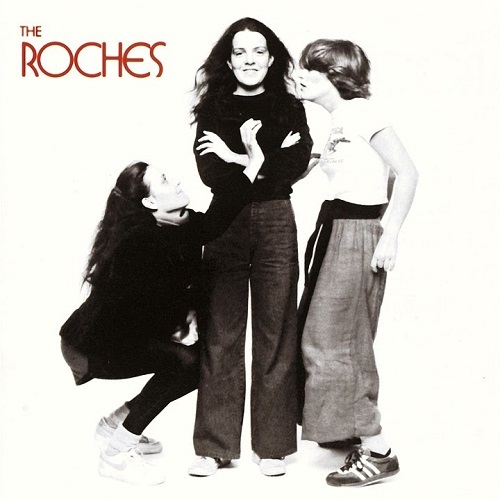

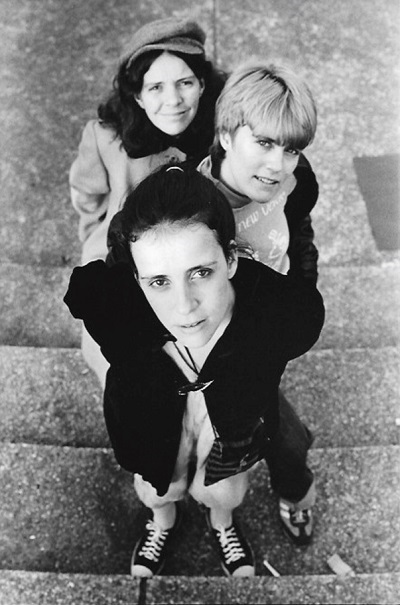

Photos courtesy of Terre and Suzzy Roche

Forty years ago, guitar legend Robert Fripp unveiled two of his most unique album efforts — neither of which bared the King Crimson label.

First, in April of 1979, came the eponymous debut album from trio sister act The Roches. Sparse in its production, content and execution, Fripp would serve as producer and contributing musician for the album — marking a complete about face stylistically from such efforts as Larks Tongues in Aspic and Red. Then, two months later, Fripp would release his debut solo album Exposure, an artsy, brooding work, reflecting New York City in all its permutations and setting the precedent for 80s era Crimson featuring the enigmatic, bespectacled leader alongside Adrian Belew, Bill Bruford, and Tony Levin.

While these two releases are diametrically opposed, they serve as important benchmarks to the legacy of Fripp as innovator and musical visionary. Though The Roches wouldn’t make Maggie, Suzzy and Terre Roche music superstars, they would become critics’ favorites. New York Times journalist John Rockwell called their debut “so superior that it will be remarkable if another disk comes along to supplant it as best album of the year.”

The relationship between Fripp and the Roche sisters began when the former caught the trio singing in Greenwich Village clubs. Terre Roche told me recently when she first met Robert Fripp she had no idea what King Crimson sounded like; she only knew the cover of In The Court Of The Crimson King.

“That’s as much as I knew about Robert Fripp was that album cover,” she said. “I didn’t even really know the music.”

Taking up residence in New York City, Fripp had been approached by Warner Brothers to produce an act. He chose The Roches.

“Everyone was surprised that he was interested in this type of music. I guess they figured he’d bring them something that was electric. This was three voices and three acoustic guitars,” Terre told me. “So that was surprising. We all hit it off and we all felt this was a good match.”

Though he is likely best known for his studio wizardry and intricacy when it comes to musical output, Fripp’s direction for the sisters — two of whom (Maggie and Terre) got their start backing Paul Simon before trying to make it on their own — was minimal at best.

“We went into the studio and sat around in a circle and played. I think he came up with the idea of recording us with no reverb, which gave the record an interesting, unusual sound. But other than that, he left us alone,” said Terre’s sister Suzzy.

