By Shawn Perry

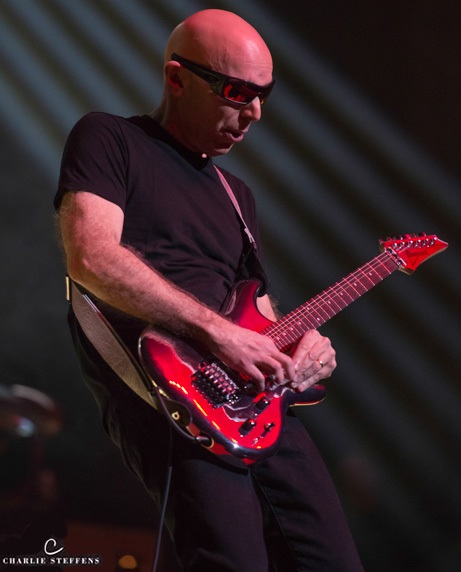

When the pandemic hit the world in 2020, Joe Satriani was preparing to release his 18th album, Shapeshifting. Many acts put the brakes on whatever they were doing and went into lockdown; Satriani pushed forward and released the album, though the idea of touring behind it was put on hold. So the guitarist started to write a new record. Given the situation, he decided to give it a little more time and space. He experimented with new sounds and concepts, and encouraged everyone involved to do the same. The result, The Elephants Of Mars, is a magnificent piece of work, arguably one of Satriani’s strongest efforts since his 1987 breakout hit, Surfing With The Aliens.

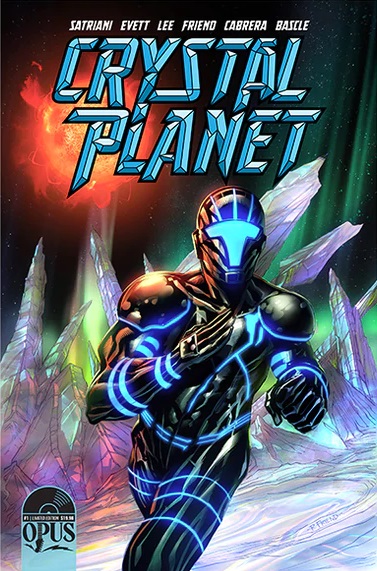

Satriani took full advantage of his time away from the road to not only create music, but to explore other artistic avenues as well. He and his creative partner Ned Everett issued a comic book series called Crystal Planet. The guitarist also immersed himself in painting, debuting his artwork at two Wentworth Gallery locations in January 2022. Ever the Renaissance man, the intersection of art, music and storytelling are vital to Satriani, who’s never shied away from pushing the boundaries of his abilities. Hopefully, when he finally returns to the concert stage for a U.S tour this coming fall, that creative bug will still be buzzing.

In the following interview, an hour-long chat in its entirety, we touch on it all and then some. Unfortunately, this was before Satriani revealed to another interviewer that he and Alex Van Halen were in talks about playing an Eddie Van Halen tribute tour. Actually, it was all supposed to be hush-hush until former Metallica bassist Jason Newsted, who was initially involved, spilled the beans to a reporter. Maybe I should have asked the guitarist more questions about Wolfgang Van Halen. How he came up in the conversation is something you’ll have to find on your own.

~

Let’s get into this new album of yours, The Elephants Of Mars. You’ve been getting a lot of great press and feedback from fans. I gave it a five-star review.

Wonderful. Thanks.

Given the fact that you began the work on this record right around the time the world came to a screeching halt, it seems like you might have had a little more time and space to create something extra special. Is that how it felt going into it?

We had finished the previous album, Shapeshifting, right at the beginning of the year (2020). I think the mastering was on January 1st or 2nd. ZZ (Satriani’s son) and I did the video for the song “Nineteen Eighty” within the first week or second week of January and everything was still going OK. I was down at the NAMM show in Anaheim. I played two shows with Steve Vai. By the time we got home, the lockdown started here in San Francisco. Our biggest responsibility was at that point was really to figure out — number one, should we tour? And number two, should we release the album? I was adamant that we should release the album because people were expecting it. And if anything, if this thing was going to drag on for a few months, we’re going to need some music.

So I thought this is going to be really bad for business, for our business, for my business. But it was important to just move forward with the musical message. So we had to cancel Europe. That was the first of three times. And we released the album in April, as we did this month. And, then we waited.

I initially thinking, there’d be maybe a six-month delay and we’d start the U.S. tour in late September of 2020. And for that, I convinced the guys, we should do two supplemental albums. That’s what I call them. And I said, “How about this? We do an instrumental album. We stretch out, we let everyone solo like crazy. And we do a vocal album and we let Rai sing and show us his really great vocal chops.”

