By Ira Kantor

Photos Courtesy Chapin Productions LLC

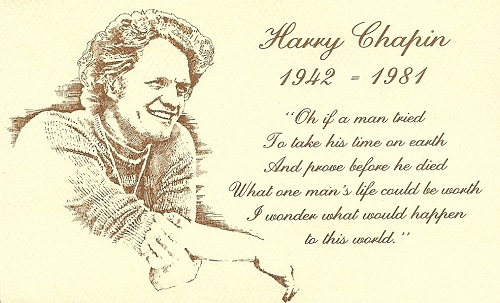

The life of Harry Chapin, charismatic musician and iconic humanitarian, was unexpectedly and tragically taken on July 16, 1981. He was 38 years old.

A human dynamo whose sheer tenacity landed him on the Billboard charts, on Broadway, in the White House, and at the forefront of the world hunger movement, Chapin lived by the mantra of “When in doubt, do something.” In following this mentality, Chapin’s 10-year solo career encompassed more than 2,000 concerts, nine studio albums, the creation of global nonprofit World Hunger Year (now WhyHunger) and the love and respect of fans, fellow musicians and key political influencers alike.

Hailed as a consummate musical storyteller, Chapin is best known for his character-driven tunes —“Taxi,” “Sniper,” “W-O-L-D,” “A Better Place to Be,” “30,000 Pounds of Bananas” and “Cat’s in the Cradle” included. Yet despite having only four Top 40 hits to his name, Chapin’s songs remain one of a kind — elevating him to the same artistic status as classic singer-songwriters of the era like James Taylor, Jim Croce, Gordon Lightfoot and John Denver.

Nearly 40 years after his death, the following 10-part oral history seeks to tell Harry Chapin’s story through the firsthand, on-the-record testimonies of the “characters” who knew him best – more than 50 family members, friends, business and political associates and musical contemporaries. For added context, Harry’s own voice, along with other relevant news articles and reviews during his lifetime, are included in italics.

While there are other individuals and events crucial to Harry’s tale who were unable to be interviewed or showcased for this series, this still seeks to provide a well-rounded retrospective of a man whose life, being, sense of accomplishment and legacy remain unsurpassed to this day.

***

Chapter X

I WONDER WHAT WOULD HAPPEN TO THIS WORLD

Anthony Curto (Friend, Attorney): Harry died literally without any money except for an insurance policy that was made to World Hunger Year, the charitable organization. So, for all intents and purposes the family was not destitute, but without any funds. The only money that they really had was wrapped up in the lawsuit for the wrongful death case.

Sandy Chapin (Wife): I was definitely a different person. I’m pretty much a homebody and I remember that I would find something to do, some place to go like every evening. I mean eventually I got really depressed and I didn’t want to move and I didn’t want to leave the house, but initially it was kind of like being very manic.

Anthony Curto: When he died, Sandy, being socially conscious, wanted to make a statement similar to Ralph Nader’s statement, that the Volkswagen that (Harry) was driving in wasn’t properly seat-belted and didn’t have a proper safety mechanism seat-belt. We started to work with safety groups in an attempt to bring action against Volkswagen, and also Supermarkets General who owned the truck that rear-ended him on the Long Island Expressway. He was hit from behind because his car was malfunctioning – nothing to do with the seat belts — and in the process of being hit from behind, the seat went backwards and because there wasn’t a lap belt in this Volkswagen, just an across the chest belt, he ramped up out of the cocoon of his seat, snapped his back and neck, causing a tear in his aorta and he was dead in about 15 seconds, 20 seconds.

The driver of the truck, in an attempt to save him, ran over to the car which was burning and got Harry out. As in an automobile accident case, you have a right to sue the driver and you have a right to sue the owner of the vehicle. The driver was never sued by the estate because of his heroic acts.

Sandy Chapin: I did not want to do it at all. There were a couple of people who had become very involved with our lives largely because of the boards that we were working with, mainly because of the Huntington Arts Council, which was very important to me. One of them was Tony Curto who put together the lawsuit. He came to me, and he was also talking to Harry’s lawyer Monte Morris — there were things happening that I didn’t know about where the car was and who picked it up and what happened to it. Nobody spoke to me that things moved ahead — it was this lawyer talking to this lawyer talking to that lawyer and certain things were being put in place. Then when they talked to me I said no. I did not want to get involved in a lawsuit.

