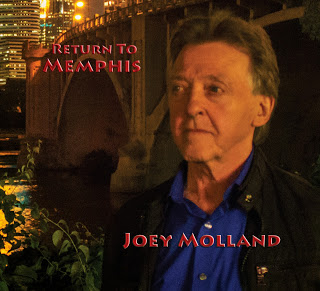

When it comes to what remains of the legendary Badfinger, Joey Molland is the last man standing. As the last surviving member of a band lambasted by tragedy, Molland has weathered many career highs and lows, but continues to record and play live. His fourth solo album, Return To Memphis on UK’s Gonzo Multimedia, is produced by Carl ‘Blue’ Wise and features 10 new Molland compositions recorded at the world famous Royal Studios in Memphis, Tennessee. The album is a slight departure from that Joey Molland/Badfinger sound — something the Liverpudlian guitarist, using different musicians in a new environment, intentionally set out to achieve.

In the following interview, we talk about the process of putting Return To Memphis together. And we step back and touch on Badfinger, Apple Records, the Beatles, the untimely deaths of Pete Ham and Tom Evans (drummer Mike Gibbins passed way in 2005), and, of course, the songs, including “Baby Blue,” which enjoyed a recent resurgence in popularity and airplay thanks to its inclusion on the Breaking Bad series finale. We also talk about a few other musical excursions Molland has been aligned with over the years. All in all, a pleasant chat with a Vintage Rock legend.

~

Let’s talk about your new record, Return To Memphis. I guess this is your first solo album since 2001. And so, I’m assuming since then you’ve stockpiled several songs. How did you end up in the famous Royal Studios in Memphis with Carl Wise and lay these down?

Carl talked to me in 2011 or something, in 2010 — he wanted me to play some guitar for him on a record he was making. He wanted me to play guitar on a couple of songs so I told him I would. About six months or a year later, he called me and said they were doing the sessions and I went down to Memphis and he was doing them at Royal Studios. Of course, I went in the place and it’s just a fantastic place — I don’t know if you’ve ever been there. It’s very old, an old neighborhood cinema. It was converted by … Willie Mitchell and his family, you know, a couple of the Stax and Memphis soul stars, Sam and Dave and stuff, grabbed hammers and nails and built themselves a studio down there because Willie Mitchell went on and founded Hi Records and all those records there. So there I am, playing guitar there and I really just enjoyed it. The guys I played with, Lester Snell and Steve Potts, were just great players. I talked to Carl about it and asked him to get me a budget together to make a record there, and he did, and it was just inside my budget to make a new record so I decided to do it there. And I’m really happy that I did.

It says in the press release I received that you say you were raised on a diet of Memphis music. So I’m wondering — you’re a guy from Liverpool — what did you get out of Memphis growing up?

The very first rock ‘n’ roll record that I really heard was “Blue Suede Shoes.” I was 11 years old and that’s right out of Memphis. That was the record that actually started me playing the guitar. I went right out when I heard that record and got my brother’s guitar out and started to teach myself to play. So it was that big of an influence on me right from the get-go. Of course, all the Elvis stuff, Jerry Lee Lewis, even Little Richard, came out from down around there. It was just a general smokin’ kind of feel of the music from there, and, of course, all the Stax Records just knocked me out. I learned to play, you know, Steve Copper’s licks and I’m still learning them now. The singers, the songwriters, really the whole thing, means a lot to me to go back there. At Royal, they’ve got Al Green masters sitting on the shelf there, Ann Peebles — a bunch of blues artists that I’m not familiar with immediately — a lot of great ones have been there, including B.B. King, and Bobby Blue Bland while I was there. He was actually at the studio planning a new project; I know he’s unfortunately passed away now, but he was planning a new record, standards with orchestras. It was just a great thrill to me, and that’s what I meant by that, I was really raised on that stuff, you know, along with Chuck Berry and a lot of Chicago stuff too.

Right, a combination of rockabilly, R&B, blues. I’m hearing a lot of that on a lot of the songs on Return To Memphis — I’m thinking songs like “Walk Out in the Rain,” “All I Ever Dreamed,” “All I Need is Love,” just to name a few. Was sort of the idea going in, to capture a little of that Memphis flavor?