I’m talking about Rai Thistlethwayte, my new keyboard player and rhythm guitar player who comes from Australia and is pretty well known down there for being in a band called Thirsty Merc. They’ve had hit singles, placed their songs on TV shows, and received gold and platinum records down there. He’s a tremendous musician. I just thought, “Well, that’ll be a fun to do.”

But within a few months, I realized what was really happening, which is that this was a global pandemic that was going to stretch on for a long time. It was pretty frightening because we make our living on tour. We spend all the money making the albums as the labor of love, but we actually make a living — crew, band, and even myself to some degree — just playing shows. I thought, OK, this is different. I’m going to have to do a little workaround, plan B or plan C, I guess. Once that really sunk in, I thought, OK, we’re not going to do two albums. I needed to stop and think about what I need to do next.

One of the things that was happening at the same time was that my very long contract with Sony was coming up and that contract started in 1989. It was for a really generous amount of albums and it had a generous amount of options. So Sony was able to, every two years, pick up an option to ask me for another album. The vibes were always good. I loved working with the team there. They always had great employees that always helped me make these albums. And they kept the catalog vital all these decades. But what happened was I realized that there was no one left at Sony that I knew (laughs). I had kind outlived almost everybody there. I think the only person that was still there was Scott Carter, but he didn’t even work anywhere near the department that I was sitting in at the moment, which was Sony Legacy.

I thought maybe this is the time to just stop thinking about making new albums with Sony and start to find a new partner.” And I turned to my friend, Max Vaccaro in Hamburg, Germany, who I met over 10 years ago when working with earMUSIC. He picked up the worldwide rights to Chickenfoot albums outside the U.S. Max is a great guy and great music lover, and we really are like brothers when it comes to the kind of rock guitar we enjoy and, and the other musicians we really like.

So we started talking about maybe starting a relationship. During that period — when we realized we weren’t going to tour and we were just hoping that maybe in 2021, it would happen — I formulated my future, which was, I’m gonna sign with Max and earMUSIC. I’ll continue my projects with Sony, but it won’t be for new albums. We’re doing a remix of Surfing With The Alien right now. There are things that we’ll continue to do. But the main thing was, I said, “OK, this is a moment where I’ve got to do something outrageous. I’ve got to challenge myself in a way that I haven’t before.” I was sort of kicked off the grind there of album, tour, album, tour, album, tour that’d been going on since 88. Then all of a sudden, I had no excuse (laughs).

That’s what it comes down to — it was like one day, one week, one month, you know, you’re thinking, “Well, this is going to change. We’ll get back to normal.” After a year, you go, “Oh my God, this is really devastating for the world, for fellow human beings. I’m not a doctor, I’m not a scientist. What am I going to do?” I thought, OK, I’m a musician. I’m supposed to make music for people. So if you’re ever going to dig deep and make the best record of your career, now’s the time.

I set some lofty goals. I said, “I’m going to write better. I’m going to arrange better. Look for better guitar sounds. I’m going to put a team together and I’m going to let them know this is what we’re going to do. We’re not going to rush. We don’t really have a schedule. And I know we’re all by ourselves. So let’s do what we never get to do when we’re rushed into a studio for 10 days.” We embarked on that and it took awhile, but it was our choice to take our time.

You have some incredible players on board. You have Kenny Aronoff on drums, Brian Beller on bass. Rai, who you mentioned earlier on keyboards, and your producer, Eric Caudieux, who also plays keyboards. Based on some of the videos and discussions I saw, it seems like it was a very collaborative effort. Obviously, you’re the main architect, but with the pandemic in play, I’m wondering: Did you work remotely? Were you in the studio together? What’s the process that took place?

The process was that I would write and I would demo at my home studio. The demos would really be the beginnings of keeper tracks. When you are working with Pro Tools digitally, you are always kind of making the album, even from the start because everything is saveable, everything is editable. A million times non-destructive editing is probably the biggest plus for recording digitally, no razor blades (laughs), no missing pieces of tape on the floor (laughs). That’s how we basically started.

I would program drums or drum loops, I would do keyboard parts, some of which we would keep, if they were automated, then they would be really good in time and all that kind of stuff. But I wouldn’t do any solos or anything like that. I’m not that kind of a player on the keyboards. Same thing with the bass — I’d lay down bass, but it would be a suggestion to Brian like, “This is where I’m going, just do it in a real bass player way” (laughs). Eric, you mentioned, plays keyboards as well. He’s not a crazy soloist like Rai, but he’s a fantastic musician. He’s a really great guitar player. I was shocked to learn about that when we first worked together in 96 and it turned out that he was just a crazy left-handed, French fusion guitar player (laughs). I think that’s why we got along, because we would sit around and talk about John McLaughlin for hours and hours while we were working on different projects.

