By Shawn Perry

There is no question that Jethro Tull has weathered any number of trends, trials, tribulations and testaments over the course of 50 plus years. This is because Ian Anderson — the band’s sole original member, songwriter, singer, flautist, mascot, and ostensible leader — tends to keep things running consistently and smoothly with little deviation from the formula. Despite nearly 40 different musicians coming and going within the ranks, it’s always been Ian Anderson front and center, carrying the banner year after year.

Then 2020 came along and put the world on hold, thanks to a nasty virus. Even Ian Anderson, who spends much of his time traveling between Europe and the United States playing the music of Jethro Tull, was dealt a major blow. And with the reoccurrence of variants causing shutdowns in regions around the world, it’s not going to get any easier for touring musicians.

“I think there was a main feeling of dissatisfaction that came from planning tours and doing all the work of building tour itineraries, checking flights, hotels, putting everything into place — only to find then you had to do it all over again,” Anderson tells me over a Skype call. “Every day, I’m having to look at itineraries and make changes or consider where we can move concerts to when promoters are getting worried. So we’re kind of back where we were really in 2020. We have to be optimistic and hope that things will improve in the months to come. It is depressing, but it’s not going to ruin my life because I have other stuff to be doing.”

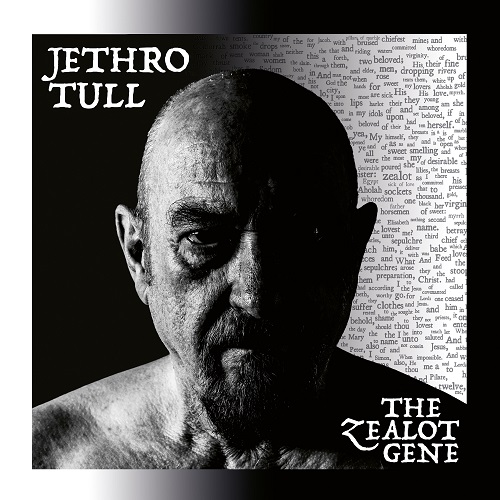

Without a road to travel on, Anderson does indeed know how to stay busy and productive. When he’s not overseeing retrospectives around Jethro Tull, he’s writing and recording new music. The result is a new album for 2022 called The Zealot Gene. Most surprisingly, it’s not Ian Anderson’s third solo album in the last 10 years — it is, instead, Jethro Tull’s first new studio album in nearly 20 years. Which begs the question: Is there a difference?

To completely understand, you have to go back to 2011 when Jethro Tull were touring behind the 40th anniversary of Aqualung, arguably the band’s most popular album. At the tour’s end, Anderson decided to put the brakes on Jethro Tull. Well sorta. As he told me in 2012, he was experiencing what he called a “Roger Waters moment” — seeking recognition under his name with a wink to the band he’ll be forever anchored. Waters can’t shake off Pink Floyd, and the same goes for Anderson and Jethro Tull. Even more so. The singer as a wild-eyed, one-legged flautist wearing a codpiece is part of the band’s logo! You’ll never hear: “By the way, which one’s Jethro?” That’s because it’s always been Ian Anderson.

He had tried to go solo before. First in 1983 with Walk Into Light, then again in 1995 with Divinities: Twelve Dances with God, which he supported with a handful of shows. In the early 2000s, he ventured solo with two more albums —2000’s The Secret Language Of Birds and 2003’s Rupi’s Dance. More touring followed, culminating in such ill-conceived experiments as the Rubbing Elbows format in which Anderson transformed himself into a talk show host.

Those four albums were intended departures — stylistically enough to merit solo status, even though some of the musicians were in Jethro Tull. The shows behind those albums also featured a fair amount of Jethro Tull music. There’s simply no way of getting around it if you’re Ian Anderson.

It’s hard to gauge what his intentions were when he decided to give Martin Barre — Tull’s guitarist since 1969 — and longtime drummer Doane Perry their walking papers. The idea of Jethro Tull would carry on, of course, and certainly Anderson, as the leader, had every right to harness the “Jethro Tull” name in any which way he wanted. So for his first solo album after “breaking up” Jethro Tull, Anderson released a sequel to Jethro Tull’s 1972 landmark concept album, Thick As A Brick. Entitled, in the parlance of the times, TAAB2, the album’s artwork and liner notes liberally sprinkle in the Jethro Tull name. The music also has a very Tullian feel. Longtime observers are either impressed or annoyed — perhaps a mix of both — with TAAB2.

