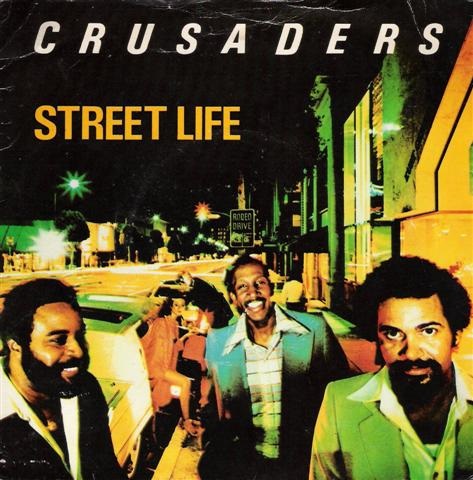

Photos courtesy of Stix Hooper

What makes the late 1970s so unique musically is the fact that multiple genres all managed to secure their own distinct place in time. Sure, you would have standouts like disco and dance-oriented pop filling ears in tandem with harder, more arena-based rock groups. Aggressive and biting punk rock would jaggedly cut out a piece of the proverbial music pie as well — completely uncaring how much of the filling spilled out its sides.

And then there would be the expansive, colorful world of jazz fusion. Having spent years incrementally building commercial success — crisscrossing the globe with rotating lineups – jazz groups and instrumentalists would now make sizable dents on the pop charts. Whether it was “Saturday Night Live” (Sun Ra cough cough), Austin City Limits (hi, Pat Metheny Group!), or “The Midnight Special” (“Today’s Weather Report calls for unexpected groove courtesy of bass player Jaco Pastorius), mass media tuned in and turned on to jazz and its expansiveness. Artists would be signed to larger record labels and suddenly see their fortunes shift from cult to platinum virtually overnight.

One prime example is the Crusaders, a band that established a devoted jazz following over nearly two decades and more than 20 studio albums. In 1979, the group – then a core trio of musicians Wilton Felder (saxophone, bass), Joe Sample (keyboards), and Nesbert “Stix” Hooper (drums) — would release their seminal masterwork, Street Life, an album that propelled the group beyond the jazz aesthetic and landed them into pop music’s Top 20. Bolstered by the album’s brassy title track, Street Life would be certified gold by the RIAA, ensure the group was seen as much as it was heard, and ultimately be cemented as one of “1,001 albums you must hear before you die.”

“When we were the ‘Jazz Crusaders’ as opposed to the Crusaders, we had become very popular on the West Coast. We had roots in Los Angeles, and it was very exciting because our popularity just grew and grew and grew,” Stix Hooper, now 86, told me recently. “People liked our music; they liked the combination of the jazz feel and the spontaneity of what we were doing creatively, but also the tightness of the band. In those days when we were first getting together, it was more or less like one take and that was it. The band had to be tight, you didn’t get the chance to do overdubs. So that was one of the things that made us popular.”

Hooper, who has played with everyone from B.B. King to Larry Carlton (at one time a Crusaders member) to Shuggie Otis, described how the recording process for the six-track Street Life album was equal parts fun and structure.

“We just thought we would go into the studio and have some fun with it. That was the whole idea,” he said. “It was just one of those things where the spontaneity happened and the creativity and all that stuff was going on, but there had to be some structure because of the format and because of the size of the band and all that stuff.”

At more than 11 minutes long, “Street Life” is an opus of an opener, beginning quietly with saxophone riffs, underscoring keyboard chords, cymbal taps, and the rise of strings until we hear the seemingly innocent voice of singer Randy Crawford setting the scene. You may initially wonder who Crawford is but for any fans of Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett, rest assured you’ve heard her voice before – specifically on his song “Hoping Love Will Last,” on his second solo album, 1978’s Please Don’t Touch!

Up until this point, there had not been many vocals on a Crusaders track. One notable example is “Keep That Same Old Feeling” off the group’s dynamic 1976 album Those Southern Knights. Funnily enough though, the song’s primary lyrics are the words in the title.

After 90 seconds, listeners will be able to hear the pulsating heart of “Street Life,” driving by a pumping bass melody and horn punctuations. The imagery could conjure up Los Angeles, New York City, or any city that exudes auras of the unexpected, the ambiguous, and the sensational as Crawford sings the following lyrics:

“I play the street life

Because there’s no place I can go.

Street life, it’s the only life I know.