His sense of harmony and composition is really fantastic. I mean, he’s just really a genius when it comes to that. And, he’s just downright as crazy as me. We’ll try anything; we’ll chase a bad idea for months and then finally give it up (laughs). But sometimes, he does things that are so crazy that I’m just so overjoyed to hear it. A perfect example is I sent him the song “The Elephants of Mars” and it had this weird elephant noise kind of thing. It was kind of like a throwback Nine Inch Nails kind of thing with four on the floor, lots of electronic texture from the band, and it had this very clean blues guitar solo in the middle when it modulated.

Once we started working on it, he took that middle section and turned it into a breakdown section and re-harmonized all chords words underneath it. He moved some of my notes around, but kept the basic performance of the blue solo and created this section that we referred to as the “beautiful female elephant section” (laughs), where the female elephants of Mars introduce you to the wondrous and beautiful side of their existence on the planet. For most of that song, it’s always the male elephants charging along with the revolutionaries to take back control of the planet.

This is one of those things where I’m not expecting it. And he sends me a little note saying, “Oh, I sent you something. You might hate it, but you might like it.” And, of course, I loved it. Once I got that, I thought, I know what the rest of the song is going to be. So I could write the rest of it based on that little moment of brilliant collaboration. I think he helped write three pieces of music out of the 14. Then everybody just would add so much stuff. And because we had the time to sort of audition everybody’s reaction to everybody’s weird ideas, we were kind of spoiled for choice because we had five different ways of doing a song from Kenny. He would just say, “Well, I can do it like this,” but it would be complete. Brian would give us a fretted version, a fretless version, a distorted version, a clean version. I think Rai was the only one that because he was in Tasmania traveling on tour with Thirsty Merc, he was always trying to catch up to the rest of us, who were basically still home bound in California.

So that means there’ll be a lot of alternate tracks and remixes on the 10th anniversary box set, right? (laughs)

Oh my God (laughs). Well, I know one thing, everyone’s excited about that for mixes and we’ve been through this before. I have quad and 5.1, right? And 7.1 (laughs). Every time they come up with a new one, I’m like, “Oh my God, this sounds like it’s going to be expensive.” And the artist always pays the bill for these things. The key is to make sure that it’s non-cross collateralized against your account, otherwise it’s just servitude (laughs).

Given the fact that you began the work on this record right around the time the world came to a screeching halt, it seems like you might have had a little more time and space to create something extra special. Is that how it felt going into it? The first thing I picked up immediately after tracking through the album is this wide range of styles and influences. I mean, you’ve got these Middle Eastern flavorings on “Sahara” and “Doors Of Perception,” the funkiness of “Pumping,” and then these epic orchestrations on “Dance Of The Spores,” “Through A Mother’s Day Darkly,” and “Desolation.” I can imagine you just must listen to all kinds of different types of music for inspiration.

I do. I have just a crazy way of listening to music. There’s no way to explain it. Like some days, I’ll put on two songs by Jimmy Vaughn and I will play to them for for hours (laughs). It makes absolutely no sense other than I’m fascinated by his economy and the strength of his phrasing. And every time I try to play along, I expose myself for not being that style. When I play blues, I play more of a Hendrix style blues because that’s who really introduced me to electric guitar blues. After hearing “Red House,” I started to look back at everything that would have influenced Jimi Hendrix. And that’s how I learned about the blues. Somebody like Jimmy Vaughn has lived it his whole life. So he has a discipline behind that relaxed style that is really devastating. You only know it if you pick up your guitar and try to play along. You realize you’re in the way all the time because he’s already played all the perfect notes. You try to add something and it’s like, “Nah, doesn’t work.”

Other times, I’ll be in my art studio and I’ll be painting for eight hours a day and I’ll just listen to nothing but Black Sabbath or Mozart. I’ll have a day where I’ll just listen to Eric Caudieux. I get in one of those French moods and that’s all I listen to. I really do tend to go all in, in styles that are all over the map as opposed to having a playlist that covers all the styles. I’ll just dive in and stay there sometimes for days. Like I’ll just listen to nothing but Black Sabbath for four days and I’ll get eight canvases done. The paintings aren’t connected to anything that they’re playing or singing about, but it’s just sounds good to me maybe because I was a young teenager when they came out and it’s just part of the soundtrack I use.