The next album, 2014’s Homo Erraticus, is even more Tullian than its predecessor. The lyrics are even credited to Gerald Bostock, the fictional protagonist in Thick As A Brick. Anderson admits it should have been a Jethro Tull album. “It was very much a band album with the guys who’d been playing with me already for many years,” he says. “They’re the same guys who were on The Zealot Gene. So they deserve their time to be on a Jethro Tull album as opposed to an Ian Anderson album.”

Anderson is quick to remind me that musically, The Zealot Gene is very much in the progressive rock style and breadth of Jethro Tull’s music. Which makes sense because Anderson has always maintained Jethro Tull is more about repertoire than its members. “I think it earns serious consideration as being a Jethro Tull album just as if I go on tour and perform in a concert almost all or completely all Jethro Tull repertoire as recorded originally, then I call it a Jethro Tull concert.”

The rest of the band — Joe Parrish-James and Florian Opahle (only in the studio) on guitars, Scott Hammond on drums, John O’Hara on piano, keyboards and accordion, and David Goodier on bass — worked closely with Anderson early on in the development of the album, gaining their Tull stripes. Once the pandemic kicked in and everyone scattered into quarantine, Anderson was on his own, recording acoustic numbers like “Jacob’s Tales,” “Three Loves, Three” and “In Brief Visitation” at his home studio.

As for its theme and form, The Zealot Gene definitely meets the criteria head-on. Anderson gives me the lowdown on how the plot unfolds. “I started off with the idea that I would write a series of songs, each one about a different, powerful human emotion. I began making a list of words, single words that describe strong emotions, like anger, greed, vengeance, jealousy and some nice stuff like love, fraternal love, erotic love, spiritual love, companionship, loyalty, compassion. I looked at my list of words and I thought: ‘All those words feature prominently in the King James English translation of the Bible.’”

From there, Anderson presented the songs in present-day scenarios that illustrate contemporary examples of the emotions he wrote down. Just as Aqualung, 50 years earlier, questions religion and God, The Zealot Gene pushes further inquiries into how the certain emotions spelled out in the Bible play into modern-day avarice and propaganda perpetuating a divisive world gone mad. “Carrying the Zealot gene,” the chorus to the title track goes, “right or left, no in between.”

Though he expresses no overt bias, it’s not difficult to figure out where the political pendulum swings with Anderson. He is, however, more forthright in his spiritual views. “I’m not a practicing Christian. I’m a huge supporter of Christianity in a very real sense of my work for the church every year. But I don’t call myself a Christian because I am somewhat of a rather broader set of slightly shifting and changing beliefs.”

Then it’s down to specifics. ”You could probably put me down as being more of a pantheist belief kind of guy. Maybe deist,” Anderson ponders. “I still have a huge appreciation for the Bible and the storytelling. The narrative of Christianity is compelling because unlike most other religions, it tells a story. It has a beginning, a middle and an end. And it has a particularly dramatic ending, too. When you put the whole Bible idea together, it leaves you with the prophecy of a Netflix season three, somewhere on the horizon. Christians have been waiting for 2000 years for season three, and it hasn’t come yet, but never give up hope. We’ve got season four of Ozark to look forward to in the meantime.”

To give The Zealot Gene concept a visual medium, there are three music videos on YouTube making the rounds. The first single, “Shoshana Sleeping,” is accompanied by a stunning black and white visual created by Thomas Hicks. Sam Chegini was then enlisted to direct music videos behind “Sad City Sisters” and “The Zealot Gene.” The award-winning director, animator, and puppeteer has made a name for himself in progressive rock circles creating videos for Jakko Jakszyk of King Crimson and Gentle Giant. In 2021, he was brought on to develop an animated video around “Aqualung” to celebrate its 50th anniversary.

Interestingly enough, when it comes to the videos — spilling over with eye-catching, surreal images dancing around motifs and allegory — Anderson takes a decidedly hands-off approach. Working with someone like Chegini — an Iranian citizen, presumably living in Tehran, making music videos for Western artists on the sly during a pandemic — comes with certain risks, the least of which is a close collaboration.

