By Shawn Perry

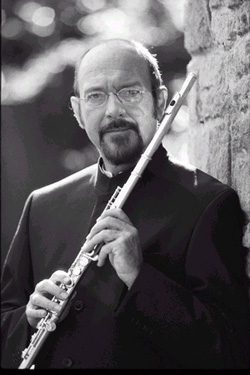

He is one of the most identifiable icons in the history of rock and roll. Balancing on one leg like a peg-legged pirate, his arm arched in the air as if moving in for the kill, codpiece and tights, wide-eyed and wild haired, flautist, acoustic guitarist, singer, and songwriter — there aren’t many who fit this description besides Ian Anderson, the leader and visionary of Jethro Tull. Of course, nowadays he isn’t quite as flamboyant, but his passion as a performer and musician remain a marvel to behold. And one would think that after so many years (35 and still counting), albums (over 60 million sold) and concerts (over 2,500 with more on the way) — Anderson would want to take a breather. Quite the contrary — a solo tour this fall finds him accelerating the pace. All this and he was able to work me into his day for a half-hour, transatlantic chat! He is truly a 21st Century Troubadour.

Unlike so many of his peers, Ian Anderson has weathered the storm with grace and reverence. Never one to dabble in the ill reputes of rock, he has instead experimented endlessly with musical ideas and concepts, ranges and forms. When he isn’t making music or tending to his wife Shona of almost 25 years, Anderson has astutely invested his time and resources into a number of life-affirming endeavors. He might be as well-known for being a fish farmer in Scotland as he is being a rock star in the rest of the world. Anderson is also supportive of the work of Spotlight Health, an organization specializing in celebrity health-issue awareness campaigns. He has been particularly vocal regarding the effects of Deep Vain Thrombosis (DVT), a medical condition attributed to air travel for long periods of time. It is no coincidence that the musician himself suffered from DVT and is now actively speaking out on how to prevent it.

At 8:00 AM on a Thursday morning, Ian Anderson called, just as I expected, from London, England. He was polite and accommodating as I angled to blow his mind with something original and captivating. No such luck — I’m sure he’s heard them all before. But he seemed genuinely enthused at the prospect of taking each question and turning it over to interpretation. While there were many things I wished to ask him, time was of the essence. So, I went with what I had and dove right in.

You finished another leg of the Living With The Past tour and you’re heading back out in a couple of weeks. How has it been going so far?

It’s been good. We’ve been all over the country. The southeast, the south, the north, the northwest, then down the middle. We’re kind of into the north central of the east coast of this leg. I’m coming back in October to do a few solo acoustic shows. So that will be four trips for me in America this time.

Living With The Past is an interesting overview of the band, and particularly your role as its leader and visionary. How did you come upon the idea of reuniting with original line-up?

The original band members of Jethro Tull circa March 1968 — that’s when I think we began as Jethro Tull. We’ve met each other over the years a few times, but never played together as a band. I have played with two of the guys — Mick and Clive — but never with Glenn since those early years. It seemed like a nice thing to have sort of a musical interlude going back to the original guys, and doing a couple of the songs that we had played in our early years at the Marquee Club — more like our early weeks — when we first started the band. They agreed to do it, so we got together at the end of January of this year. We got together in a little blues club in the midlands of England and did some things for the cameras. And we recorded it. It was pretty painless without much rehearsal — just a good bit of fun.

You also played a couple of songs (“Wond’ring Aloud” and “Life Is A Long Song”) with a string quartet. What inspired that?

Over the years, I’ve done quite a few things with groups of mainly strings, sometimes brass. In the 70s, there were many Jethro Tull albums where we used string sections and occasionally brass sections — the orchestral instruments as a whole. I’m going back to the very first time I worked with a string quartet, which was at the end of 1968 when we had a string quartet on the song “A Christmas Song.” So, you know, that’s kind of an area where I’ve worked in before, although I’d never actually played ‘live’ with a string quartet before because they, in the past, would overdub to backing tracks that we’d already done. You know — with my voice and guitar and they would play along with the tape. So playing with them live was interesting.