Yeah, it was. And plus, I didn’t want to make the same record again. I’d been producing my own records, or the past few records anyway, and so it’s been the same for me and I didn’t realize it until I went down to Memphis and played with those guys just how locked into a pattern I was. And so, that was a part of it for me as well. And that’s why I asked Carl to produce it, because I didn’t want to do that. I just wanted to be a singer-songwriter again and play it with a band. So that was really the end of it. I wanted to use all Memphis people just to give me a complete break from what I’ve done in the past, you know. I mean, you always use some of your friends when you record, and they always expect me to want to make a Beatle record or a Badfinger record, and engineers go in that direction. Well, down in Memphis, and particularly at Royal, I put myself in a completely neutral land. They just were going to record me in the normal sense of making a record in Memphis. And I was really happy I did it. And you know what — I’ve been to Liverpool and a few other places since then, and when I’ve played friends of mine the record and told them that I went to Memphis and did it, so many of them have said, “Man, I wish I would have done that,” or “I wish I was doing something like that.” Because we all tend to do the same thing, you know what I mean? And I’m happy to hear you say you like some of it, and that there is a difference in the sound to it.

Yeah, absolutely. And like you’re saying, sometimes you need that change of environment and atmosphere and playing with different players to sort of bring something out new. I definitely think you captured that. That being said, there are a couple of songs there that have that Joey Molland/Badfinger sound. One of my favorites on the album is “Is It Any Wonder,” which just has an incredible melody. Care to comment on that at all?

Well, I wrote all the songs, so they’re all Joey Molland songs, and Carl was responsible for the production of them and made the arrangements and things. All I did was really play the song and then Carl would say to me stuff like, “You know it would be nice to have a bit of slide on this.” And so, when it came to doing the electric guitar bits, I’d work on a bit of slide and he’d get what he wanted in it. So, yeah that did have a bit of a Badfinger-y thing to it, particularly those slide bits. But I don’t think it was — and certainly on my side — it wasn’t a conscious thing. I just play the way I play and sing the way I sing. And that’s all I can say about it, really. If it sounds like Badfinger, it’s because I guess I played a lot of guitar with Badfinger (laughs).

I was going to say, it’s who you are, and no matter how much you try to distance yourself from your past, a lot of times it just comes creeping in whether you like it or not, really.

Yeah, I definitely agree.

Listening to that song, it made me go back and sort of revisit some of your other songs that you did with Badfinger. Two of my favorite songs from the early days that you were involved in with were “Better Days” and “Suitcase.” I’m just wondering now, when you first did come into Badfinger, of course you were a guitar player, but you’re also a songwriter. Was it difficult coming in as a songwriter, knowing that the other guys in the band were also songwriters? Or was that something they were looking for?

I have to believe they were looking for it. I didn’t know a lot about them when I went down to audition. I knew what I’d seen on TV, and a couple of my pals in Liverpool really liked them and they told me about them. As far as I knew, they were a really good vocal band and they were looking to get a bit more rocking. So that was when I went down to see them. I wasn’t looking at them as a songwriter. And myself, although I’d written songs and had a little bit of success with Gary Walker, I didn’t yet think of myself like that. I was just happy that when I got in the band — and I think they were happy to know that I had written songs. Maybe they already knew that — that I had written songs and I had made records before them.

Of course, you did go on to write a lot more songs with Badfinger. By the time you get to the Ass album, you have half the songs there. Were the other guys writing less, or what was going on at that point?

Yeah, I think so. Pete slowed down and Tommy slowed way down. I don’t know why; we were all living together in the same house. I was getting ideas all the time. It must have been my youthful energy levels working or something, because I was getting ideas all over the place for songs. The good lord was willing to send me a melody now and again. It was great. How do you explain these things. Pete wrote all those hits in a row — and then all of a sudden, he stopped doing that. I still don’t know why to this day. But on the Wish You Were Here album and on the first Warners album, Pete’s songs were, I don’t know, not quite so strong, in terms of being up like “Baby Blue.” Even “Day After Day” was a good beat song. And “No Matter What,” of course, was a knock out. It was a surprise to everybody, I think. We just played the songs. We all played our songs and the band [says], “Yeah, let’s play that one.” That’s how we’d make records. I’m happy that you like “Better Days.” I wrote it for Elvis.

Yeah, I’ve always loved that song. There’s a new Badfinger compilation out from Universal called Timeless – The Musical Legacy. And it does have some of those latter-day tracks from Ass and Wish You Were Here. You’ve got the song “Timeless,” which has got to be one of the longest songs you ever did.

Oh yeah. You know, we did six masters of that. Six different takes. We actually recorded the song; we must have done 30 or 40 takes on it over the period we did it. We did it in three different studios with a couple of different producers.

Is that you playing lead?

I’m not sure which take it is, which one you’re getting there. It could be me, but I think the one on the record had Pete on it. It’s his last take. We did a couple of takes where I played. And when I say takes, I mean these are takes that we took all the way to the final overdubs with the harmonies. So there’s a couple of those versions that I played on, but I’m not sure if they used one on this record.