“I would have to say that he didn’t give us any direction. What he wanted us to do was what he saw and heard us do in the club,” Terre adds. “Some of the songs on that record were actually live takes. Maybe at most you do three takes. We were very well-rehearsed. We had these arrangements that had already been arranged and he didn’t want to change it into something else. I remember he said he felt the sign of a good producer was that you didn’t even notice the production.”

All together quirky, introspective and self-deprecating, the Roches eschewed overhyped production to convey songs of whimsy and well-being. The album is a hodgepodge of whimsy and tight harmony, especially on standout tracks like “Mr. Sellack,” “The Troubles,” “Quitting Time,” and “Hammond Song.”

Thanks to Fripp’s no-frills mentality, the album ultimately came in at a third of its overall $100,000 recording budget.

“I remember being sort of proud of that,” Terre said. “Robert Fripp actually had a record of his own called No Pussyfooting and that was a big part of his philosophy. You don’t fart around in the studio with stuff. You go in and you do it. I really liked that approach.”

The album’s greatest track, “Hammond Song,” reflects a time when Maggie and Terre, recording and performing as a duo, played three shows behind their 1975 duo Columbia album Seductive Reasoning before quitting the music business to move to Hammond, Louisiana, and live in a friend’s Kung Fu temple. The song also highlights — albeit briefly — Fripp’s intricate playing, which sounds somewhat similar to the classic Crimson track “Starless.”

“We talked him into playing guitar on it. He was tuning his guitar up and Ed Sprigg, the engineer, knew that he should roll tape. That tuning up is what went on the record,” Terre said. “What happened was I think he maybe did another two takes and we all agreed that first thing when he was warming up was the one.”

“We talked him into playing guitar on it. He was tuning his guitar up and Ed Sprigg, the engineer, knew that he should roll tape. That tuning up is what went on the record,” Terre said. “What happened was I think he maybe did another two takes and we all agreed that first thing when he was warming up was the one.”

Adds Suzzy Roche about the album’s collective instrumental output: “The arrangements were set. Robert played that great guitar part on ‘Hammond Song,’ and brought in Tony Levin to play bass on ‘Hammond and ‘Quitting Time,’ and Bill Bruford to play some percussion parts. Larry Fast came in and did some very minimal synth parts. Other than that, the arrangements were what we had played live.”

Signed to Warner Brothers at the same time as Talking Heads and Rickie Lee Jones, Terre Roche still marvels at how, with their minimal debut, the group garnered fans in singers like Linda Ronstadt and Phoebe Snow and managed to survive in a tough music business.

“That was really surprising to everybody at the time because it didn’t get on the radio. It wouldn’t get played on the radio because of the formatting. We didn’t have bass and drums, the kind of pop sound,” she said. “It was a very male-dominated time in music. I think we were swimming upstream. We were three female voices with three guitars that we were playing. Hats off to Robert that he saw something in that that he wanted to foster that.”

Terre adds one element best defines Fripp that would carry over to his future work (solo and Crimson-wise) — total adherence to discipline.

“We each influenced each other. I think we kind of pulled him into this scene of staying up all night and hanging out and he pulled us pretty hard into the discipline thing,” she said. “I took guitar lessons with him while we were working on the records that we worked on and that was all about discipline. It was very difficult for me and I really had to focus.”

Robert Fripp’s Exposure is an iconic album in the greatest sense of the word. From the moment Brian Eno utters the classic line, “Can I play you some of the new things I’ve been doing which I think could be commercial…” to open the release, you know you’re going to hear something very different — a pastiche of gritty, evocative tracks entirely intense and emotive at the same time.

Robert Fripp’s Exposure is an iconic album in the greatest sense of the word. From the moment Brian Eno utters the classic line, “Can I play you some of the new things I’ve been doing which I think could be commercial…” to open the release, you know you’re going to hear something very different — a pastiche of gritty, evocative tracks entirely intense and emotive at the same time.

Begun in June 1977, the album showcases several unique elements, including the following:

- Daryl’s Hall most unique vocal output prior to his becoming a superstar in the 1980s (just listen to the 1950s sounding “You Burn Me Up I’m a Cigarette”).

