By Lanny Cordola

When U2 made the trek to Berlin in the early 1990s, their mission was to record the follow-up to their great American homage: Rattle & Hum. However, the nexus of chemistry was on wobbly pins. The Berlin Wall had just fallen and exuberance was in the air, but other invisible walls had been erected in the intricate interiors of the band’s delicate ecosystem: Those Nietzschean walls — those walls of flabbergast & frustration — those cagey walls that trick and seduce.

Badly hung over from the dirge of WWI, Berlin in the 1920s was whirling with a new sense of freedom and lunacy; they called it the great experiment. It was a wombat infested, vampiric culture of music, dance, art and modernist Dionysian revelry. There was an explosion of shadowy, illicit pleasure palaces exploring the titillation of sexual deviance — a sextropolis of erotic bombardiers. Hanging in suspense was a decadent dramaturgy in pure Technicolor madness, perversion as catharsis, and dada apostles reviving ancient Greek mystery rites. They threw God out of the house and forged an alliance with the devil — and as most of us know that is filled with dire consequences — so when Berlin finally imploded in the 1930s, his master puppet one crazed Austrian named Adolph Hitler was dutifully waiting in the wings, ready to obliterate this Brechtian 3 Penny Opera into an inferno of jack boots, brown shirts, and homicidal hound dogs.

After the allies toppled Hitler and his minions in 1945, they had a new boogie man to deal with: Joseph Stalin and the catastrophe called Communism. Berlin was now separated by the wall of division and the fatigue of tyranny. What Stalin didn’t know was that Berlin is resilient, patient, and able to wait out its perpetrators. Berlin makes art out of pain and peril; it attracts curio seekers like David Bowie, Brian Eno and Iggy Pop, who in the mid 1970s had a brief encounter when they immersed themselves in the sounds of the divided city. They were experimental Jungian cantors, dark wave deconstructionists, hypodermically injecting the pulse of the demimonde, shedding skin, discovering artifacts, seduced by its intrigue.

In 1989, that wall of division came crumbling down. Now Berlin was in the buzz of reunification, electric boogaloo makers swarming the streets in drunken, euphoric frenzy. This was the Berlin U2 bunkered down in, to reinvent and excavate. You could see the ghost of Dietrich Bonhoeffer dancing a jig and sticking his tongue out at the emasculated Nazi soul suckers, forever chained to their irrelevance. But as the city raged on, the four bloodied mystics of U2 were in the collective midst of a dark night of the soul — the reunited city, the divided band. It was here they would tackle their demons like St. John of the cross. Four Irish pilgrims in dilemma, armed with only themselves and their art seeking to wade through the pygmy propaganda in jagged Elvis Kierkegaardian swagger.

In 1989, that wall of division came crumbling down. Now Berlin was in the buzz of reunification, electric boogaloo makers swarming the streets in drunken, euphoric frenzy. This was the Berlin U2 bunkered down in, to reinvent and excavate. You could see the ghost of Dietrich Bonhoeffer dancing a jig and sticking his tongue out at the emasculated Nazi soul suckers, forever chained to their irrelevance. But as the city raged on, the four bloodied mystics of U2 were in the collective midst of a dark night of the soul — the reunited city, the divided band. It was here they would tackle their demons like St. John of the cross. Four Irish pilgrims in dilemma, armed with only themselves and their art seeking to wade through the pygmy propaganda in jagged Elvis Kierkegaardian swagger.

After much toil and many false starts, they began to go deeper into the tower of song into its mystery and resurrection. Soon, they found the truth of motivation and reformation of mission and what emerged would be a cross between the jazz prayer of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, the dark revelations of Bowie’s Berlin trilogy, and the cabbala of Bob Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks.

The former Nazi hangout now known as Hansa Studios had seen better days since Bowie and Pop recorded there over 10 years before. The equipment had grown weary and the studio was a shambles. It overlooked the spot where the Berlin Wall had once stood the year before. But that did not deter this collection of subterranean Philip K. Dicks, which also included Eno, Daniel Lanois, and Flood who were all on a mission.

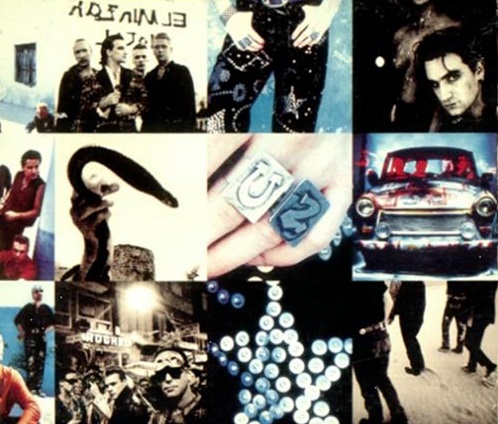

The themes were big: betrayal, doomed romanticism, McLuhanesque artifice, the ambiguity of faith, and a dance with Salome. Of course, there was God, laughing gas, and gridlock (“Zoo Station”). There was Rilke (“Acrobat” and “Trying To Throw Your Arms Around World”), Kafka (“The Fly”), liturgical ache (“Love Is Blindness”); epiphany and satori (“Mysterious Ways”); higher laws and broken temples (“One”). It was a collection of druidic soul hymns that would come to be known as Achtung Baby.

Pulling back the shades is a new DVD release called Achtung Baby: A Classic Album Under Review. This is a critical analysis that features a coterie of pundits and talking heads, including Uncut magazine contributing editor Nigel Williamson, Time Out magazine’s Andrew Mueller, the BBC’s Stuart Bailie, and other journalists and opinion slingers. They give insights and anecdotes on the making of this pivotal record. There are also live and studio performances, some previously unseen photos, and a few odds and sods that illuminate this landmark recording.

Listening to Achtung Baby, one can feel la dolce vita, the divine comedy, the religion, the confusion, the hermetic insight. For by sermon or by sorrow in the muddle is the soundance. This was U2 as Teflon guerillas jagging through the ballyhoo of jihad, a band of Sufi John the revelators, holders of the secret key to melody, lyric, rhythm, and chord.