Interesting. peaking of other versions and outtakes and what have you, are there any other unreleased Badfinger tracks that we haven’t heard that may come out some day that you know of?

I’m sure there are. I don’t know where. Again, I’m not privy to a lot of what Geoff Emerick recorded when we were playing in the studio or Chris Thomas. You know, we made songs up in the studio as well and they never saw the light of day, I mean, some of that stuff. So I’ve got a feeling that there are other tracks buried somewhere, but I couldn’t tell you what they were.

There were a few bonus tracks I know on a lot of the remasters that they put out in 2010, which sounded really good. What did you think of those remasters?

I thought they did great on them, yeah. I did, yeah. Apple did really well going back in there and not changing them too much. They didn’t try to make them sound like records that are made today. They just cleaned them up a little, got rid of some noise and maybe added a little reverb in them there, but it didn’t seem like they’d done a whole lot of remastering.

They just sounded really good with the extra tracks. I mean, actually, they remastered the whole Apple Records catalog back then. They sent it all to me — there were a lot of artists on that label I didn’t even know about.

Yeah, that’s right.

Speaking of Apple Records, of course now, back when Badfinger was with Apple, you got to know the Beatles and their inner circle. Of course, we all know Paul McCartney and George Harrison worked on your stuff and you’ve done some of their records. I’ve always been curious — did John Lennon ever have any interest in writing a song for Badfinger, or playing on one of the records, or was that something that he just never became part of or expressed any interest in?

That I know of, John was never really involved in our band. It was the end of the Apple/Badfinger thing that there was a bit of a rumor going around that John would like to produce us. Maybe produce a record for us. I don’t know how serious that is — he certainly never called us up and said, “Hey, I’d like to produce you.” But I believe he liked our band; I think he liked the songs. It was him who sent Harry Nillson “Without You.” He knew it was a Badfinger song, and that lets me know that he actually was listening to our stuff maybe, you know. And, of course, he was nice enough to let us come down or invite us down to come and play some acoustic for him, which was great.

That’s right, you played on the Imagine album — “I Don’t Wanna Be A Soldier Mama, I Don’t Want To Die.”

That’s right, yeah. That’s right.

Were there any others you played on?

We played on “Jealous Guy” that same session, and we only did that one session. Yeah, “Jealous Guy” and I’m not sure if it’s on one of the remixes, but I don’t think it came on the original Imagine album. I don’t think they used our parts. But he gave us credit for playing on his record, and that was good enough for me, really. It was great. I was sad when I found out that they hadn’t used the “Jealous Guy” stuff, but what a great song. It was like we knew it was a classic when we were doing it. Just one of those things.

Of course, you also did play on All Things Must Pass, which I believe will be honored at the Grammys this year. And you appeared at The Concert For Bangladesh, so I guess it would be fair to say that the Beatle Badfinger had the strongest connection with would be George Harrison. Is that about right?

I would think so. Yeah, yeah. He was definitely the closest to the band and he worked with the band a lot more than the other guys; I think he was a bit more involved. He did enjoy the making the records with us. He wasn’t recording with the Beatles anymore, and I know he liked to come and play with us. He’d bring the guitar in and we’d sit around and knock the songs around the way he did with the Beatles. We had the same kind of approach as those guys in the studio, from what I can glean looking at the films of them. I wasn’t privy to go to their sessions or nothing, but it seems like they did the same things with just going in and somebody would just start singing a song and everybody would join in and half an hour later we’d know if we were going somewhere with it, you know. It was great fun.

George was really like — well, he was a couple of different things. He was brilliant in the studio, from all those great Beatles records and all that experience he had making records. He’s a great guitar player and great at thinking up guitar parts. He couldn’t resist picking a guitar up and playing along, do you know what I mean? Finding different things to do, across-the-beat riffs and stuff like that — he was just really good at it. He was really patient with us. He helped us finish our songs, you know, helped us with a lyric here or a lyric there if we were stuck. He was just great to work with. We would have loved to carry on working with him, but, of course, the Bangladesh thing came up and he couldn’t finish our record, he had to go off and do that right away.

But he did play the slide on “Day After Day.”

Yes, he did; he and Pete did. Pete and I were working the side out and George came in and [says], “Do you mind if I play?” “No, go ahead” — I just took my guitar off and gave it to him. I said, “You go ahead. Enjoy.” Next thing you know, he and Pete were working out the slide bits. Took hours and hours to do it right, but it was great. He was great at it; he loved it. He was a perfectionist, had to get it right. He wanted both guitars at the same time — he didn’t want to overdub, you know, do one guitar and then overdub the other. He wanted to do both parts and they were slide parts, and you know how the pitch is on slide guitars. Two guys playing slide. That’s kind of a chance-y thing.

