By Danny Coleman

The Jets — are you kidding?” Legendary Guess Who and Bachman-Turner Overdrive guitarist extraordinaire Randy Bachman makes no bones about his favorite hockey team or his love for the city from which they, like him, hail.

In New York City on a promotional tour for his DVD/CD release Vinyl Tap: Every Song Tells A Story, Bachman took the time to discuss his roots, his career and what’s on the horizon. He also shared his thoughts on radio, the music industry and much more during an informal interview we had in a hotel coffee shop in Manhattan.

Bachman grew up in the 60s with the likes of former Guess Who bandmate Burton Cummings, and also counted Neil Young amongst his friends in a town which he refers to as, “the middle of nowhere.”

“Winnipeg is in the dead center of Canada,” he stated. “It’s the dead center of North America almost and it’s also the middle of nowhere. To go anywhere, it’s a good 400 mile drive to Minneapolis or to reach Thunder Bay; so you’re isolated. Luckily being at the top of the Great Plains, late at night with a little AM radio, myself, Burton Cummings, Neil Young, we’d have these little rocket radios with headphones in so your parents didn’t know you were listening to the radio and we would get Dick Biondi in Chicago, Wolfman Jack from somewhere in Mexico, KMLA in Oklahoma City, WNOE in New Orleans. I remember these vividly. Shreveport, Louisiana, when the nights were right, you’d get a certain station. You’d hear blues and R & B and music you never heard anywhere else, especially in Canada. The further north you got, the whiter the music got and the more sterilized and sanitized it got and we’d hear these incredible music records.

“I’d call Neil Young or see him up town and say, ‘Listen on Tuesday night to this spot on the dial, 89 and just go past the nine and you’ll hear this incredible music. It’s Stan the Record Man, it’s out of Shreveport. Louisiana or that kind of thing and you’ll hear the “Muddy Water’s Blues Special” and they’d play these three songs in a row.’ He’d call me back and say, ‘Yeah, I heard those songs; they’re incredible!’ Those were life changing for us and then, whatever was being played during the day, or whoever was touring, right below Winnipeg was Fargo, North Dakota and there was an Air Force base there, so when there was a tour of country western music people in a bus, they’d play Fargo and it was 90 miles up to Winnipeg.

“Dick Clark Caravan would play Fargo, North Dakota; with a caravan with Joey Dee and the Starlighters or Frankie Lyman and the Teenagers, up to play Winnipeg. Johnny Cash, up to play Winnipeg, so we got all of this stuff that was sent to the American armed forces base there in Fargo, which was really great stuff and whoever was coming to Minneapolis; the same thing. So I grew up hearing and seeing a lot of this really great music.”

Like most other struggling musicians, funds were limited but determination was not. Bachman spoke with fondness of certain situations where equipment was shared and bands worked together, sometimes as cohesive units, in order to perform.

“I played violin growing up but as a teenager I switched to guitar when I saw Elvis on TV. Neil Young moved out at about that time, I’m about two years older than him — I was about 16, he was about 14. He moved he started the band the Squires, I was in a band that was to become The Guess Who; we had the only amplifier in town. So when Neil Young had a chance for a gig, he’d phone Jim Kale our bass player, who owned a Fender Concert amp, that had four inputs, it wasn’t even a bass amp, it had four ten inch speakers with four inputs. So hope you had a mic, a piano, a bass and guitar and then a set of drums. Neil would call and say, ‘Are you guys playing next week?’ We’d say, ‘No’ and he’d say, ‘Can I borrow the amp? I’ll give you five bucks.’ So we would haul the amp to the community center, he’d plug in, his bass player would plug in and the drummer would just play unmiced drums, and they would play instrumentals at a dance; we kind of grew up that way.