- The emergence of Peter Gabriel as a solo superstar with a pared down “Here Comes the Flood.”

- Sounds reflecting King Crimson’s imminent, tightly packed musical future as demonstrated by the album trio of Discipline, Beat, and Three of a Perfect Pair. It’s hard not to listen to this album and think of “Matte Kudasai” or “Thela Hun Ginjeet.”

- Brian Eno’s continued influence; this album should be considered a forerunner to Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, his fantastic, sample-fueled album with Talking Head David Byrne.

- The inclusion of Terre Roche as sole female vocalist.

On Exposure, Terre Roche joins ranks with the boys club of Hall, Gabriel and Peter Hamill (Van de Graf Generator). Hall initially served as primary vocalist but once his record company limited him in how many tracks he could appear on, Terre stepped in to bring a newfound dynamism to “Mary,” “I May Not Have Had Enough of Me but I’ve Had Enough of You,” and the album’s title track.

Updated releases of Exposure showcase Hall’s own takes on “Mary” and “Exposure.” They’re well worth a listen, especially given that Fripp would produce Hall’s first solo album Sacred Songs.

“I May…” proved to be a spontaneous burst of verbal creativity and sparring between Hamill and Roche.

“Fripp gave us the lyrics. We had never met. Peter Hamill and I were facing each other and we each have a microphone and we each have a lyric sheet. We hadn’t heard the track and what Fripp wanted us to do was listen to the track and trade lines. The only instruction we had was that, ‘You’re going to do the next line;’ ‘You’re going to do the next line,’” Terre told me. “We had to find whatever the melody we were going to use and just interact with music, having never heard the music. So that was interesting because that was completely improvised. It was a No Pussyfooting, as I remember, especially that. I think that was a one take situation.”

Meanwhile, “Exposure” proved a challenge. The track features a rolling, repeating guitar melody that moves down the neck in sounds. Penned by Gabriel, the track also features a distinctive sampled background vocal: “It is impossible to achieve the aim without suffering.” One can argue Roche lived up to this as her voice is literally stretched to its breaking point.

“It was almost like (Fripp) kept wanting me to go farther into the primal screaming area as we worked on it. I remember doing many takes of that one because of this idea that he wanted me to go further,” she said. “He didn’t want there to be any politeness about it.”

Roche makes it clear the vocal you hear is not hers entirely as Fripp’s production expertise would elongate her voice to make it sound as if sustaining for several seconds. The album’s liner notes indicate her voice had been “fritched.”

“I picked up a whole bunch of a cult following from that track. People are surprised when they hear it that it was me that sang it,” Terre says. “We’d get people coming backstage and you could almost tell by the look in their eyes they wanted to shake my hand about ‘Exposure.’”

The Roches would perform in various incarnations until 2017. Sister Maggie Roche would pass away that year at the age of 65.

“The Roches existed before the Internet, so there is very little video of us, which is sad because our live shows were great. I think we influenced many people, which makes me feel good (as) we were one of the first all-female bands,” Suzzy Roche says. “Sometimes people mistake us for a “novelty band” because we were multi-layered and different but I think if people are interested in knowing about the depth of our music, the collection of Maggie’s songs Where Do I Come From is a wonderful place to start. Maggie was really the heart and soul of the group.”

Fripp would go on to produce the group’s third album Keep on Doing (1982). For Terre Roche, she looks back fondly on her time with the prog rock stalwart, stressing that while The Roches never contributed much commercially to music, just having the attention of a musician of Fripp’s stature proves good enough.

“It would have been great if ‘The Hammond Song’ was playing in the supermarket because that would have meant that all of us would be able to buy a house and have health insurance. Success would have been great. But…I guess we weren’t that ambitious toward it, or maybe we just didn’t know how to write those kinds of songs,” she says. “I’d rather look back and be proud of the work than have a yacht at this point in my life.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.