You’re a decent slide player. I’m kind of surprised that wasn’t you or you weren’t the second guy. It was George and Pete that did that.

Yeah, yep. Oh yeah.

So how was it starting that record with George and finishing it up with Todd Rundgren? That must have been kind of a weird dynamic.

Well, it was. It was very, very different. They’re chalk and cheese, George and Todd. But, I don’t know, George told us he was a great fan of Todd’s. It was kind of weird though, because he was so different. Todd was very awkward to work with; he was very rude to us. He had a very high opinion of himself.

So it didn’t go that well?

It actually did go well. We actually made a great record with Todd. And it turned out sounding great. It was our biggest record, Number One, you know, all sorts of stuff. So it was very cool. It was a bit awkward, like I say, we would have preferred to have just finished up the album with George and carried on the way we were going. That’s about all I can tell you about it. Todd came in, did a great job, and like I say, he was rude and insulting. But we made “Baby Blue” with him — we recorded that with him and a lot of other songs besides. We ended up using all the songs that he recorded, so that was all good.

But it wasn’t easy getting there?

No, it certainly wasn’t. And his take on the whole thing was, “You just remember me like that. I wasn’t really like it. I wasn’t really like that.” That’s what he says, but we just really remember him like that.

I know Todd Rundgren rubbed John Lennon the wrong way too.

It was a funny letter, isn’t it? That letter John wrote to Rolling Stone — so funny.

Obviously it’s well documented that the Badfinger story was, despite early hits and the Beatles connection, filled with tragedy due to bad business deals, shyster like Stan Polley, and the subsequent suicides of Pete Ham and Tom Evans. Since then, various songs — and I’m thinking of “Without You,” which was a hit for both Harry Nilsson and Mariah Carey, and, the recent reincarnation of “Baby Blue” thanks to Breaking Bad — they have added silver linings to the story, wouldn’t you agree?

Absolutely, yeah. It is sad that Pete was driven to do what he did and Tommy too, later on, but at the same time, we had a fabulous, fabulous career there for four to five years, very successful and very happy just walking along and enjoying ourselves and living in kind of a bit of a balloon. It was a shock to find out that the world wasn’t a beautiful place and that these guys were crooks. But it was a great time for me; I have a nice amount of good memories and fun times because those tragedies happened after the band had broken up, really. The band was done in I think January of ’75. I’d already left. Peter had left and come back. They’d made a new record, the record was shelved by Warner, the money disappeared again, and I think Peter realized what these people had done and he’d been a fool to trust them. I don’t know what else he realized to make him do what he did. But it’s a damn shame. He had a lot more in him.

It’s really a shame that he wasn’t able to see these songs that he wrote become such big hits. I wanted to ask you about “Baby Blue” being used at the end of the Breaking Bad. Was that something you knew about in advance?

No, I didn’t know anything about it. The Ham estate would have known all about it, because they’re directly involved in licensing of the song. But they never told us about it, me or as far as I knew, nobody else in the band knew or any of the estates knew. So it was a huge surprise. And then, you know what happened, it went to Number One all over the world in the next few days and stayed there for a week or so. I’m waiting to get the royalty statement — we’ll get it next March or June or something — and see exactly what did happen. You know, it was kind of weird, for the next week after that happened, it was like we were Number One again in the charts in real time. Like our band had been relaunched or something. The song was zinging off the hook — every magazine, every TV station, managers were calling, agencies, all sorts of stuff. And then about 10 days after it, the whole thing started to quiet up again. And now it’s dead quiet again; it’s all back to normal. It was like having a hit record without doing any of the work, or even making the record, you know what I mean?

Did you see the episode?

Yes, I did. It surprised the heck out of me. I thought it was a great ending though. You know, I hadn’t been much into the show or anything. I knew it was the last episode, and my son was a big fan. So we recorded it. I’ve got all the shows on my recorder here. So I was amazed. And I was totally amazed on what happened. It was just incredible. Unbelievable.

I’ve always loved that song. I’ve actually got the original 45.

Yeah?

Yeah. Now, at present, are things good in the world of Badfinger as far as everybody being taken care of and all that nasty business stuff? Was that all sorted out?

Yeah, that’s all been done, yeah. It’s all sorted out so everybody’s got what they’ve got coming and I don’t believe that there are any arguments there. Of course, you never know, somebody might think of something, but I’m hoping that it’s all done with. We certainly spent a lot of money in courts and stuff like that. But we ended up getting our money and now everybody gets all their royalties that are all distributed by a central account in London. They’re court-appointed, and if anybody screws up now, they’re going to jail. It’s a legal situation.