“In Winnipeg in the 60s, there was probably about 150 bands in a small populous of maybe 300,000 people; all working not just in their basement. These were the working bands — there were guys dreaming to be working who were in their garages. The drinking age was 21, so if there was a high school dance, there were kids there from 13 to 21. They all intermixed, they all, older chicks would teach the young guys how to dance; it was really like a brother sister family kind of thing. It was amazing to play a dance. We’d have 12 or 14 hundred kids at the dance normally we’d have 200. These were like all older kind of kids; it was pretty much like a ‘Happy Days’ thing, like ‘Rock Around The Clock’ or those Bill Haley movies, you’d come and everybody would be there dancing. You’d play three hours and copy the juke box, and sooner or later, you’d try and write your own songs.

“Out of that came this dream — yes, we can make music; we each got two bucks each tonight, we got five bucks each tonight, we got ten bucks each and then, suddenly you’re making more than your dad who’s making fifty five bucks a week as an optician or a plumber or something and you say, ‘Dad I can do this, I’m making as much money as you,’ and he says, ‘Yeah, but son it won’t last.’ Then you pay off his house and buy him a car and he thinks it will last. So out of that came Neil Young, Burton Cummings from the Deverons who joined The Guess Who and then after that shattered and fell apart. Bachman-Turner Overdrive came out of that. Since then, the Crash Test Dummies, Tom Cochran with ‘Life Is A Highway,’ all these Winnipeg kind of guys all came through there. Monty Hall from ‘Let’s Make a Deal.’ David Steinberg was a year ahead of me in high school, he got thrown out for being the class clown, I got thrown out by the same principal for taking my guitar and not playing soccer. I would sit in the alfalfa weeds and play my guitar outside the school in the playground. We both got thrown out of the same school. Every time I see David Steinberg, he mentions O.V. Jewitt who was the principal. So Winnipeg was pretty much Liverpool in Canada and maybe North America.”

According to Bachman, once a band became somewhat established or amassed a following, certain industry people, radio, in particular, were quite willing to lend a hand. “The bands, the music, all of the DJs were helpful,” he explained. “They had one or two mics they’d take you into the radio station and you’d make a record, they’d play your record, it was instant Brill building in a way. There were no Carole Kings — it was just us goofs trying to write our own songs. You’d meet a DJ, you’d write a song, he’d record it and he’d play it that night and say that we were playing this weekend at Kelvin High School where Neil Young went to school or my high school where I went and you’d hear the song title and you’d play Neil Young and the Squires or Chad Allen and the Reflections and we became the Guess Who. DJs would play your stuff and promote it and kids would come to your dance because you were on the radio. It was really a wonderful, great time.”

That “time” has come and gone; today’s atmosphere is far different than the days of Bachman’s youth. Radio is vastly different, as is the music industry in general. Bachman concurs. “I think the saddest state of affairs is radio. They play such a small playlist. When I was growing up and you too, same thing — in an afternoon, you never had to change the station. You’d hear Tony Bennett, Patti Page, the Beatles, Elvis, the Del Vikings, the Ventures, the Shadows, Cliff Richard, Peggy March, Peggy Lee, do you know what I mean? You’d hear everything, “The Girl From Ipanema” played back to back with the Ventures “Walk Don’t Run.” Radio was eclectic, DJs had a personality. When they had three spare slots every hour, I remember DJs would play their own records that they found on their vacation or their cousin from Germany or England sent them a record from Scotland or something. That was personality. We listened to radio to hear great music and we listened to radio to hear Alan Freed and Cousin Brucie, Dick Biondi and Wolfman Jack, ”Hey baby…” These guys created a whole thing around it and they played music that fit their personality. It was just their own music that they discovered and were giving to us kids. Now every station is the same. I know that if I’m hearing something at 10 after two today, I’ll hear it at 10 after five today and 10 after eight today and the same thing tomorrow. So it’s too small a playlist, there is no personality.

“I have my own radio show in Canada called Randy’s Vinyl Tap. It’s on every Saturday for two hours. I play my own records; nobody tells me what to play. I have a theme for each show. So within a theme which might be girls’ names, like “Help Me Rhonda,”” Peggy Sue.” I can play stuff from the 40’s right to Lady Ga Ga, right to now to 2014, 2015. If my theme is motorcycles or names of cities, Kansas City — do you know what I mean? I can play 40 years of music and I tell a story behind every song and how I met every person — how I met Tina Turner or Brian Wilson, Ike Turner or whatever. Nobody tells me what to play, my fans write in the themes they want; car songs, plane songs, songs about devils and angels. I’m in my ninth year now and just got picked up for three more.”

