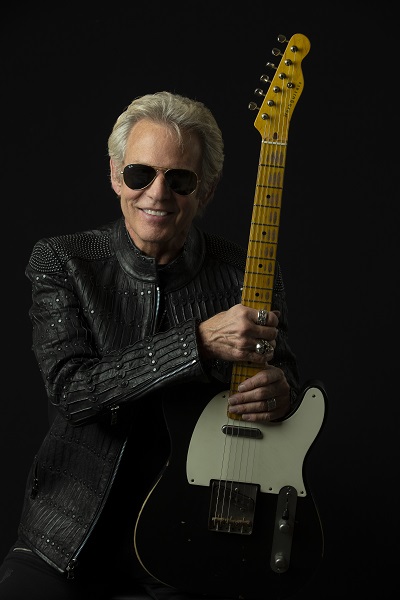

Former Eagles guitarist Don Felder has certainly made his presence felt in recent years — as the author of New York Times Bestseller, Heaven and Hell: My Life in the Eagles (1974-2001), as a solo concert attraction, and in 2019, issuing his third solo album overall, American Rock n’ Roll.

For the album, Felder hooked up with some of rock’s biggest names (Slash, Mick Fleetwood, Alex Lifeson, Peter Frampton, Joe Satriani, and many others), to offer up a record that showcases both his immense guitar and songwriting talents. Felder spoke with VintageRock.com shortly after the release of the album.

~

How did you approach American Rock n’ Roll compared to your previous solo albums?

My previous solo album, The Road To Forever, I played all the guitar parts on it — the electric guitar parts, the slide guitar parts, the acoustic, nylon string, I think I played mandolin…and zither! A bunch of different string stuff on it. And it came out really well — was really glad to have done that. But the thing that I felt lacked on that was the excitement of sitting together — much like Joe [Walsh] and I did for “Hotel California” —and putting together a solo, playing off of each other. The spontaneity, the energy that happens — when I sit down next to Joe Satriani, I had to step my game up, to put together the solos and the harmony parts for “Rock You.” It was a challenge. And working in and around other tracks, like Slash’s track, where I had to edit some of his stuff and make room for me to answer and play some of the solos, and also with Alex Lifeson, the same thing.

It as an interesting artistic challenge to be able to do that, and exciting. It also gave what I thought this record as opposed to my last record, a wide variety of guitar sounds and tunes. So I was able to do everything from playing nylon string guitar on “Little Latin Lover,” to playing slide guitar on “Sun,” and I played regular rock guitar with Satriani on “Rock You,” and playing guitar in and around Slash on “American Rock n’ Roll” — it was a real variety of sounds and artists that were there. Not only just guitar players, but drummers and bass players, too, that was just really fun to make each track sound kind of unique. As opposed to the last record, it had the exact rhythm section on almost every song — except for maybe one or two tracks had different bass players.

It’s interesting that you titled the album American Rock n’ Roll, as there’s been a lot of talk lately in the media about the state of rock n’ roll, and its future.

The current state of rock n’ roll has always been a constant mutation — from the old 50s that dates back to Elvis Presley, the Big Bopper, Buddy Holly. When it first came out as a genre coming out of the blues, into I guess what they would call a new version of pop rock, instead of blues rock. Every decade or generation continued to morph and mutate into various forms — all the way from the early rock n’ roll to the British Invasion, which really, they stole a lot from the early rock n’ roll days and the blues days, and came up with their own version that was something that was very familiar to American rock n’ roll.

I think the explosion at Woodstock, with the largest amount of people at any congregation to hear music for three days — I think it was close to 400,000 people there — really was a nuclear rock explosion, that was heard ‘round the world. The degree and fallout from that event went on to influence millions of people — musically as players, as writers, as singers. It just was a massive input into the migration and mutation of rock n’ roll. As a matter of fact, a lot of the people that are on this record were influenced by the artists of that decade — the late 60s/early 70s.

So, that title track from American Rock n’ Roll is about the history of migration from Woodstock —which starts with the first verse, talking about the artists at Woodstock — and goes through the decades of people who were not only influenced by that, but went on musically to become icons of their own in each decade. It was a salute and acknowledgement of the mutation and growth of rock n’ roll — up to current times. So, where is it going? What’s it doing now? I don’t know. But I think the spirit behind it all is here to stay.

Did you work with any of the artists in the studio together, or was it via file-swapping?

