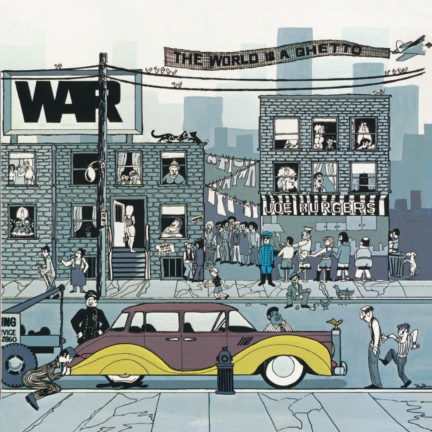

Fifty years ago, one of music’s greatest melting pot collectives released their masterpiece.

The World Is A Ghetto by War is a seminal six-track work that told it like it was with a consciousness and universal understanding that still resonates today. It’s unbridled funk with pointed and direct messages. Soul with heart. You can groove to it but it’s even more important to listen to it. Within the album’s songs, you get detailed depictions of street life, the minds of the downtrodden and lay people, and raw emotions from populations trying to essentially claw themselves out of the muck.

This album became a standout staple for me during the COVID-19 pandemic as there’s a shared connectivity between the isolation conveyed on certain tracks and the isolation we all felt worldwide trying to stay safe and healthy in uncertain times — even if we couldn’t always control the circumstances. Simply put, this is an album that should be in the pantheon of classics like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. It would prove that the seven-piece War (with members hailing from different parts of the globe) was in fact a peoples’ band — one of music’s greatest social commentators, offering up an equal balance of melody and life lessons.

If that isn’t enough, The World Is a Ghetto would wind up being the biggest selling album of 1973.

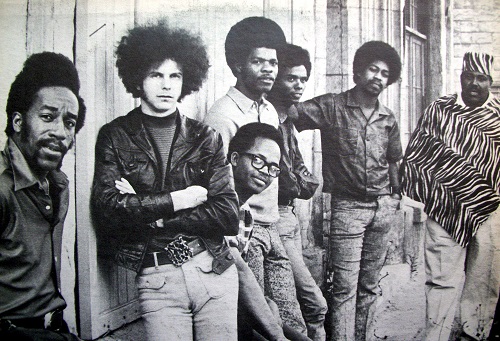

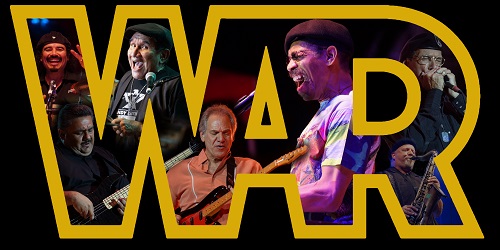

Where War members Lonnie Jordan (lead vocals and keyboards), Howard E. Scott (guitar), B.B. Dickerson (bass), Lee Oskar (harmonica), Charles Miller (saxophone), Thomas “Papa Dee” Allen (percussion), and Harold Brown (drums) would make their initial fame backing up British Animal Eric Burdon (who doesn’t know and savor the lyrical phrase “Spill the wine, take that pearl”?), this album would be the one that set the group on a trajectory to superstardom — which has since culminated in multiple appearances on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ballot.

“When we got with Eric Burdon, before we ever really did our first rehearsals or even our first shows, we’d sit up there in Laurel Canyon with all the hippies and all he did was play different music to us from the blues genre. Then he’d play rock. And we’d listen – we spent about three or four months just listening before we ever really started creating music,” Harold Brown told me. “So when we got into the studio, he taught us how to create. When we did The World Is A Ghetto, we went in and all of us would sit and start writing … We would sit and discuss things of what we were seeing. We’d make a track and we would start talking about things that were in our heads, you know.”

The hypnotic, sensual “Spill The Wine” would become War’s first major hit, peaking at Number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1970. The next year, with the release of their album All Day Music, the group would land another couple of tracks in the Top 40, the title track and the sly, funky “Slippin’ Into Darkness.” The latter would go on to be one of the most sampled tracks in rap and hip-hop.

“Most black bands…sounded like [they were] from Detroit or from doo-wop,” Brown said. “We were taking a different trail because “Slippin’ Into Darkness,’ when they broke that, it was way different from everything else that was out there.”

For Ghetto, War’s fifth album, a new array of influences would spark its creation: the neighboring streets and chameleon-like surroundings outside of Los Angeles; the apparent yin-yang of wealth and poverty; and the connective thread of multiculturalism included.

