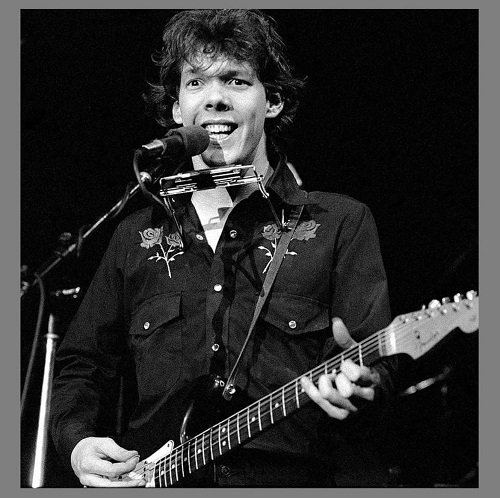

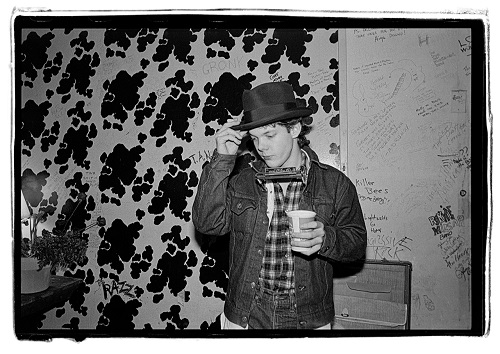

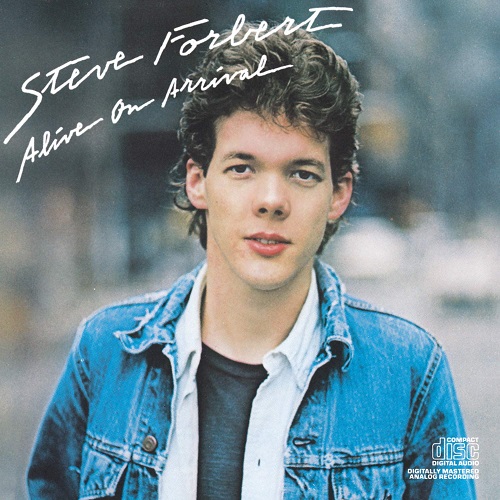

Photos courtesy of Steve Forbert

Between 1977 and 1978, at the height of the Bowery punk movement, a fresh-faced 22/23-year-old singing-songwriting Mississippian named Steve Forbert strove to make New York City his creative muse. The result yielded one of the more straight-from-the-heart — and underrated — folk-rock albums of all time.

Close to turning 45, Alive On Arrival melds the best stream of consciousness writing elements of Springsteen and Kerouac with Forbert’s own rugged, years-ahead-of-its-time voice. While the Ramones sang “Gimme, gimme shock treatment” and Richard Hell extolled the virtues of the “Blank Generation,” Forbert, with acoustic guitar and harmonica in tow, conveyed a different kind of storytelling — vivid and gritty; chock full of imagery that made his sojourn in the Big Apple one for the ages.

A native New Yorker myself, I recently caught up with Forbert who relayed how his debut was “deliberately” autobiographical, especially when it came to uncovering just what Manhattan was all about.

“I wanted that first record for me, if you will, [to be] ‘Kid comes to the city and this is what it was like,’” Forbert said during a recent lunch stop at Grossman’s Deli & Grill in Oakhurst, New Jersey. “When you look back at younger days, those songs came very easily. You’re falling in love with this girl; you’re getting your heart broken; you’re trying to hitchhike somewhere and you’re drunk. There’s just all kinds of input. The songs come pretty easily because you don’t have three kids and you’re not worried about health problems or anything like that.”

While Forbert executes an apparent ease when singing the songs on his debut, he’ll be the first to admit he could be his own worst critic back in those early days.

“I stressed about the [songwriting] craft in general a lot. That’s what I wanted to do. That was my top passion,” he said. “There were songs I wrote through those early times — I’d look at them and if I felt they weren’t good enough, I’d just throw them in the trash can or throw away the cassette tape. That was kind of a regiment I had.”

For Forbert’s fans, and especially readers of his noted autobiography Big City Cat, I’ll try not to rehash too much of what already exists out there about his career journey. But I do want to call out the highlights as they shape what ultimately turns into a five-decade career in music. Cutting his chops at venues like Folk City in Greenwich Village, Forbert would also take the plunge by infrequency performing in Grand Central Station. This would form the basis of one of Alive On Arrival’s greatest tracks, “Grand Central Station, March 18, 1977,” which contains the following lyrics:

“Well, think what you will, laugh if you like, it don’t make no difference to me. I’ll open my case, and I might catch a coin, but all ears may listen for free.”

“I probably only played there twice. You were not supposed to be in there, so it was risky. Just like the song says, ‘You better not stay here kid, the cops will get you.’ But you see I really was in a state where I needed the money,” Forbert told me. “It was winter and it was too cold to stand out on Lexington Avenue. So I said, ‘I’m going to try it.’ I don’t like singing in the subway because trains are coming and going and it’s so loud. But Grand Central Station itself — you could get inside that big cavernous space and you could kind of sing to the people on the move.”

Though gutsy, this move wouldn’t garner too many new fans for Forbert.

“Singing in the street is a real lesson in humility and it’s good practice because nobody owes you anything. Nobody arranged to be there to hear any music. They are on their way to or from work or something,” he said. “So you just sing for the experience of it to pick up a few bucks. But it’s not for the egomaniac because most people don’t even look at you.”

It would be the esteemed Bowery staple CBGB that would unintentionally provide Forbert with his ticket to stardom. He would soon hook up with managers Danny Fields and Linda Stein. Despite immersing himself in a shoebox environment known for its artistic angst, rapid-fire delivery, and intensity, Forbert describes the performing experience at CBGB as “pleasant.”

