. Clark’s organ playing alone is a prototype for Ray Manzarek’s expansive soundscapes for the Doors (is it a coincidence their own debut album would be released in Summer 1966??).

“For us to write original material, we all agreed and worked on forgetting what our own prime interest was and simplifying things so we could come up with a unique sound that no one else had. We worked for a good three to six months doing that,” Shaw tells me. “Then we went to a studio, recorded a demo, and the demo was a little too radical. We toned it down a little bit and then Polydor agreed to record it and put it out in the market.”

The result would be the Monks one and only studio album — which comes in at just under 30 minutes (don’t tell me the Ramones never heard of this one!). Included in the book, 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die — which is how I first learned about it — Black Monk Time gets right to the point in a very direct way, exuding all the brash, in-your-face qualities that monks themselves aren’t known for possessing.

“(The album) took three days. The music sounds like it’s simple but it’s actually pretty complicated,” Shaw says. “What we did is we looked for tension. We learned in the clubs, playing in the clubs seven nights a week, that the tension is an important part to the music. So instead of doing 12 bars and eight bars, the regular progressions, we did 17 bars or 15 bars or odd counts and so forth. You had to be very careful to count them. That was the hardest part of playing that music was keeping track of the tension.”

In the 21st century, listeners can put this album on and take it completely seriously. But for 1966, you can’t help but wonder if the band is fucking with you or conveying some kind of joke we just don’t get. Even if you don’t probe the actual musical content, song titles like “Shut Up,” “Higgle-Dy-Piggle-Dy,” “I Hate You,” and “Drunken Maria” could leave you wondering how this was ever pressed onto vinyl. But the fun part is each track is an earworm — romps that could easily underscore the TV show Shindig!. Even as Burger all but shrieks, “You know I hate you with a passion, baby!,” your head inevitably bops along to the jangly beat.

I myself wondered if perhaps the irony and defiance exuded by the band carried over to Mr. Zappa and the Mothers when they set out to destroy Flower Power idealism on We’re Only In It For The Money. You have to pay attention to a band who sings the following right out of the gate in one unjumbled string:

“You know, we don’t like the Army; what Army? Who cares what Army? Why do you kill all those kids over there in Vietnam — mad Viet Cong; my brother died in Vietnam…”

For Shaw, the album’s attitude and lyrical direction were shaped by the unique crowds they encountered paying their dues in German clubs.

“We were immersed in this environment for a year-and-a-half — six hours a day mainly — where there’s drunks, there’s prostitutes; you’re dealing in a part of the world that most people don’t know about,” he says. “The words that we came up were what we were influenced by at the moment. I would say it’s a combination of American and German culture. Monks’ music is the result of the blending of two cultures.”

Though their sound is easily indicative of its time and not that different from other acts finding chart success in that period, Monks’ intensity, coupled with its collective look proved difficult for certain crowds to handle.

“At first, people were aghast. In Hamburg, you can see by the looks on the audience that people would not look us in the eye. We got used to walking around and never talking to anybody directly in the eyes because people thought we were real monks. We didn’t think of that,” Shaw says. “The further south we went — say the Catholic parts of the country — people there took issue with us. One night we got attacked on stage by a guy who rushed up on stage. Gary was singing, ‘I hate you,’ and some guy just rushed up on stage and was trying to yank the guitar out of his hand. I hit him with my bass. Security came out and took him away. We were always a little bit aware that anything could go wrong.”

Today, Black Monk Time is showered with accolades. Upon its release though, it landed not with a whimper but a thud stateside.

“Right away we found out we weren’t welcome in the states. They banned it. Every distributor refused to have anything to do with it. In the states, we were not recognized at all. But we hit number three with ‘Cuckoo’ [a later song not on this album] in Spain. We were in all the countries there; we played TV shows in different countries like Denmark and Sweden and all that. That was quite a bit different,” Shaw says.

Eighteen months after its release, the Monks would fracture and split. Per Shaw:

“The managers liked to play games with us and send us to strange places. One of the strange places they were going to send us to was Vietnam. We all had our visas and everything taken care of, ready to go. We met in Frankfurt at a restaurant early in the morning except Roger wasn’t there and Gary wasn’t there. The night before I received a letter from Gary saying I’m in the United States and I’m not going and Roger’s not going and that was the end of it. That was it.”

Monks reunions would ultimately take place decades later and the group’s legacy is easily assured after being included on the compilation boxset Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968. Sadly, Burger, Day, and Johnston have passed away, leaving Shaw as one of only two remaining members.

I closed our interview by asking Shaw his thoughts on how to best encapsulate what the Monks were all about and why they mattered in the pantheon of popular music. Yes, they were tongue-in-cheek; yes, they were funny-looking; yes, they weren’t necessarily accessible. But ultimately, they left a significant impact.

“I’d say, ‘I was a monk, you were a monk, we were all monks.’ We’re not monks anymore. I know what it feels like to be one. At the same time, I never was one,” Shaw tells me.

“I agreed to play the Monks’ music because it was also experimental. It wasn’t following the normal patterns that a lot of people do. It became a thing where playing outside the box, experimenting — that’s what I like,” he adds. “Even today I like brand new music that nobody’s ever heard before. It’s a new language.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.