One of the things I’ve always loved about your music is just this minute attention to detail — the layering and the texturing of the arrangements. I think this type of approach is what separates players like you and Jeff Beck, as an example, away from a lot of these other guitar players who get caught up in technique and speed and histrionics and all that stuff. I think this is really where your compositional skills align with your skills as a player. This was obvious when you put out Surfing With The Alien. How important is composition when you’re putting these records together?

It’s the most important of thing. I don’t put one foot in front of the other until I think I have the beginnings of a great composition. I’m saying within my little world, I write a lot of songs all the time. I can tell if a song’s got the potential to really be a good example of what I do best as opposed to an OK example. So that’s what I’m really focusing on. I’m trying to express myself on a specific feeling about a specific person, event, something I experienced, something I’m imagining, something I’m hoping for, something I regret. I just distill it and distill it and concentrate it and crystallize it until it really suggests to me what it should sound like if I want to get that feeling on tape.

Sometimes it’s a very deep journey into a place that I don’t want to go. I don’t want to feel sad, so I don’t want to think about it, but I have to force myself there to uncover feelings that I’m trying to bury. Sometimes it’s silly and I’m the thinking, that’s too silly. You should never let people know how silly you are, but then I go, “No, don’t discriminate. It’s OK to write a song about driving in your car at the beginning of summer.” So that’s made me feel OK to write a song like “Summer Song.” I said, “Yeah, this is not a heavy song. It’s not deep. It’s got no extra hidden meanings. It’s just about feeling good. School’s over, you’re in a convertible, it’s summertime and you’re driving.” You know, make that sound, whatever that sound is, experience that sound and explore it. So, then I guess this is the important part. I start to work on the song. I’ve already got the title, the story, maybe I’ve drawn a picture. I just use those elements to keep me focused so that I don’t add in all that other stuff that I can play. I only use musical tools that support this title and this inspiration. Then if the song reaches out to me and says, “Boy, it would be great if you could play like that.” If I can’t play like that, then I’ll spend days or weeks teaching myself how to play it so that I can make the song happen. The meaning of the song drives my technique. I’m not creating a song to show off my technique. It’s really quite the opposite.

I think the perfect example would be many years ago, I wrote a song called “The Mystical Potato Head Groove Thing” for the Flying in a Blue Dream album. We had already started the production of the album. When I came up with this song, I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if instead of a chorus where you modulate and you play some high notes and some harmony guitars come in — what if it was just this little barrage of aria notes.” I thought that would be really great because that’s what I want to hear but I don’t know how to play it. So I started to play it and I thought, “Well, that would be great. Who do I know that can do this? (Laughs) Because it’s not me unfortunately.” So I thought, “I bet I can do this.” So I called up (producer) John Cuniberti and I said, “OK, we’re going to have to take a three-week break from the studio because I’ve written this really cool song and I can’t play it. I’m giving myself three weeks. So I’ll see you in three weeks.” So eight hours a day, that’s all I did was play these strange arias to see if I could pull it off. And then that one day when we started up the layering of the track was quite easy, but it was like, “Can you do these arpeggios and make it sound convincing?”

You know the only danger there is — and I brought this up to Kenny on the last record — I said, “Be careful what you play on an album because if people like it, you’re going to have to play it for the rest of your career. And it better be something you can play otherwise you’ve just embarrassed yourself every time you hit this stage.” (Laughs) That got me, those arpeggios. Every time I think I want to play that live, I have to spend at least two months starting from scratch and just teach myself how to play it. It’s at the edge of my technique horizon (laughs).

With all that being said and how you put songs together, the title “The Elephants of Mars” got me to do some digging around. I found this image of an ancient lava flow on Mars that someone said looks like an elephant. You’ve probably seen it, the Mars elephant. And then I read about pareidolia, the science of how and why the human brain sees objects like elephants in random shapes like ancient lava flows. I was trying to see if there’s any connection to the song, but then I saw that video you and your son ZZ made and I said, “No, I’m completely off.”

(Laughs) That’s funny.

You do have these cinematic qualities in your music where certain visuals and shapes must be popping into your head when you’re writing and playing.

Yeah, it is important. As I mentioned many times in the social media interviews about that song, the title track, I’m listening to something that I played and it got me thinking: How am I going to be motivated to finish this song? And I realized I needed a backstory. And so I concocted this story about the scientists terraforming Mars, and by accident, they create a whole race of gigantic sentient elephants. And they can communicate telepathically to the colonists that are working on the newly terraform Mars. They can play crazy rock sounding music with their trunks and they get together with the guitar playing head of the revolutionary group to take back control of the planet from evil corporations — you know, a typical comic book kind of story.