“The reality of it was [owner] Hilly [Kristal] liked me and the soundman Charlie Martin liked me, so they gave me a shot,” Forbert said. “They are not going to put me on at CBGB headlining on a Friday night. At that time, it was just me and my guitar, so they put me on as an opener for Talking Heads when they were a trio and, to my pleasant surprise, John Cale even. I was on stage and off in about 20 minutes and it was kind of like, ‘OK we got away with it. Would you like to try it again two Fridays from now…?’ I wasn’t really generating a fanbase, if you will, at CBGB but I was quote unquote discovered there so it all worked out.”

Though Forbert’s debut album contains several New York City-inspired songs, several also have their roots in the Magnolia State, including the frenetic “What Kinda Guy,” and the album’s dynamic opener “Goin’ Down to Laurel” (with one of my favorite lyrics: “It’s a dirty, stinking town…”). Yet it would Forbert immersing himself in New York City and its cast of characters to really get his creative fire burning. Examples include:

- The humble “Steve Forbert’s Midsummer Night’s Toast”: “When I got to the city and settled in and started meeting people and became familiar with Washington Square Park, for example, the song I had half written became a reality, which was a nice surprise. I just finished it with what was real-time actual experience.”

- The adrenalized and confident “Big City Cat”: “That was a completely accurate description of living in an apartment on East 4th Street right there on the Bowery and stuff. That’s kind of what you would be hearing and seeing.”

- The somber “Tonight I Feel So Far Away From Home”: “That’s a first winter in New York City song. I was living that.”

- The rollicking “You Cannot Win If You Do Not Play”: “I just got drunk one night and decided I was going to hitchhike to Pennsylvania. I failed and I kind of came to and realized that I didn’t know really where I was going or where I was. So I hitchhiked back to the city and just in a burst of sort of like shock or embarrassment, I wrote “You Cannot Win If You Do Not Play.” I had made some notes for that song when I was hitchhiking, which is a good place to write songs because you’re by yourself, you’re in the middle of nowhere, and you can think.”

- The sweet “Settle Down”: “That was written in real-time as part of the experience for having moved to New York City. “Settle Down” was kind of a love song and an apology for being so crazy, so impetuous, if you will, or so impulsive.”

Forbert would ultimately land a record deal with jazz and pop label Nemperor Records, bonding closely with founder Nat Weiss. Sessions for Alive On Arrival would last approximately four weeks as Forbert fights to keep his tracks as “live” as possible.

“Some of it was very difficult because I said I didn’t want any overdubs: ‘We’re going to record this fucker totally live. And I don’t want any reverb,’” Forbert says. “So I had people resisting me and trying to change me a bit. It was not a piece of cake. But I got what I wanted. It was a bit of a battle for me to keep the rule going of, ‘No, I’m not going to overdub that part; no, can’t fix that mistake.’”

Regarding the album’s production, Forbert would take the feedback of one person to heart — Bonnie Raitt.

“She just said, ‘The record’s too dry. You gotta add some reverb,’” he said. “I was pretty paranoid, especially making the first record, because I didn’t want to be controlled into something that I wasn’t trying to present. One of my things was I don’t want a bunch of reverb on this record … In truth, I didn’t know what I was talking about; I was just being precautious. When they told me that, I was like, ‘Oh I guess I better.’ We were all better off for it because it sounded more like a record.”

“The engineer and the producer were relieved — like, ‘Yeah, let’s remix it. We’ll be glad to start tonight!’,” Forbert adds.

While the album and being hailed as a “new Dylan” would help Forbert acquire bigger audiences and exposure, he says the latter was not something he was ready to completely embody.

“You know it’s going to happen; I wasn’t like shocked. I couldn’t just say, ‘You guys are crazy; don’t say that anymore. Excuse me and I’ll take off this harmonica and put down this acoustic guitar, let’s not say that anymore.’ But the thing is I did have to resist it,” he says. “I didn’t want to just be some lunatic that’s like, ‘Yeah, I’m on that boat, I’m on that train.’ That would be daft.”

From this release comes the global acclaim; the Top 20 major league single with “Romeo’s Tune;” the appearance in Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” music video; the releasing of more albums; the switching of record labels; the Grammy attention; and so on. All of this culminates now in Forbert’s 23rd album, Moving Through America, released on the Blue Rose label. Unlike the early days of his career, the songs on this album were written over a four-year period.

Here, Forbert’s songwriting gets a bit peppier, even funkier in spots. There’s the Beach Boys-esque “Palo Alto,” the twangy “Buffalo Nickel,” and the groove-laden “Please Don’t Eat The Daisies” and “It’s Too Bad (You Super Freak).” Here, listeners will uncover great pastiches of America as Forbert shifts his songwriting to reflect what he’s seeing as a third party, versus having the focus just be on him.

“As you get older, you get more like Tom Waits maybe or Bruce Springsteen, if you’re going to keep writing songs, they’re going to be more observational, and it might be less first-person/first-experience,”

he says. “Let’s face it — you’ve kind of been around the block a few times. This is just what comes for me when writing songs, is writing interesting observations about situations.”

Though it’s not formally dubbed a concept album, Forbert’s America depicted here is well worth the trip, whether we partake of “Fried Oysters” or make a stop in Gainesville, Florida to pay respect to the late Tom Petty (“Say Hello to Gainesville”).

“I wanted this to be the best record I could make. I really do get around a lot in this country and I do care about the next hurricane in Houston. It kind of almost appears to be a concept album because it’s write what you know,” Forbert says. “That’s what I know — these things I focus on in the United States.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s new book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.