By Shawn Perry

Richie Furay may have been a founding member of Buffalo Springfield, but his elevated role in Poco gave him the wings he needed to fly away from the combustible dynamic of Neil Young and Stephen Stills. Together with guitarist Jim Messina, bassist Randy Meisner, multi-instrumentalist Rusty Young, and drummer George Grantham, Furay fused rock and roll with country music, allowing Poco to create a sound and style others like the Flying Burrito Brothers and the Eagles would later incorporate.

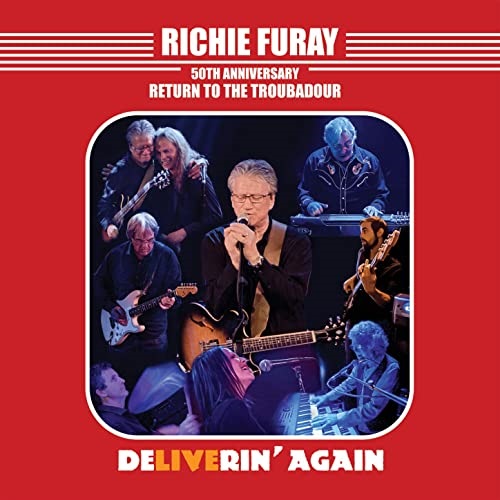

The Troubadour — the infamous night club in Los Angeles where Elton John broke through and John Lennon was asked to leave — is where Poco used to practice and play gigs. Coming back 50 years later for a concert of his own, Furay realized he was going to have to immortalize the opportunity with some sort of homage to Poco. A full reading of DeLIVErin’, the band’s beloved live album, seemed like a good way to go as most of the songs were Furay’s, including the single “C’Mon” and the classic “Kind Woman.”

Three years later, 50th Anniversary Return To The Troubadour brings the night to CD and DVD. Furay, huddled down in Colorado, waiting out the lockdown, gave me the lowdown on the set, the Troubadour, Poco, Buffalo Springfield and the music he’s made and continues to make. We spoke just a few weeks before the untimely passing of Rusty Young, who kept Poco going until 2013.

While Furay hasn’t played with his band — Jesse Furay Lynch (tambourine and vocals), Scott Sellen (guitars, banjo and vocals), Jack Jeckot (keyboards, harmonica, guitar and vocals), Aaron Sellen (bass guitar and vocals), and Alan Lemke (drums) — since the Troubadour gig, that hasn’t stopped him from carrying on. As you’ll learn, the 77-year-old musician has enough on his plate to keep him busy for the foreseeable future.

~

How have you been doing during this whole pandemic lockdown situation?

I think like everybody else, it’s been just one of those things. That’s been frustrating. A year ago, I was going on a cruise with a friend of mine and here we are a year later, going through craziness like we’ve never experienced before. But you know, we’re trying to deal with it the best we can.

You have the 50th Anniversary Return To The Troubadour live set out. You sing about the Troubadour in your song “We Were The Dreamers” and you obviously have a history with the club. Do you recall the first time you played there?

I don’t remember exactly the first time that we played there, but I do remember the circumstances. My band Poco used the Troubadour as a rehearsal hall in the afternoon, and then we would play in the evenings. We weren’t making a lot of money to be sure, but it was right after Poco got started and we needed a place to rehearse. So we rehearsed in the Troubadour during the day and then played there at night.

Clearly, it was a special place for you to do gigs and you’ve captured this beautifully on the live. What prompted you to want to revisit DeLIVErin’?

I was approaching 50 years, you know, of, uh, of just playing music and, and Poco debuted at the Troubadour in November of 68. It was brought to my attention: “Why don’t you think about maybe doing a live recording from the Troubadour? And what do you think about DeLIVErin’.” And it was an interesting concept because other groups were doing live recordings of previous projects, but I don’t think anybody had ever done a live recording of a live recording. So I’m thinking can we really pull this off? And as I got to thinking about it, we were already doing probably three quarters of the songs off of DeLIVErin’at one time or another in my set. And so I thought — you know, we can probably do this. So we started working out the songs and it worked. Doing that 50 year anniversary deal at the Troubadour and then playing DeLIVErin’, which came out 50 years ago — it just made sense. It all worked out pretty good.