That got me really excited because I thought that’s funny, it’s crazy science fiction, but it’s also kind of funny. So when I told the story to everybody else, everybody got in the right mood. Kenny’s drums are just really a celebration of fun, the way he plays, right from the beginning. I think it gave Brian the artistic license to just be really rude, to lay down a really rude bass part. All the way to the end where I think Rai was the last person to add the keyboards. He added a kind of a Jon Lord, a Deep Purple kind of distorted organ part. We had been talking years ago about how we love the vintage Deep Purple and how we love Jon Lord. When you tell that story to everybody, everyone gets in the mood and they go, “Now I’ve got this artistic license to really be crazy, to be a irreverent, to try some different things.”

The opposite would be you walk into a studio for a three-hour session, somebody gives you a chart and you go, “OK, let’s go.” And you play conservatively so you don’t mess anybody else up because you just want to get the track done.

We were all recording remotely and on our own schedules, so everybody had the chance to really stretch out and do what they always wanted to do on a song like such and such, which is kind of like the mood I was trying to foster in everybody. So the album would be unique in that sense. It would just have song after song of brilliant performances that each musician felt they never got a chance to do on other albums.

You have three music videos I’ve seen so far from the album. Your son ZZ, who I mentioned earlier, is in the director’s seat on these. I would imagine this is something that you and him probably work on closely.

We started doing stuff together with video when he was still in grammar school. He was making skateboard videos and we were still taking him on tour a lot, up until high school. I guess from the age of four until when high school started, he was out on tour with us just about every summer and sometimes in the other months of the year as well. We pressed him into service to make those irreverent podcast videos for us. He slowly would teach me how to do it because he was getting bored following a bunch of old guys around with his camera (laughs). Eventually, he gets a degree in filmmaking at Occidental down in Southern California and studio art as well.

We did a documentary called Beyond The Supernova. I think it’s finally available on Amazon Prime and iTunes as well. We started doing lots of music videos for the albums. At the beginning of 2020, we did the “Nineteen Eighty” video. I think this is a perfect way to answer your question about how we work. I send him the track and I go, “What do you think?” And he says, “I got this idea.” And I basically say, “Just tell me what you want me to do. What color guitar do you want? What should I wear?” (Laughs) His only comeback was, “Where can I get a lot of Marshall stacks?” So luckily, Hugo Martin at Marshall was so kind in finding me a source that we could have all those stacks of Marshalls in that one big white room, because I had to do all the performing there in the room. But that was all ZZ’s vision. I’m so used to working with him that I basically just say, “What do you want me to do?” And he just tells me and I just do it.

Fast forward to a few weeks ago, we’re all in this green screen studio. Basically he’s jumping up and down and telling us what to do, filming us with this really odd 360 camera. What he wound up doing for the song is so intensely layered in terms of environment that none of us could have expected that that’s what we were going to get. We were just a bunch of guys hanging out in a green screen room, having no idea what it was going to look like at all. As he was explaining in the online event the other day, he said, “It just took a lot of 10-hour days of building digital environments.” So he would place us in there. His idea about the video game I thought was really great. I think sometimes with an instrumental song, if you try to tell the story, you lose an opportunity to add a component to the music. So rather than me saying, “No, you have to think of this science fiction story that I’ve created,” which, of course, would be way too expensive to try to film anyway, you think, “OK, what if nobody heard this story of Joe’s about terraforming Mars? What could the song be about? And how could it be fun that would give the song another way of looking at it, another life.”

So his idea to make it like a video game to save the elephants and to bring in the actors I just thought was really great. It was right in step with what I was using to get everybody in the mood for recording. As I said earlier, I wanted to give everyone the feeling that they had artistic license to kind of go crazy in any direction that they felt, not to worry about clock on the wall or a date on the calendar. In this particular case, the musicians then that showed up, we all could just goof around because we didn’t have to sell some sort of serious science fiction story with the video.

I thought the funniest thing was that he had to record Rai remotely because he was in Australia at the time. And so he had a whole role for Rai scoped out where he was going to be the professor, like in an old-school video game where he’s the character that tells you to remember to push this button or get extra points or get extra straight by doing this. I just thought that was really great. It’s a great way to introduce Rai to my fans as a new band member, too.

You talked about the story behind “The Elephants of Mars,” and I know you’ve worked on a comic book series called Crystal Planet with Ned Evett, who appears on the record. Are there any plans to maybe The Elephants Of Mars into a comic book? Are we going to see more comic books from you?

Ned and I started this company called Satchtoons maybe eight years ago, and the idea was to create stories that we could then get made into either novels, short stories, published in comic book form. Certainly, we wanted to do animated features as well as eventually a real movie, if the story really warranted it. Like Crystal Planet could be like a real action film, an epic film. He does a spoken word on the album for a song called, “Through a Mother’s Day Darkly” and he’s really talented that way. I mean, he’s got a million voices that he can do and it’s really amazing. And he’s a really prolific writer.