Actually, I was playing along with a string quartet a week or so ago in Germany when four members of the orchestra I had done a couple shows with came down to the front of the stage and we did those two songs live in front of a few thousand people. So, that’s something I’ve done before and something I’m sure I’ll do again. All those orchestral instruments are a lot of fun to play with, but I suppose there are particular problems in terms of pitch, tuning, amplification, and so on. But we try to get around them somehow.

I spoke with Martin Barre a couple of months ago, and asked him if there was ever a chance of a Jethro Tull reunion with other line-ups or other members. What’s your take?

Well, it would be very difficult, because many of them don’t play anymore. I was with John Evans, Jeffrey Hammond and Barrie Barlow last week. Sadly, it was to attend the funeral of Jeffrey Hammond’s wife, who died of cancer. It was, again, all the more apparent to me that here I was with three people I had played with, even before Jethro Tull. I think it was back in 1966 when we first played together. Those guys, when they left Jethro Tull…Jeffrey Hammond ceased playing immediately and never ever played again. That was in 75 or 76.

(laughs) So, it was a long time ago. And Barrie Barlow doesn’t play although he did say to me that he was going to start playing drums again. John Evan doesn’t play and can’t play. I think he has some kind of problem with his hands, so he is unable to play the piano. It’s actually not practical. So, the guys who joined after the original three and were in the band for most of the 70s — they just don’t play. It’s impossible to do when the musicians are no longer musicians, sadly (laughs).

On stage, you mention that Tull were once considered a ‘progressive rock band that made concept records.’ Do you think you could ever feel inclined to put another concept album together?

Well, the last time for Tull, I could especially say that Too Old To Rock And Roll was a kind of a concept album. It grew out of a concept of writing some music for a stage musical. But the three obvious concept albums are Thick As A Brick, Passion Play — which went to Number One o n the Billboard charts, only briefly. Then many, many years later, I made a concept album as a solo artist, which also got to Number One on the Billboard charts, an album called Divinities. It got to Number One in the Billboard Classical crossover charts, which is no mean feat. That means it probably sold something like 120 records (laughs). But there it was — at the top of the Billboard chart, so you can’t deny that.

If you’re doing a concept album and it’s instrumental, then it’s much more legitimate. It is removed from the pedantic and the awkward and self-conscious conceptual, lyrical album, which does seem a little overblown and a bit difficult. That’s why Thick As A Brick worked. It was a bit of fun. You know, pretending the lyrics had been written by a 12-year-old boy. That caught people’s imagination. It was a lighthearted send-up. It was a Mike Myers’ concept (laughs). Passion Play, on the other hand, was a bit serious and probably failed for a lot of people because it was too serious. It was too downbeat. It didn’t have the humor and the sort of self-deprecating standpoint of Thick As A Brick.

But Divinities was an instrumental album that was free as a bird. You can do things within the instrumental context without being misconstrued. It’s whole lot easier for Beethoven to make concept albums, if you can refer to his symphonies as concept albums, which I guess you could. But if he had started writing the lyrics, people would have been saying, ‘Hey Ludwig, I think you’re getting a bit too clever here.’

So, I guess chances are slim you’ll be restaging Thick As A Brick or Passion Play and performing them in their entirety?

I know there are a number of people who would enjoy seeing that. But I don’t think I have the stomach for it. Partly because I always have a terrible sense of all the things we leave out of a performance. Even though we change our set list, from month to month. If we were to go on and do all of Thick As A Brick, that would be half of a show, and it would cut down on even more of the things we couldn’t play. I’m not sure I would want to give that importance to one particular record. Again, I think you have to recall when that was performed live on stage in 1972 — all being only for a few months — it was done by a group of musicians who had a certain stage persona with a slightly more theatrical bent. Those aren’t the guys in the band today. Sure we could play the music, but I don’t think it would have that extra dimension that it had with Jeffrey Hammond, John Evans and Barrie Barlow in the band. For the reasons I mentioned before, playing again isn’t an option for these guys. It’s best left alone. If the Who want to do it, they can borrow it.