When you played through it, did it bring back memories of making the original record at all?

It did, especially when we first started rehearsing it. I would go back and I would think — Wow, what I was doing here when this song was being written. And then I thought about us being one of rock and roll’s first groups to actually play in Carnegie Hall when we recorded that DeLIVErin’ album. Yeah, it definitely brought back some thoughts about days gone by.

You’re joined by Timothy B. Schmidt on a couple of songs here — “Hear That Music” And then at the end of the show for “A Good Feeling To Know.” You guys are pretty tight. Have you guys ever talked about making music together — just going into the studio and doing something?

Well, other than just be supportive of each other’s projects. He’s been on quite a few of my solo projects. He’s even on the album that was recorded in November, last year in Nashville. So Timothy comes out, I haven’t really been asked to come out and do anything on any of his projects. We have a really good friendship and Timothy has always been there and been available.

“Kind Woman”is probably your most well-known song. It was written for your wife, Nancy, who you’ve been with through thick and thin over 50 years. Has the meaning of that song evolved for you in any way over the years since you wrote it?

I never get tired of singing it because I am thankful for the 54. We will have 54 years. It is a blessing because my life went through so many different changes. We almost didn’t make it a couple of times and we decided to work it out. And like I say, it’s 54 years, so it’s always a special time. Like I shared on the rerecording of the DeLIVErin’ project: “There at the Whisky a Go Go, I saw that lady standing right in front of me and there she was.”

On my most recent studio project, I also wrote a song called “Hand in Hand.” And that particular song is a song that looks back where “Kind Woman” was looking forward. I’m always happy to sing it because I’m very happy and blessed with how things have turned out for Nancy and me.

You recorded it with Buffalo Springfield, and then you played it live with Poco several times. The Springfield version to me seems barren from what you were able to do with Poco. It seems like you brought a lot more out of the song. Hearing it on the new record, you seem to be pushing it to its true potential. Do you have a favorite way of doing it?

Yes. I certainly do. The Springfield version, if you count it, there are odd measures in there. And I don’t know why somebody didn’t tell me at the time, “Hey man, why don’t you just put that in straight time?” It became so frustrating to me until I recorded The Heartbeat Of Love record. I was in Nashville and I decided I want to record this and I want to do it all in six, eight, three, four time. And that, that has become probably my favorite version of it. The one that we recorded on The Heartbeat Of Love, which has it in time. For a lot of people, the first time they hear a song, that’s the one that sticks in their mind. So for a lot of people, that original one is the one that they liked the best. I’m not going to complain. I’m going to say, “I hope you enjoy it.”

As part of Buffalo Springfield, Poco, and the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band, you’re often credited as one of the pioneers of country rock. Was “country rock” what you were thinking about back then?

Yep. My influence for country rock came from my dad. He wasn’t a musician, but he did like country music and it would be on the radio quite a bit. So I think I had it ingrained in my heart. And, of course, Buffalo Springfield’s “A Child’s Claim To Fame” has a little country twang to it — even got James Burton playing some dobro on that — and then “Kind Woman.” And then as I moved into Poco, when Jimmy Messina was our bass player at the time, and Jimmy and I, we thought: “Hey, what could we do right now?” And we thought, “Let’s try and do a group that will bridge country music and rock and roll music.” So it was something that definitely we thought about and something that we pursued.

Other people came along — like the Byrds went country when Gram Parsons was part of that. And then, of course, the Eagles and the Flying Burrito Brothers. What is your opinion of some of these groups that followed you?

Well, you know Chris (Hillman) was with the Byrds, and I’m thinking of the Burrito brothers with Gram — they kind of lean more to the country side where Poco lean more to the rock and roll side. But there were certainly groups that were exploring that avenue at the same time that we did. Glenn Frey and J.D. Souther used to come over to my house in Laurel Canyon when I was rehearsing with Poco. So Glenn was hearing some music that he liked and, it was something that was new, it was fresh, and it had an appeal to certainly different people. When we played at the Troubadour, the audiences were fantastic and they came out a lot, so we were onto something. It was just where we were at the time. That was just our music that we were creating, but we did have it in our mind that this is what we want to do. We want to cross country music with rock and roll music. Not that it hadn’t been done from the other side years ago, because some of my favorite music and musicians, early on, came back from like Buddy Holly and Carl Perkins and Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent, and those type of guys that were playing more or less country rock at that time.