“I see his storyboards and we loosely talk about it,” Anderson says. “But I don’t want to interfere in his creative process. His vision of what a song means is completely different to mine and possibly different to many other people too. I think that’s the validity of being a listener — you form your own impressions about a song and what it means to you. It doesn’t necessarily echo precisely what it meant to the composer or author of the lyrics. So I would rather give him the right to make a video that reflects what he thinks it means to him. If that doesn’t strongly disagree with my own thoughts, then I’ll go along with it. But at the end of the day, this is about marketing and promotion.”

The next logical step is touring — something that’s become a challenge since the beginning of 2020. Anderson and the other current members of Jethro Tull spent most of that year and over half of 2021 off the road. From August through December, they played a handful of dates in Europe. The shows were billed as “Ian Anderson presents Jethro Tull – The Prog Years,” which meant the line between Anderson’s solo career and the band he couldn’t let go of was slowly fading. The focus was squarely on Jethro Tull, with glimpses here and there of The Zealot Gene, just to let everyone know something’s cooking in the oven.

When news of the Omicron variant hit in late 2021, Anderson and company pressed on through the holidays, playing a round of annual Christmas concerts at three British cathedrals. “We managed to do 20 concerts last year,” Anderson remarks without reservation. “Nobody got COVID, but we were being very, very careful, testing every 48 hours and being very careful about our social bubble that we tried to remain in.”

The first “official” Jethro Tull tour in over 10 years is scheduled to open on February 5th in Varese, Italy. Even though Anderson told me he was scrambling to move things around, the shows are still scheduled to take place. Like everything these days, that is subject to change.

Meanwhile, Ian Anderson stands at the crosshairs of his past, present and future. He continues to look back with a consistent roll-out of reissues and two books — the biographical Ballad Of Jethro Tull and Silent Singing, a collection of his lyrics. And now with Jethro Tull reassembled as an actual band, he’s entering a new era.

With The Zealot Gene in his rearview mirror, Anderson’s already at work on the next Jethro Tull release, which he began on January 1st. “I’m 12 days into writing a new album,” he exclaims proudly. “I spend a couple of hours a day working on that and that’s going to keep me fairly occupied for this month and probably the next month as well when I present the band with some demos and we start looking at some options for rehearsal and recording.”

Still, some longtime followers question the legitimacy of Jethro Tull and The Zealot Gene without certain former members — namely Martin Barre. How does Anderson respond to that?

“Martin Barre wasn’t in the band when we got together in 1968,” he’s quick to note, eloquently adding: “Of course, he was a hugely important member of the band. But he wasn’t the guy writing the music, producing the records or, on the more pragmatic and practical side, effectively running Jethro Tull as a business. I took on the responsibilities and the risks back in 1974. I produced and was paid for producing the records from 72 onwards. I was taking on a much greater mantle of responsibility for the end product, but I couldn’t have done it without (any of) them. We are all part of an extended family of some 27 musicians who’ve been in and out of Jethro Tull over the years.”

Though he hasn’t been in contact with Barre since parting ways, he does stay in touch with other former Jethro Tull members. He talks regularly to Jeffrey Hammond-Hammond, a friend since they were both teenagers in Blackpool. Hammond served as the band’s bassist from 1971 through 1975, and was the inspiration for three songs — “A Song for Jeffrey,” “Jeffrey Goes To Leicester Square” and “For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me” — recorded before he even joined Jethro Tull. He may be best remembered as the narrator of “The Story Of The Hare Who Lost His Spectacles,” a surreal, Alice in Wonderland type spoof from A Passion Play in which he received a rare writing credit. The bassist who turned to painting after leaving Tull is someone, according to Anderson, who’s suffered from a number of health issues in recent years.

As for others who were, at one time or another, a member of Jethro Tull, Anderson addresses it without prejudice: “There’s nobody teetering on the edge of life and death at this moment, as far as I know. Doubtless at our age, there will be increasingly the likelihood that there will be another Jethro Tull member who will pass away. And that will be a dark day.”

He takes a breath, then laughs nervously: “Especially if it’s me.”