I just received the new Magellan CD on Magna Carta and noticed you appear on it. What do you think of the new wave of ‘progrock’?

There are a lot of great bands out there and I frequently listen to that stuff. I’m given a lot of records and a lot of would-be support bands send me their stuff. I hear a lot of it. There are some great bands in Europe doing the contemporary progressive rock thing. There are some that are pretty awful and there are many that are actually very good. Scandinavia is a real hothouse of progressive rock.

I guess I have a preference for those that aren’t trying to clone early Genesis, let alone King Crimson, Emerson, Lake and Palmer or Yes. And I guess you really have the big four there that I just mentioned. The archetypal, progrock band that preceded all of them was, of course, Pink Floyd who, back in 1967, performed songs from Pipers At The Gates Of Dawn. That was progressive rock music by any definition. Jethro Tull may have, at some point in time, been associated with that genre — but only if you apply that term ‘progressive rock’ in a loose and general sense, in which case you then have to embrace the likes of Radiohead as a more contemporary act, or perhaps some of the Seattle bands of the late 80s and early 90s would qualify in that way.

Some of the mid 80s bands — I mean, like the Police when they were in full swing, they were kind of a progrock band. Indeed, they had two musicians amongst them who were progressive rock musicians. Maybe not so much Sting. But as a band, they ventured into elements of progressive rock and then more sort of up-tempo, structured pieces. But by broad definition, there’s a lot of progressive rock. If we’re talking about that historical, defining genre, then we’re talking about King Crimson, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, early Genesis, Yes — that’s probably it. I think that’s why Jethro Tull always cultivated and kept a degree of looseness and more improvisation, which sort of kept us a little bit away from that structured and more musically refined kind of performance. Progressive rock — I would tend to use the broader definition unless we’re dwelling on the historical moments of some of the early 70s music.

EMI continues to remaster the Tull catalog and I had the opportunity to review the first three releases. What’s in store for the next batch?

That’s a sore point. Not a sore point with me so much, but a sore point with EMI because I keep promising (laughs). I ran across an old photograph to send them a couple of days ago, and some of the other missing master tapes the week before, and I still have to write the liner notes about the early days next week. There are three new releases planned for the end September, beginning of October, which are Warchild, Minstrel In The Gallery, and Too Old To Rock N’ Roll. There have been several more that have already been remastered, which I’ve got, and they haven’t been released yet. I was looking in my studio, and there are three or four others that I haven’t really checked out yet because we remastered pretty much everything in the early months of this year.

Last year, with the Beatles and Pink Floyd, there was an urgency to redo their stuff with the new generation of mastering hardware that’s been around now for a year or so, and is now fairly well proven. So, obviously the bigger and more sensational acts tend to monopolize the time at Abbey Road for using up all that remastering stuff. But we were in the queue, and we got some of ours done towards the end of last year and during the early part of this year. I would say we probably got two-thirds to three-quarters of the material that could be used is now mastered….is now safely on hard disc at 24-bit/96k resolution. In terms of digital quality, it is now safely stored and, for all intents and purposes as far as the human ear can now discern digital at that standard, is really indistinguishable from analog.

The latest digital technology is a great improvement. In fact, yesterday I just ordered a new 24-bit mastering machine for my studio because, I guess, from here on in, anything I do in the studio will have to be at 24-bit. I don’t really want to make any more 16-bit masters. Unfortunately, from ’86 onwards until now, they’re all at 16-bit because like everyone else I mastered them in the DAT format — a 16-bit format that really defines the quality of the masters from there on. People might say there’s no point in remastering anything from ’86 onwards because it’s already as good as it can be, but, in fact, there are substantial improvements that can be made from those original digital mixes. There are better converters, from analog to digital, digital to analog. You can actually get a better quality of 16-bit performance now than was the case a few years ago. But they’re never going to be 24-bit, put it that way. Unfortunately, I stopped using the analog tape, I think about in ’88. And so there are no analog master mixes. All the multi-tracks are analog, but the mixes were digital from then on. So it’s only pre-86 that there’s a real major benefit to be derived from remastering.

Have you ever considered doing any DVD-Audio or DTS releases?