And you have a current incarnation of Badfinger going?

Yeah, I have a band that I call Joey Molland’s Badfinger. We do concerts where we just do Badfinger songs. We do all stuff from the albums and all the singles, of course, stuff like “Without You.” And we do them in the Badfinger tradition. We don’t mess around with them or anything. So yeah, I do do that. I also do Joey Molland solo shows, and I’ll be going out with a band to promote my new record.

So you’re going to take a different band out and go out and play the record?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. That’s obviously what I’ve dreamed to do. I’m trying to set up a small kind of theater tour to do that in, if it can lend it self to that, kind of like your Sellersville Theater down in Pennsylvania, that kind of place. I’d like to play those, about three or 400-person theaters. They’re kind of intimate, but at the same time, because they’re a theater setting, you can do a kind of show for them, you know what I mean? I’m looking forward to it, really I’m looking forward to it. I just hope that people get into the songs and enjoy the songs and want to go and hear them live.

And will you also be playing some Badfinger dates this year?

Yeah, I’ll do a few of those. I might be doing, I believe, a tour actually with Todd Rungren, which is kind of a Beatle-y kind of tribute tour or something. And I believe that’s being put together now and I’ve been offered a spot on that tour. And there might be a Hippiefest tour going on, where I go out and do the Badfinger hits.

Cool, cool. Yeah, actually the Hippiefest came through here a year or two ago, but you weren’t on that bill, I don’t think. I think it was like Mark Farner from Grand Funk and some other people. But yeah, that’d be great. That would be great to come out and see. You know, I just have a couple of last questions for you and these are actually about activities you’ve been involved with outside of Badfinger. First, I read that back in 2006 you had a reunion with Gary Walker, who you backed in the Rain, and I read that you two were writing songs and talking about recording. Did anything come of that?

Well we did, and we were planning on stuff but nothing ever came of it, no. We had all the original guys — well, no, Charlie from the Rain, Paul Crane, the singer, had died, passed away several years ago. But yeah, we were talking about going out and maybe doing a few gigs and stuff. But I couldn’t do anything over here, and the people that Gary was involved with, the management company over there, never got their end together so nothing ever came of it, no.

Another project that you were involved with — and I actually reviewed a reissue of this album, probably in the last year or two — was the Natural Gas album, which I really like. What are your thoughts on that record?

We had a tremendous amount of fun doing it. It was a really good rock band. I thought the record was a bit dull, the production of it. But other than that, I really enjoyed it and I thought the songs were good. Particularly, I thought Mark Clarke was like really strong, and what a great singer. Yeah, yeah. It was a lot, a lot of fun doing it. Really tremendous. And I’ve seen Jerry, when we go back to England. I haven’t seen Mark in a few years though other than bumping to him in an airport here and there. But I go and see Jerry. It’s nice to go down there and have a pint and just talk about old times. He’s just written his book, hasn’t he, “The Best Seat in the House.”

Jerry Shirley did?

Yeah, yeah. Great book too. And also, he’s just remastered, maybe remixed, a live Humble Pie album. I believe that’s fantastic. I haven’t heard it yet, but I’ve heard it’s a great job.

It’s actually a four-CD box set, four different shows from the Fillmore run. I reviewed it and it’s incredible.

Yeah, yeah.

I know that with Natural Gas, you did play a few live dates. Was there ever any chance, any talk, of it going any further, or was that pretty much it?

No, we did the record, we went and did the Phantom tour. We’d gotten into a bit of cocaine really, and that’s what fractured the whole band, really. And the guys, we were all living in Los Angeles, and then all of a sudden, the other three guys wanted to go live in New York and wanted to do the record in New York. And the management, the people behind the band, wanted us to stay in LA and do it there. I was desperately trying to get them to stay in LA, do the record, then they could move to New York, you know. But they wanted to go do it in New York and that was the end of the band. It’s a shame because we really enjoyed it. You know, we rehearsed in LA for about three or four months straight, and just the stage show was tight, the band was on, you know. Just super on. That’s really what we wanted to do, was get out on the road and play, but for one reason or another, the cocaine not being the least of it, it wasn’t to be. The band broke up. So there it was.

Well it’s a good record, I enjoy it. And I’m enjoying Return To Memphis. Hopefully you’ll come out to California and play a few dates. I’d love to come out and see you.

I hope so. I love to get out to California. You know, Badfinger wasn’t necessarily the most popular band in California, but we do get a date out there once in a while, so hopefully I’ll be out there and play. I’d love to come back out.