“That’s where we started realizing the world was a lot more than what we thought. We had a saying, ‘Little money, little problems; big money, big problems; no money, problems, problems,’” Brown told me. “So we started out hanging out around Beverly Hills and Malibu where all the superstars and everybody were hanging and living. We started noticing that they had the same problems like you’d have in the inner city. The toilets would back up. They have flat tires even if they were driving a Rolls Royce or whatever. And that’s when Papa Dee came up with that concept — ‘The world is a ghetto.’ We could see that there was a lot of different things that all of us were dealing with, issues that made the world a ghetto and how you looked at it and where you were at.”

The album’s title track, even with its bleak lyrical undertones, would peak at Number 7 on the Hot 100. Unlike other commercial hits from that year, “The World Is A Ghetto” is explicit in its explorations of societal and inner-city consciousness:

“Walkin’ down the street, smoggy-eyed…

Looking at the sky, starry-eyed…

Searchin’ for the place, weary-eyed…

Crying in the night, teary-eyed.”

“When we were doing ‘The World Is A Ghetto,’ that one was more on the basis of an arrangement. Papa Dee was trained in classical music. He was about 10, 15 years older than me. He was more classical thinking. B.B. Dickerson was the best crooner of the group – he sang lead on it,” Brown recalled. “When we wanted to sing “The world is a ghetto, that’s when we went to the B part — it was an A part, B part, and C part and then back. It was more of an arrangement. That was not so much of a jam; we knew that there were certain parts that we had to hit to make that turnaround.”

Yet even though the group’s music was leaning more towards the realness of the world, band member chemistry would ensure the album’s tracks contained the right doses of accessibility in tandem. Case in point, album opener and the group’s biggest single hit — the colloquialism-fueled, groove-laden tune “The Cisco Kid.”

“’The Cisco Kid’ was the only non-European or non-white hero on television that we would see as kids that we could kind of relate to — because he wasn’t Superman or something,” Brown said.

“In those days, when we went into the studio, I loved it. We would rent the studio for a couple of weeks,” Brown adds. “What was really good was they would go in and set it up like we felt at home when we were inside the studio. Inside, the studio was set up so we could see and communicate with each other. There was a lot of songs that were jams.”

Then there are album tracks that highlight the group’s instrumental prowess. “City, Country, City” would take listeners on a journey that shifts from one of imagined traffic and congestion to one of wide-open pastures and then back again. The progression would shift from funk to soft soul, and then back to funk once again.

“Four Cornered Room,” meanwhile speaks more to isolation and the pathways the mind travels when left to confront one’s own thoughts (hence the repeated lyrical refrain of “Zoom, zoom, zoom!”).

“I remember we just started doing it. I was living up in Silver Lake, California outside of Hollywood. And I had my four-cornered room,” Brown recalled. “You couldn’t afford the big old rent up there, so I had me a little studio apartment. I had a small refrigerator with a microwave on top … and [I’m] sitting there and reflecting in my four-cornered room like we’re all doing now.”

Eventually, according to Brown, touring in support of their music would make the reality of the album’s key themes that much more apparent.

“When we finally went to Denmark, I could see certain things that we could relate to or if you go to Great Britain ─ homeless people sleeping in an alley. You’d start seeing it when we were traveling,” Brown said. “When we went to New York, or if we traveled to Atlanta or New Orleans, we could see the world had its ghettos.”

War would go on to have continued commercial success throughout the 1970s with peppier tracks like “Gypsy Man” and “Low Rider” as well as albums like Deliver the Word and Why Can’t We Be Friends?. The latter album’s title track and its reggae-stylings would speak to collective solidarity and brotherhood. However, over the years, little by little, band dynamics would start to fray, culminating in a group breakup in the 1980s.

Though different band factions exist today — one helmed by Jordan and another dubbed The Lowrider Band featuring Brown, Oskar, and other members — there remains the potential for the group’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (the third time could be the charm!) and perhaps a group performance bringing all surviving members back together.

Either way, it’s important to remember how with their mastery of global themes and unique musical stylings, War would, at least for a period of time, outsell other Hall of Fame groups ─ Chicago, The Moody Blues, and Cat Stevens included. Per Brown, the themes conveyed on The World Is A Ghetto hold just as much relevance in the modern 21st century. The question becomes, what, if anything, needs to be changed?

“Change it from being the world is a ghetto; we can make the world be more heavenly or better or something. We can’t just run. If you leave it’s not going to make it better,” he says. “While you’re there, use what you got to help make it better.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s new book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.