When I had this idea for the story of ‘The Elephants of Mars,” I basically told it to him over the phone, like I explained it to you. Like many conversations that we’ve had over the years, he says, “I’ll get back to you in 24 hours.” And, of course, he does and he’s written a more professional version of the story with the prequel and the sequel and the characters. It’s really remarkable, his talent to take a little diamond in the rough of a story and just blow it up into something that you could spend years enjoying — all the episodes and the novels and the sequels (laughs).

I just got a box of issue three of Crystal Planet, which is great. We’re moving forward. We were hampered by supply chain issues. I think the Joe Satriani action figure is still sitting on a barge outside of LA (laughs). Just sitting there in the Pacific Ocean with no one to unload them. I think there’s millions of them. It’s not the end of the world that you can’t have a Joe action figure, but we’ve been hit with that. The comic books are completed in London with our team Llexi over at Incendium and OPUS in association with Heavy Metal magazine. Our international partners are hurting, too. Just getting things moved around the world is so hard still, but we are on track to deliver the graphic novel for the story Crystal Planet. And we do hope that we can publish a book of about 25 stories that we have so far. That’s what I’m moving towards; one of those Post-it notes on my desk of things to do is to get those stories in a book form so it’s a lot easier for us to share with people like yourself or people in the industry that are looking for properties to turn into animated or action films.

Aside from conceptualizing comic books and putting the record together, you, as you mentioned earlier, are a painter and I know you did a couple of showings in Florida earlier in the year. You’re a real Renaissance man. How long have you been painting?

Seriously, I suppose about eight years. I grew up in a house where my oldest sisters were professional artists and they got degrees in fine art. So there was always art in the house and art materials. I wound up marrying an artist who has her degree in graphic arts and our son wound up getting a degree, as I mentioned before, in film and studio art. So I’ve always been around really talented artists that have very different views about art and different kinds of talents. But again, art materials everywhere and I kept sketching ever since I was a young kid. The sketches wound up on guitar picks, guitar straps, tour merchandise, CD packages.

At one point, I turned my wife and I said, “After I put out this digital art book for the fans, I want to get my fingers dirty with paint and I just don’t know really how to go about it. So teach me about canvas and brushes, which brush do you use for this and what kind of paint to use for that.” So she started guiding me into how to use the materials. I made about a hundred pieces, mainly portraits of really strange looking creatures, which was my forte (laughs). That was really an extension of my drawing. By accident, I get called by the guys in LA. They have an art collective art house called scene SceneFour. Cory and Ravi are the two guys who run that and they wanted to do some time-lapse photography of me playing my guitar in the dark where I wore these LED light laced gloves. So the photograph wind up being these beautiful multicolor trails of my finger and hands movement across the guitar. Then Ravi manipulates these things in the computer and they print them on canvases and they make these really stunning pieces of artwork.

During the break that one day when we were doing the photography, I happened to show Cory some of my artwork and he was really enthused about it. And then we started a series where it was mixed media where they’d take some of the prints and combine it with some of the digital art that I was doing before printing. Then they’d send the canvases to me and I would paint on top of them. They turned out really well. And so then they introduce me to Christian O’Mahoney who owns the 10 or 11 Wentworth galleries up and down the east coast, from Jersey down to Miami.

He commissioned me for 11 guitars and another 150 paintings. So I have been really busy doing a lot of paintings. And I love it. I mean, I really, really love it. It’s just been so much fun. I’ve learned so much about what I like about different painters and what I’d like to achieve.

Doing the art openings reminded me of how much I miss going on tour because they were actually the first public things I did since lockdown. That was unusual and I didn’t really know what it was going to be like. The first one we did was at the Hard Rock casino. They have a gallery there. I remember walking into it and I thought, “Wow, my paintings are on the wall of a gallery.” This is like hearing your music on the radio for the first time (laughs). It’s so bizarre, this can’t be happening, that painting of that alien used to just be in my basement. Now people are staring at it and it’s got a hefty price tag on it, too (laughs).

I thought, “Wow, this is fun.” And then, just talking to the fans at the opening. They’re really nice, relaxed events. They’re not like a show. They don’t have that intensity of a rock show. It’s nice that you can meet the fans that are interested and talk to them. I suppose a different kind of fan comes out. A lot of these art collectors are people who may not really know what I do musically. So it’s a chance to expand my horizons that way.