Both. Some players, like Mick Fleetwood, who was in Hawaii at the time, we sent him files and he went in his studio and did an amazing job. He sent us back I think two or three takes of him playing drums, that were great. Alex Lifeson was in Canada at the time – I would have loved to have been sitting in the studio with Alex to record that stuff, but we had to do it how we could do it. Joe Satriani and I were actually in the studio together, sitting on a couch, working out the guitar parts for “Rock You.” Sammy Hagar, I went up to his studio and he sang on the record. Bob Weir was in Sammy’s studio and sang on “Rock You” as well. Peter Frampton, I flew out to his studio in Nashville and we recorded his parts in Nashville, and he sang on a chorus with me on “The Way Things Have to Be,” and played a beautiful, angelic kind of Les Paul through a Leslie speaker. For the most part, I would say a lot of people actually worked in my studio — Steve Gadd recorded drums in my studio, Chad Smith recorded drums there, Slash recorded his guitar parts there. There was a minimum of file sharing, but in certain instances, there was no other choice.

Were all of these songs written specifically for this album, or were some leftovers from the past?

A little bit of both. The song “Sun” I wrote originally right after my first son was born. It was talking about the feeling that you get when you first look at your first born child. I actually played it for [Don] Henley and [Glenn] Frey, which was just a song I was working on that may be a candidate for the One Of These Nights record. They enjoyed it, but passed on it. It’s a guitar part that you have to completely re-tune the guitar into a different one other than standard tuning, which gives it a really unique kind of sound and tone. So I went back and re-tuned that, and after playing around with it, and thinking about how I could make this a little more universal — instead of just specifically about the birth of your first child. I re-wrote the lyrics, and it has a much more spiritual kind of connotation than originally conceived. And when I re-wrote the lyrics, I thought, “This is a nice feeling song, that should be on the record.” So, I re-did it.

When I interviewed you for The Yacht Rock Book about writing “Hotel California,” you said you had several other song ideas you presented to the band along with that song, and they chose that. Do you recall what other songs they were, and did they ever get recorded for either Eagles or solo albums?

One of them became “Hotel California,” and the other one became “Victim of Love.” So those two wound up on the Hotel California album. As a matter of fact, I was thinking I should go back and find that original cassette that has all those song ideas on it, and listen to it. There may be a few tunes that need to be re-polished and brought into the current time frame, and re-recorded. So, I might do that, now that you mention it.

Touring plans?

I’m probably going to be promoting this for the next 18 months — touring, doing press, interviews, television. Just continuing to draw attention to this particular project, because I think this turned out really well, and I’ve had so many amazing friends and associates and people that I know and have worked with before show up and play on this, that I am really honored and flattered that so many people responded in such a positive way — to be a part of this record. So, I’m going to work for at least the next 18 months, continuing to draw attention to this record, because I think it is probably the best solo record that I’ve ever made.

Any other plans beyond the tour?

I’m constantly writing — whether I’m sitting on an airplane writing lyrics, or a song idea I have that hasn’t been recorded yet, or riding down the freeway on the 405 in LA and have a melody idea, and pick up my phone and sing into that little recorder. I store these little pieces of song ideas, then go into my studio, pick up the guitar, and start playing guitar licks or looking for hooks, or progressions. Just seeing what comes out. And catching it as it flies by when you’re recording it, to me, is a really helpful way to take little snippets, and go, “Those two verses…those two bars right there were cool. I might play that a couple of times, and see if I can loop that together with a guitar lick.” Little ideas like that. So when I have the time to go into the studio and work on not just scratching ideas out like that, but taking those ideas and blowing life into them, and making them into songs and finished records. I’ve got lyrics, guitar licks, progressions, and a bunch of ideas started to look through, and use as I assemble these projects. Much like I did on this record. So, that’s my “time off.” (laughs)

When I saw you perform two years ago at Jones Beach in New York, you were playing a white double neck Gibson for “Hotel California” that looked identical to the one in the video from 1977. Was it the same guitar?

The original white Gibson 1275 double neck is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. And it has been there since 1998 — on loan. But it is currently on display on the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, along with Jimi Hendrix’s guitars, Jimmy Page’s double neck and Les Paul, Eric Clapton’s Blackie…it’s an unbelievable display of historical rock n’ roll guitars. At one point, they were going to call it The Most Influential Guitars In The History of Rock, but they decided to call it Play It Loud. It’s a shorter, sweeter version of that. So the one you saw me play at Jones Beach, I think I have somewhere around 15 white double necks, and I think five or six of them are the Gibson Don Felder Hotel California 1275s, where they took the original one out of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and they went over it exactly, and they cloned a duplicate copy — down to the cracks, scratches, cigarette burns, belt buckle rash, and all that stuff that the old one had. And I think they made 150 of those, which I think I’ve got five or six of those. So what you saw is not the original — the original is right now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.