What happened was Ralph Nader — he and Harry were very close — called me at something like 2 o’clock in the morning. It was very, very odd. He said it was very important, he had to talk to me and he said that I must get involved with this lawsuit against Volkswagen because he said he had for years brought up problems with the company, and then he said he would go and have meetings with them, with management and he said they were very cavalier and they would say, ‘Sue us. Go ahead sue.’ And maybe he had or something. But anyway he was telling me this tale of woe and he said this is an opportunity to have the publicity. This is when he was advocating for seat belts. We forget that there were times like that that where there were no seat belts back then. I don’t remember exactly what Volkswagen was doing. Then he said that he wanted to recommend the best product liability lawyer in the country, which he did.

Tony Curto talked to me and he said, ‘I want to put together a team’ and then he talked to me about these three lawyers who would be involved…Then I finally said yes, but all the money would go to the foundation. This was all set up and it was in a contract and I signed the contract. Then the years went by and then on and on and on nothing happened. What eventually happened, as far as I understand, is that Volkswagen was apparently so good and hired such a good law firm that the information that I got was that my lawyers ended up feeling that they were going to lose the case. That was very disappointing. So now it was against Supermarkets General. One of the things that I said was it seemed OK to sue a huge corporation but I said that the driver must not be included. I would not sue an individual. Now I think that that’s the way the suit went forth. I don’t think the driver was mentioned. I never had any impression that he was; it was just against the company.

My instinct was that the car had broken down and that it was human error, whatever the circumstances. I just could not bring the suit against another person.

Josh Chapin (Son): That time was a little weird because my mom was still heartbroken that her partner wasn’t alive anymore. She didn’t want any money. She certainly found a way to do stuff with it but after the settlement and after we were left a tremendous amount of money — and everybody knew it because it was in the newspaper — everybody wanted a piece of it. Everybody. Family members, anybody my dad worked with.

He liked sycophants. He liked people who were going to tell him how amazing he was and he didn’t have any quality control. If anybody took him seriously, he was going to take them seriously. It was nasty. It was like it just had a nasty feeling about it. We’ve all benefited tremendously from the work that was done. But yeah, it was stressful.

***

Ken Kragen (Second manager): I have nothing but great memories of Harry. When I did “We Are The World,” I always attributed much of doing that to Harry and felt at times, ‘Gee I wish Harry was here. He would have really led this activity. He would have really been the one to make things happen.’

On the other hand there was also a general feeling that maybe if he had been there he would have overwhelmed a lot of the artists that were there and maybe people wouldn’t have participated.

Jackson Browne (Musician): I was moved by the way (Ken Kragen) honored him. It made (Harry’s) memory last and helped his ideals to endure.

Ken Kragen: The freakiest thing about “We Are The World” was a Harry Chapin moment in many ways because I had gone to New York to look at the big spread that we were going to get in Life magazine. They did a big cover story and almost like an eight-page spread with photos. We had given them exclusive rights to the photos. Life at that time was still very, very viable. I was being driven away in a car that I owned. I owned an old-fashioned limo from the Thirties, I guess, or early-Forties. I had this car in New York, was being driven to the next appointment and I had this weird feeling literally that Harry Chapin had crawled up inside of me and was orchestrating everything that I was doing. I’m not the most spiritual guy in the world but it was a very, very wild kind of experience to suddenly have that kind of thing happen. I sort of felt like, ‘Oh my gosh, Harry’s running the show here even if he’s not alive.’ [Harry] Belafonte often referred to him as one of our main inspirations in everything we did there.

***

Charles J. Sanders (Friend): I produced the (1987 Carnegie Hall tribute) show and the idea was from a historical perspective to cement Harry’s place in American music history and have him be in the same league as the Woody Guthries, Pete Seegers and have a document that would allow people to look back and see testimony from folks like Bruce Springsteen saying this guy made a difference to me. So that was the driving force behind putting the show together and doing it at Carnegie Hall.

Jason Chapin (Son): At the time, I was living in an apartment above my mother’s office and so I was finding out on a day-to-day basis all the things that were happening leading up to the tribute. I think that was a very difficult time for my mother because Ken Kragen was going to produce it and then he had to back out. Then Charlie Sanders, a good family friend, stepped in and did a wonderful job. But it was just very stressful because there were a lot of contract snags and people pulling out and not knowing who was going to commit and come as far as the performers, and coordinating all the logistics with the Congressional Medal. Then I remember when Bruce Springsteen agreed to come and perform. That just made it a huge event.