I’m waiting for 10 more guitars, believe it or not. We have two more shows coming up in the Washington DC area in June. But again, we’re hampered by the supply chain issues trying to get Ibanez guitars off of boats. You know, sitting off ports and so I can get them in here and paint them. Wish me luck on that one.

I know you have a big tour coming up in September that’ll take you around the States for three months, and then you head to Europe in 2023. You haven’t been on the road in two, three years. How are you feeling about going back out there?

That was the weirdest thing to happen after so many decades of traveling six months out of every year. When I averaged it out, we would generally do maybe six months at home or eight months at home, and then we’d be gone for a year and a half or two. True. But when I averaged it out, I realized I’m only home half of the year. It’s crazy. And it’s been a nonstop since 88. So, on the one hand, it’s really good to slow down a little bit and to attend to things. Even just technically, like I could bore you to death with how I’m working on one little thing that one of my fingers does that I’ve been trying to work on for years. Or how I’m working up using a different size pick for something. You know, guitar nerd stuff. Still working on tweaking pickups with Steve Blucher from DiMarzio and looking for new things to add to the finish of the guitars with Ibanez. But I really want to get back out there. Not only do I miss the playing on stage every night, but I miss hanging with other musicians. I miss being in different places every day and meeting the fans and walking the streets of different cities. I do love that. That is a component of my existence that I feel like has been squashed for a couple of years. So, I’m really looking forward to it.

But I have to say it has been really frightening to look at what could go wrong and that’s what’s kept us off the road — is what I see happening to other bands. I can’t honestly feel like I’m going to force my crew and my band out there if I don’t think I can keep them safe. Besides the fact that if we were stopped, it would be an economic disaster because we’re not like a big outfit that’s got three touring bands and we can substitute players at will. We don’t have a private plane. We play five and six nights a week and we go out for nine weeks. If we can’t complete it, it’s a hardship. It’s a bit frustrating because you see other people playing, you see the Rolling Stones doing it and you go, “Well, why can’t I do it?” And then you go, “Oh yeah, that’s right” (laughs). So it’s different.

I know what you mean. Wolfgang Van Halen was supposed to play here over the weekend, but he had to cancel because one of his band members contracted COVID and I think one of his crew guys did, too. That just complicates things, having to adhere to these protocols and then having to make sure everyone is well.

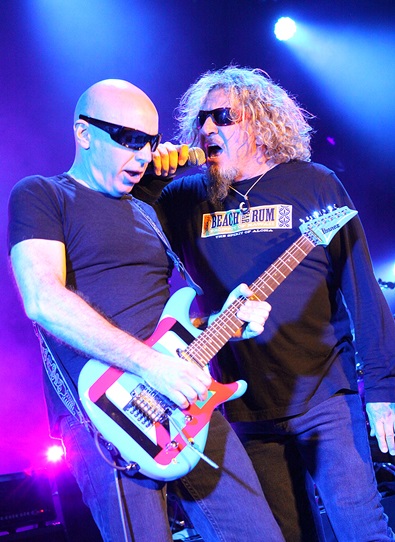

I think it’s important to point out that it’s economically devastating. Whoever’s paying in this case —Wolfgang, who’s paying the bills — he’s paying everybody’s salary and he still has to do that, whether or not he’s bringing in ticket money. I’ve spoken a lot to Sammy Hagar about this because he’s in a position where he can figure out a way to do it. He only books a few shows every few months. They do have private plane and they have protocols in place. He uses my tour manager, Alastair Watson, and he sticks to protocol like nobody else. They’ve been able to do it because if they did get stopped, they’d only be canceling one or two shows. So, everybody’s tour is different and has its own issues that they have to solve before they set foot out of their house.

Some people have to tour, they just have to. Otherwise, they can’t pay the rent. I feel for them and I applaud them for going out there and doing it. Most musicians are caught in this in-between world where they really need to get out there, but they can’t afford to get stopped. Like in the case of our European tour, for three years running, we could never get any of the protocols straight from half of the countries we were going to go to. We were going to be in 17 countries. And we couldn’t get anyone to agree on how long they going to stop us if one person tested positive. Would I get stuck in Bucharest for two weeks? The tour would not really ever get out of the hole for something like that. Let alone, we’d be in Bucharest — who knows what’s going happen there. Of course, the war broke out and it can get weird out there (laughs).

Are you guys in rehearsals and getting ready for the tour?