Street life, and there’s a thousand cards to play

Street life, until you play your life away…”

Randy Crawford declined through a spokesperson to comment for this column. Hooper told me that while Crawford’s vocals would help give the track its power, the original vocalist considered was noted jazz vocalist Nancy Wilson, who due to scheduling conflicts was unable to participate.

“In the studio, (Randy) had the sensitivity enough and ─ as we say in the business – the chops,” Hooper said. “She had to get into the feel of it because it was a different arena for her primarily. Even though in her heart and in her soul musically, I think she felt some of that. But we just had patience because we were all convinced she had the vocal ability to deliver. We felt comfortable that she would be able to deliver and she did. Of course, she was in a much more comfortable zone when she got into the groove of the song.”

While the band reveled in creating a one-of-a-kind multi-minute track, the next obstacle proved to be making their record label, MCA, see the commercial light, according to Hooper.

“The record company thought it wouldn’t get any airplay. It was almost 12 minutes… but it was played all over the world like that,” he told me. “That was something that I can say we can put our feather out there. We let people know that was what we stood for or let people realize that music doesn’t always jump right into the groove. Sometimes music has to speak for itself for what it is. It was great.

“(MCA) accepted what we were doing because that was the nature of what the music was — and music isn’t always a two-minute track to be played on the airwaves,” Hooper adds.

“Street Life” would give the Crusaders their first and only Top 40 US Pop hit, peaking at Number 36.

But the point here is not to emphasize one track but rather the collective whole. Though there aren’t additional lyrics throughout the album to emphasize the point, Street Life could in essence be considered a concept work through its musicality. In addition to the jazz, there’s noticeable soul and funk infused throughout. “My Lady” has terrific bounce while “Rodeo Drive (High Steppin’)” exudes the glitz, glamour, and tempo of the Beverly Hills area itself. “Carnival of the Night” sounds like it comes from the P-Funk canon, complete with Bootsy Collins-esque bass pops. While additional musicians complement the music, the trio of Felder, Sample, and Hooper convey a musical wisdom that gives great heft to the sounds they lay down. Aesthetic convention isn’t the intention here; the goal is originality. If it happens to please the masses, it’s an added bonus.

Per Hooper, in discussing the success of both the song “Street Life” and the album as a whole: “We were all happy about that because we thought that this was proving several points — that music stood for what it was supposed to be and not be programmed… to be put out there according to what the rules are that have to do with airplay and stuff like that. It was not only a fun thing, it was a combination of challenging and being able to deliver something that we felt had substance.

“We did not know what kind of popularity that would be,” he adds. “We knew that it had depth, and we knew that it had the possibility of reaching a larger audience and an audience that would be able to be a combination of appreciating what it was and also to be able to realize that this stood on its own.”

The Crusaders have two additional gold albums within their discography, also worth exploring further in addition to Those Southern Knights — 1974’s Southern Comfort and 1978’s Images. If you can get hold of 1973’s Unsung Heroes, check that out as well. The group also holds the distinction of being an active participant at Zaire 74, the noted three-night-long music festival that hyped up the Muhammad Ali-George Foreman “Rumble in the Jungle” bout in Zaire.

“When [Street Life] was released, we were the headliner primarily,” Hooper says. “It proved another thing, that instrumental music could have popular appeal; that there are people who can appreciate it for what it is and can appreciate the craftsmanship and the musicianship. We realized that. We didn’t go out and do things to appeal to what they called the mass audience or to the industry.”

Like the great jazz fusion groups of the era, the brotherhood behind the Crusaders isn’t for show or performance value. Here you have a group of individuals who thrive off one another because they put the music at the center of their being.

In explaining further, Hooper walked me through his early days as a student at Phillis Wheatley High School in Houston, Texas, where his Crusader bandmates also attended. Citing Wheatley’s creativity and the fact she is widely considered to be the first African American author of a published book of poetry as an example, Hooper describes how any success the Crusaders achieved all harkens back to notions of integrity and craft — in other words, not allowing themselves to be churned out like product but rather taking time to bake and ferment their ideas until they truly satisfied the musical palette.

“We were fortunate to be able to parallel musicianship, craftsmanship, writing, composing, and all of those things, earn a decent living, and find a large enough audience in doing that,” Hooper told me. “We didn’t cop out or prostitute ourselves. We were more enjoying and appreciating being musicians. If we could get a crust of bread by being craftsmen rather than being participants in the industry factor, we were happy with that.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.