And that influence carries over to what’s going on in Nashville today, as far as the country music scene.

I have to say yes, absolutely.

Do you follow any of the newer country rock stars out there these days?

Not so much recently, but as I mentioned before, it was in November 2019, I recorded 14 songs in four days over at Blackbird. We recorded country songs that have really touched my heart along the way. John Barry’s ‘Your Love Amazes Me” — I recorded that and Lee Ann Womack’s “I Hope You Dance.” We also did on this particular project “The River” by Garth Brooks and “Somebody Like You” by Keith Urban. Some of those songs really touched me because I can see that we touched them — whether they know it or not.

You’re in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Buffalo Springfield and you guys got together back a few years ago. Is there a possibility that will ever happen again?

I kind of doubt it. I really do. I mean, the years gone by and age has taken over a little bit. I can tell you though when we did get together, it was almost like we’d been together all those years. We tried to do something back in the 80s and it didn’t work. It was a train wreck. When we got together about 10 years ago, it was like putting a glove on it. It was like we’d been playing together for years and it worked out really well for the amount of shows that we did.

You recorded some of those shows. Is there ever any talk of releasing any of that?

I have no idea. I’m sure that Neil is in charge of all that.

Are you still in touch with Neil Young and Stephen Stills?

I’m in touch with Stephen, but I’m not in touch with Neil. I’ve reached out to Neil on a couple of different occasions over the last couple of years and we haven’t been in touch. With Stephen, I’ll send him a note or something and it may take a couple of weeks, but I always get a response from him. Stephen and I — our relationship goes back a long, long way. It’s not like we’re best friends, but when we do reach out, we respond to each other.

Is the band that played on this upcoming Troubadour release your current band?

Actually, I don’t have a current band anymore. The fact is when that was recorded, that weekend was probably our last show. And, for no reason at all, it was kind of like time to maybe step back. I didn’t know how far we were going to step back with all of this going on now, but it was time to step back. So I do have a group of people that I have played with. My daughter has been playing with me for the last probably 15, 20 years. I decided I wanted to kind of break things down and make things a little more acoustic. I have a guy that plays mandolin, he plays dobro, he plays guitar, he plays fiddle. Having some of those things, that instrumentation, is what I was really looking for when I decided I just couldn’t really afford to take a band on the road much anymore.

So you didn’t have any shows or anything planned before this pandemic?

No, I didn’t.

Just kind of one-offs you think you’ll be doing?

One-offs, yeah. If you’d asked me if I’m going to retire, but I don’t think that’s ever in the cards. I got two projects coming out now. And then in early fall or late summer, I’ve got the Nashville project coming out on BMG. I got a documentary that’s coming out. I’m 77 and I’m just breathing hard (laughs).

Tell me about the documentary.

Well, yeah, it’s (manager) David Stone. I’ll tell you, David has just been tremendous. He’s really been a great fan and support for me, and he just thought, “We should really tell your story because your story is worth it, it’s different. It’s something unique, it’s something different.” And truly it is. I started in 1965 with Springfield and then did Poco and then SHF. And then all of a sudden, I stopped for maybe 10 years. I’m focusing on a different part of my life and, then here I am still playing music. There’s a lot of interesting things to be told and, and David wanted to tell the story.

Is there anything on your musical bucket list that you’re looking to do in the near future or anything that you’d like to do that you haven’t?

My career has been crazy. I played the Hollywood Bowl. I played Carnegie Hall. I played the Bluebird in Nashville (laughs). I can’t think that I’m really missing anything right now. I’m hoping to just slow things down, but you know what, it just doesn’t seem like it’s in the card. As long as I can keep playing and as long as people want to come out and see me, I’m sure there’ll be some opportunities. Hopefully this year, things will open up a little bit and I’ll be able to go out and do some of these songs from not only the DeLIVErin’ project, but also from the Nashville project. We’ll just have to wait and see.