Sandy Chapin: I realize that as a family, we have worked so hard to keep up the work that he had started and this involved the Carnegie Hall tribute. That was kind of an interesting experience too because Harry’s friends in Congress had put forth his name for the Medal of Freedom. It was under Reagan, and Reagan turned it down. So then Congress came up with the Congressional Gold Medal — that would have been awarded to a small group of like close family; maybe he would get to invite 10 or 12 people or something to the White House, presented by Reagan and I said, ‘Uh-uh.’ So we arranged through Pat Leahy that the Congressional Gold Medal could leave the White House and we could do this big tribute to Harry at Carnegie Hall because that’s what he was: big crowds, big audiences, the cheap seats and the grassroots. We sent out 25,000 invitations all over the world because he had huge mailing lists. There was a lot of time and effort, and actually expense, on keeping WHY together and Long Island Cares and the Long Island Philharmonic, the things that he had started that were so important to him.

Byron Dorgan (Friend, Former Politician): I offered a bill in the House striking a gold medal for Harry Chapin and got that passed. Then it got passed through the Senate. I did that because I thought the example that the late Harry Chapin had provided was such an extraordinary example that you could be an entertainer, you could have a public life, but you could also use your recognition and so on to make a big difference on something that matters to you. I don’t think anybody had more of an impact on the issue on trying to mobilize the fight against world hunger than Harry Chapin did. And he wasn’t a politician.

Sandy Chapin: Ken Kragen was going to be the producer. (Charlie Sanders) started putting ideas together and talking to people and was working with Ken Kragen. At one point Ken came to New York, invited me out to dinner and said, ‘I have to tell you something; I can no longer be the producer. I have gotten too involved in too many projects that have got me tied up in L.A.’ Charlie was there too — it was Charlie, Ken Kragen and myself. So Charlie, he was left holding the bag and this was not at a point where we could cancel. There were too many things lined up and invitations out and the hall was booked. It was a very complicated thing. I mean it’s just incredible that he could somehow survive through this whole thing because there were people hired, and then people quit, and then there were union problems, and then there were date problems. Basically, what I was doing was I was going to meetings with some of the production people, like the video production people — I would go to meetings in the city maybe about once a week but mostly what I was doing was working a huge invitation list in Harry’s office in Huntington because we wanted it to be representative. We wanted it to be like the Harry Chapin concert, which it certainly was because it was four-and-a-half hours long. It represented a lot of aspects of his life because it represented his work with the arts on Long Island and friends, with “Sesame Street” and kids and all kinds of things as well as some of the people he had worked with in shows like Dolores Hall. It was a really amazing cross section of people and supporters.

I think it was a fantastic evening for everybody but there were so many glitches. The stage manager quit just before the concert and I think there was supposed to be a writer for a script and that fell out. And then Harry Belafonte who was the emcee was back there not getting any instructions from anyone, having to kind of make it up as he went along. Then the video didn’t work. There were a lot of interesting glitches but it was a great tribute.

Charles J. Sanders: It was a wide cross section of performers who talked about Harry’s energy in trying to be a songwriter, and trying to be a performer, and trying to be a social leader, and an altruist, and how he had made an impression on his peers. Graham Nash, Judy Collins, Richie Havens, Pete Seeger, and the Hooters came up from Philadelphia — they were a new band breaking on the scene. They wanted to talk about how they had been inspired and that there would be another generation of songwriters and performers who were influenced by Harry.

The evening was more about peer recognition and establishing that tiny window that we had to work in in terms of before Harry’s memory faded getting people on the record to say this guy lived. I felt that was something I wanted to do. I think it was something Sandy wanted to do and we had an interesting time working together on it. I like to think it was one of the building blocks keeping WhyHunger as a viable organization for all the years that followed.

Byron Dorgan: Carnegie Hall was packed. It was an unbelievable cast of performers all performing obviously for nothing and donating their time. Bruce Springsteen, the Smothers Brothers, Pat Benatar, Graham Nash — the list goes on — Harry Belafonte. It was really extraordinary standing backstage waiting to go on the stage, standing next to Bruce Springsteen and all these people who’ve had been involved in the life of Harry Chapin, and all of them who had been inspired by the energy of Harry Chapin.