We definitely are going to get together in September and do our usual party rehearsal schedule, which is what we usually do. So by the time we hit the road, we’re not bored with each other. It’s always the danger when you rehearse too much because things happen in rock and roll. It’s really about learning how to respond to it. And if you get too prepared, then you get really upset when things don’t go the way you prepared them. I’ve always told everyone when we’ve gotten ready for a tour, “Take care of your world. We’ll meet up for a couple of days, we’ll go over everything. And then once the tour starts, we’ll start working it out and be ready to respond to the things that you know go wrong every night.” (Laughs) It just happens. I’ve been performing since I was 14 and it never goes according to plan. I think personal preparation is a really great idea. You play all the songs, you get your gear together, but then when you show up, you go, “I’m ready to improvise because that’s what I’m going to have to do.” That’s the reality of it.

I think it’s a unique opportunity. We have to put together a show that’s an evening with, which means we’re the only band. We do two sets and there’s an intermission. We’ve got two albums that we’ve never played on stage before, so we have to figure out a way to bring the best of those two albums to the stage. And then play the hits and play some obscure songs along the way and give the musicians a chance to stretch out and do a little solo bit here and there.

Is there a future for a G3 tour?

In the last few months, Steve Vai, Eric Johnson and myself have been interviewed together and we’ve been talking about it, how it would be a cool thing to do to get together. It would have to be next year. Steve just released a brilliant record and Eric’s got two really beautiful albums coming out in a month or so. So we’re all busy doing our thing, and we’ll all be hitting the road this year at some point. It looks like everyone wants to do something in 2023. We’re just not quite sure how it’s going shake out, but that would be great.

And what about Chickenfoot? I know it’s been a few years, but do you guys ever talk about doing a third album and touring again?

It’s a funny thing. When we talk about it, it’s always the unknown because we never really planned those records anyway. They just fell together in typical Chickenfoot fashion, which is like you get a phone call in the middle of the night and 24 hours later, you’re in the studio and hopefully you brought some songs and they get recorded (laughs). Very fast. And then weeks go by before you get back in to start working on them a little bit more.

I was just listening to the Chili Peppers album last night. A brilliant record. And Sammy’s got a really nice, really cool album that he recorded with his band, the Circle. I think that’s coming out in June. So, we’re all busy. We all have albums coming out this year or have just been released, and we’re going to be on tour for a while. I would have to say — outside of the odd chance that Chad or Sam get totally bored and they have two days off and they want to record an album — I wouldn’t see that happening until sometime next year. Next year winds up looking really booked, doesn’t it?

That’s the thing about Chickenfoot, right? You are all real busy and this is a side project. You have established careers. It’s not like a band that came up and you became successful together. It’s a super group. So this leads me to my very last question. You’ve had opportunities to join bands. You could have joined Deep Purple. But based on the fact that your solo career is your primary focus and you switch out players from one album to the next, would it be fair to say you enjoy the freedom of playing with a variety of other musicians as opposed to being in a set band?

I took my cue from those players that were laying the groundwork for the kind of stuff I do, like Jeff back. I saw the freedom that he had to play with interesting players that would inspire him, to do different things. I thought that’s really great. I love watching him live and I love his albums and he keeps you guessing and he’s always progressing as a guitarist. He just keeps going forward. I love that attitude of just moving forward all the time.

He’s not really hampered like a legacy band where they’re going to have to play their hits. Like when Aerosmith goes out, they’re just going to have to play those songs that are their hits. They got to play “Janie’s Got a Gun,” they got to play “Dream On.” They can’t do a concert without it. But Jeff Beck really doesn’t have to do anything he doesn’t want to do (laughs). He can say, “No, this is where I’m at right now, check this out. No one else can do it. I can do it.” (Laughs) I love that attitude. It’s a dangerous move. You miss all that input from a band and you miss the chance that you can go mainstream. It’s very difficult for Jeff Beck to go mainstream like Aerosmith or any other pop band where you’re talking billions of streams and TV appearances and all the awards, that kind of stuff. However, everybody knows and respects Jeff Beck as a player, as a musician, as a composer, and they wouldn’t dream of him changing his attitude. We like him being the iconoclast that he is.

I had that choice to make when Roger Glover asked me to join Deep Purple. I just thought, I’m Joe from Long Island. I don’t belong in this British royalty metal band. I knew I just didn’t belong. I was a big fan of Ritchie Blackmore and I thought I’ll never be able to rectify it. I’ll always feel guilty that I have to copy Ritchie and I didn’t want to do that. I’ve had friends who’ve had successful turns replacing famous people in bands. But I remember what they would always say at the end of it. I remember Steve Vai telling me once, “Joe, if you can avoid it, don’t ever replace anybody famous in a band because the fans — they never let you forget it. You’re always compared to the first guy, the original guy.” So I thought I’m going to take the chance. I’ve got a good relationship with my fans, and we’ll stick together and try to just make better and better albums.

I think you made the right decision.

Thank you.