It’s sort of inevitable, but I certainly wouldn’t be going back to do surround sound mixes of all Jethro Tull’s albums. I just wouldn’t. Not only would I not want to do it personally because it’s an enormous amount of work; it just wouldn’t capture, it would never sound the same. I actually don’t really like surround sound music. I’ve worked with the medium extensively. In the early 70s, we did three albums, which I mixed in quadraphonic, and I found it a pretty daft business, really! I decided it was a bit irritating in order to justify the medium — scattering instruments around in the audio field in such ways that makes people feel they don’t defile you for money by hearing some guitar solo coming over their left shoulder. What’s the point? It’s actually irritating acoustically, disruptive and confusing. I’m not a big fan of surround sound in that context.

In a live performance, there’s some justification for doing it. There’s some justification in wrapping some of the sound around the ambience, but people would listen to my mixes and say, ‘Oh they’re far too subtle, it just sounds like stereo with a little bit of reverb coming from behind my head.’ What the hell do you want? If you want to go and see some psychedelia in action, then I suppose you could surround sound mix some of that sort of music that might go with it. But most music I don’t think really benefits from it at all.

I’m all for improving the bit rate of …future music, DVD or whatever you want to call it. I think if we’re ever going to do some surround sound, I’ll probably limit it to a ‘Best Of’ album. I’m not sure I’d want to go back and tamper with the stereo mixes; you’ll never get it to sound the same again, that’s the thing. Mostly, analog tapes are unplayable; there’s simply no chance of going back and working with all the analog tapes. The oxide started falling off years ago (laughs) and they’re virtually unplayable now. I do have two or three that I did copy over to multi-track…for instance Aqualung, and I think, Thick As A Brick, and a few others were copied. We did some multi-track-to-multi-track transfers, so they ought to be good for a few more plays, but certainly we don’t have all the albums.

Let me ask you about your upcoming solo tour. I understand that you’ll be collaborating with radio personalities and having special guests, telling stories, taking questions from the audience…

Of course, it will be structured because anything like that, you know, you do have to have an underlying structure, not so much a free-for-all. The idea is to create a more intimate concert, focusing on more acoustic performances. I’ll have some other musicians with me, but not Jethro Tull members.

Will you be performing Tull songs as well as your solo material?

Absolutely. There will be some Tull songs that we’ll do in an acoustic format that will be quite different from the originals. We’ll do some of the Tull acoustic things that I guess I’m known for. There’ll be a few solo pieces. Yeah, we’ll have some audience folks involved, a couple of guests from each location, and a radio person or two who will co-present the concert. It’s really taking the sort of thing I do when I go to radio stations and play a few songs. It’s really taking that context into a greater live, public performance. It’s something I’m familiar with.

And what I like about it is the fact that it is very improvisational. Once you’ve thrown things open to people to have some input, whether it’s the co-presenters, the audience members or other guests, then no two nights are ever going to be the same. There’s always going to be some different stuff going on. And that appeals to me because it is a little bit on-the-edge-of-your-chair kind of thing. For me, as a performer and musician, I’ve got to be pretty alert and paying attention (laughs). It’s all going to be different people, different personalities, but still primarily a musical performance. Two-thirds music, one-third talk show — that’s the way to describe it.

Sort of like VH1’s Storytellers?

I’m not a TV watcher. I’m not a fan of music television of any sort, I’m afraid (laughs).

Ian, one last question: Are there any plans for a new Tull album or solo album?

There are certainly plans for some recording. I have a whole bunch of new songs I’ve been working on for the last few months, but unfortunately no time to get to the studio to start recording until probably November this year when I’ll be finished up with touring. One reason or another, I’m just very busy at the moment. I have a couple of other projects I’ve promised to do for other people, which unfortunately I’m way behind on. I’ll be working in the studio again from November through the first few months of next year. Yes, there’ll be a new album, I guess, scheduled for sometime during the course of next year — but whether it’s a Jethro Tull one or a solo one, I’m not really sure yet. I know the other guys have got some other plans too, so I guess we’ll talk about that during the next few weeks.