Terri Klausner (Performing Artist): It was one of the most fun, incredible evenings of my career. Tom had called me on the phone and said, ‘Hey Terri, we’re going to have the honor of being able to perform at Carnegie Hall to do a tribute to Harry and he’s receiving a Congressional Medal of Honor for all of his work.’ Tom said, ‘We would love for you to be able to participate with us if you’re available.’ I was like, ‘I’m available’ (laughs).

I was seven-and-a-half months pregnant at the time. Tom goes, ‘We have so many stars that we’re doing a lot of the music but would you sing “Tangled Up Puppet?”’ And I was like, ‘Absolutely, I’d be honored and thrilled.’

There we were in the dressing room at one point and Graham Nash came over and just started talking to us and he was as delightful and charming as he could possibly be. I could barely talk. It was just amazing. Then Bruce Springsteen came by. What’s fascinating during that time too was that Bruce came out and mingled a little bit but I never saw him stop writing. He was writing the whole time and I kept thinking to myself, “Gosh, is he writing the song right now that he is going to perform or is he writing what he is going to say?” He had just small pieces of paper and his guitar with him and just was always with a piece of paper on his knee and just writing the whole time.

Most of us, we would spill into the wings if we could. I just hung out in the wings and watched what was going on; watched the performers because I wanted to be there in the audience too. It was just really a thrill. It was beautiful to hear how everyone spoke of Harry. It was just amazing to be there and just be a part of it and see how much his music had influenced all these people. It was spectacular. It was a thrilling, thrilling, beautiful evening and I’m thrilled I just had an opportunity to rub elbows and just be there and also to sing that song to come out on stage.

Jason Chapin: There were some great surprises like when Graham Nash surprised my mother and sang “Sandy,” and then my brother Josh putting the medal on the stool which was representing how my father wasn’t there but it was for him. Carnegie Hall was full and so there were so many fans there that had a chance to be part of that. All the artists from Pat Benatar, Paul Simon and his brothers Tom and Steve and Pete Seeger — it was just a wonderful collection of friends and fellow performers who were there. They all did tributes for other people, but it was just a special plus that it was our father’s tribute and so many people had agreed to be a part of it.

Tom Chapin (Brother): I remember in the concert at Carnegie Hall in ’87 where he posthumously got the gold medal. I called Judy Collins and I said, ‘What song do you want to do?’ She says, ‘Well who’s doing “Cats in the Cradle?”’ I said, ‘Nobody.’ She said, ‘I’ll do that.’ I said, ‘Well Judy it’s great, but it’s from a guy’s point of view.’ ‘No it’s not; it’s from any parent’s, about any kid.’ I said, ‘Bingo.’ So she did it; she’s done it ever since.

Marie “Peachie” Marsden (Friend): Paul Simon, they say he used to go out and do soup kitchens and stuff incognito; he’d dress up different. He didn’t want to be known for doing it, he just did it. Harry Belafonte was the emcee and when he walked in he looked at it, the list, and he said, ‘He’s here, he’s singing! Wow!’ He was impressed with the people that were coming forward to sing Harry’s music. Paul Simon come in late and said, ‘Steve, I’d like to honor your brother. I always loved what he did.’ He says, ‘Well it’s too late for the program.’ He says, ‘I don’t want to be on the program, it doesn’t matter.’

Tom Chapin: These things are more for the living than the dead. I mean it was an amazing night and it was worthwhile. My side of the thing was that Sandy really did all the heavy lifting on it and then suddenly realized she was over her head, and about a week or a week-and-a-half before the event called Steve and me and said help because nobody had talked about the specifics of it, you know. So we kind of jumped in the end, which we were perfectly equipped to do and did that. I mean it was an amazing night. For the people who were involved in it, it was a really emotional, transcendent night.

Springsteen was brilliant; he always is, right, but he was brilliant that night articulating why we were there. But what’s come full circle is the fact that it’s 40 years of great work in the hunger issue. That’s much more important as far as I’m concerned.

In terms of Harry’s legacy, Holy Christ, you know, the great musicians, the Gershwins and [George M.] Cohan and Irving Berlin have won the same award that Harry won and that’s great company, but what Harry’s done is pretty unique, you know. It’s kind of in the world of Roberto Clemente — people who transcend what they do. They use who they are to move it into some other way of helping humanity. I mean that’s pretty spectacular.

Josh Chapin: To me, when I think on that tribute I see my mom being stressed but actually really impressive — and it makes me love her even more — because she really poured her heart and soul into things when she really wanted to go away and not be the keeper of the flame a lot. She loved the man so much and believed in so much of what he was doing, and just missed him.

***

Bill Ayres (Friend, WhyHunger Co-Founder): You talk about some wonderful moments, the wonderful moments for the most part are that over the years people have come into our world with talent, with money, with other resources, with connections and have just been wonderful to [WhyHunger]. There’s no way we would have made it without those connections. Harry had made a lot of those connections. I made some too but he had a lot of those connections and people didn’t give up on us. I mean everybody thought that the organization would just go down the drain after he died but we said no. None of the hunger organizations that we started went down the drain.

There are a number of younger people who grew up because their parents loved Harry. There’s a whole generation of people who never saw him and most have never heard of him. But it’s interesting that there are still a number of younger people who have been turned on by their parents. He created this whole genre of music called story songs, which is pretty interesting.

Don Ruthig (Personal Assistant): There were times when you’d just get so wrought out and frustrated because he couldn’t keep them focused and you’d say, ‘What the hell am I doing this for?’ And then you listen to his music and I think to some extent that’s still the reaction is that, you know what, it was his music more than anything to me. I understand the man and all of his charitable things but where he related to most people was through his lyrics and through his concert work. When I think back on him, that’s what I remember.

Josh Chapin: (The Harry Chapin Foundation) was money that was taken from the settlement and we put aside. So from that three or four times a year we make grants. It’s a small organization comparatively to some of the larger ones, but I mean we usually give away about $75,000 to generally arts and education, community programs that are trying to feed people. It’s usually about self-sufficiency and small organizations that are making big differences in their communities and that kind of carrying the mantle of what my dad believed in.

***

Jen Chapin (Daughter): The weird thing would be in this family if you decided you were going to be a stockbroker or a doctor even. But there was no pressure to do a responsible career. So I would say it was as much my uncles because I didn’t connect directly with my father. What I really see his legacy to me as an activist more than as a musician. I think I got my musical values from the wider family.

I often say if my dad were alive I probably wouldn’t be a musician because he would be so oppressively supportive that I wouldn’t be able to deal with it.

Jono Chapin (Son): It’s going to be different for different people. For some people, it’s all going to be about the music. For other people, it’s going to be about the activism. For others, there’s specifics of poetry or what he meant to this cause or that cause. So inevitably I think that’s the case because I think there were so many facets. The ability to know more about Harry is there and I think in a lot of ways that’s maybe the fun of it is to bring that out. At the same time, I think the lesson is probably that we all have talents; we just have to kind of find how to bring them to the fore and that’s an ongoing process. Some people emerge to be feckless artists and they didn’t pick up a paintbrush until their seventies. So it’s just an ongoing process. Some of us are blessed with having certain magnetism that is there earlier on and can latch on to it and have modes of expression where others that may be different. I think the message is that reach inside and be willing to explore not only what each person has to offer but what you can do together.

Nancy Heller (Friend): Harry would not care one bit about whether they name a road for him, whether he gets in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, whether they make a stamp for him. He could care less about any of that. For him what would be important was to know that people were still caring about his music and his causes and trying to make the world a better place, which sounds kind of hokey but he believed that it takes all of us to make the world a better place. We all have a responsibility to help make it a better place. He was sort of the spokesman for doing that.

Howard Fields (Drummer): We try to tell his story too with the concerts we do. We don’t just play the music; we tell little anecdotes and give a sense of what it was like to play music with him, to record music with him, just to be around him in general so I know what you’re talking about.

That’s what’s paying the bills on those shows. Harry’s fans come and they see his band and his family and we’re doing the songs that they love, so that’s what they are all about.

Big John Wallace (Bassist): His legacy to me comes right down to the fact that everybody can make a difference. I mean one person can make a difference and I think that’s what his life shows. Here’s one guy that decided he wanted to make a difference in the hunger situation. He really did think it was an obscenity that in the richest country on Earth, 20 million people, were going to bed hungry…He knew that one person could make a difference and instead of crying about things and bitching about things and doing nothing, it was get off your ass and get out there and do something. That’s how he lived his whole life. Holy shit!

###

###

Share your feedback with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.