Bachman’s eyes would dance when he discussed the formative years of his career and that of The Guess Who and BTO. Stating the stark contrast between the two groups without hesitation, he spoke with confidence to both. “No contest! They’re two different bands,” he said emphatically.

“One is a pop band; the other is a rock band. There is a real difference; the pop from the 60’s and very few bands did the transition the Beatles did well. From ‘Penny Lane’ to (hums the melody to ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’ and ‘Revolution’) the Beatles did the transition, so did the Stones, not as heavy as the Beatles, but the Guess Who were definitely a pop band. Our edge was ‘American Woman’ and then BTO was all like in your face, truck driving, motorcycle riding rock ‘n roll. The name Bachman-Turner Overdrive came from a trucker’s magazine. We were called Bachman-Turner for a while and people thought we were Brewer & Shipley and Seals & Crofts, two guys with mandolins, remember ‘One Toke Over The Line’ and Seals & Crofts doing ‘Diamond Girl’?” he laughed.

“We’d show up as Bachman-Turner and we’d be booked in a coffee house, so people with these little coffee things like that were this big (makes a circle with his thumb and index finger). We’d blow them off the table. They kept saying this was the wrong band for a coffee house and our label said that we need something to show that we play heavy music. So one day, at a truck stop, we saw a trucker’s magazine called Overdrive. So, I wrote them a letter and said. ‘Can we use this name for our band?’ They said, ‘Yes! You’re a band not a magazine or a publication, use it, it will help promote our magazine.’ When Fred (Turner) showed me the magazine, because he was into cars; the centerfold wasn’t a naked chick, it was the inside of a guy’s van with leopard skin and two little speakers and a little cooler with his drinks in it, the little light things and a centerfold on the ceiling of his van and that kind of stuff (laughs). We thought this is a really cool magazine, so we called ourselves Overdrive.

“Then when we went to take our first album picture in a studio outside of Vancouver, Mushroom Sound, where we cut a lot of stuff and where Heart cut all of their albums. We’re in this great big field and it’s sloped up, it’s a hill. The photographer is trying to get us in and he’s trying to get the sun on us and he’s saying. “Randy you move around, Fred move around.’ And as I moved around, I fell over something. It was buried in the grass and when prairie grass is this high, it all falls down in the rain and new grass grows through it. ‘Fred, I can’t move this thing, help me move it.’ We grab this thing in the grass and lift it up; we have a film of this. We lift it up, we lift it up, we lift it up and it’s this gigantic wooden gear that’s eight feet across and Fred says, “Oh my God, it looks like a Ferrari overdrive gear.” It was from a lumber mill in B.C. that they used to turn this thing to move the logs, so it wasn’t a metal gear, it was wood. So we held it up, it’s on the back of BTO One. So we’re holding up this great big thing and we’re looking through it and we sent it to the label and they go, ‘Oh my God, what a great logo — the overdrive gear and BTO in the middle, with the maple leaf to show you’re Canadian — that’s fantastic!’

“So, all that was kind of happenstance. I went back three years later and built a big house with all of my royalties. I had a great big room with all of my gold records; I had over 120 gold and platinum records on the walls and no light would fit in the middle. A wagon wheel looked like a dime because it was this huge room with big ceilings and all of the gold records on it. I went back to that field and that same wheel was there. I said, ‘Can I buy this wheel?’ The guy said, “I don’t even want it, give me twenty-five bucks and you can take it away.’ I took this eight foot wooden gear, took it to my house, I got tow truck chains, put it up, put lights on it and it became the chandelier in my record room, which doesn’t exist anymore but I’ve got pictures of it. Finding that gear was another magical thing that happened to the band.”

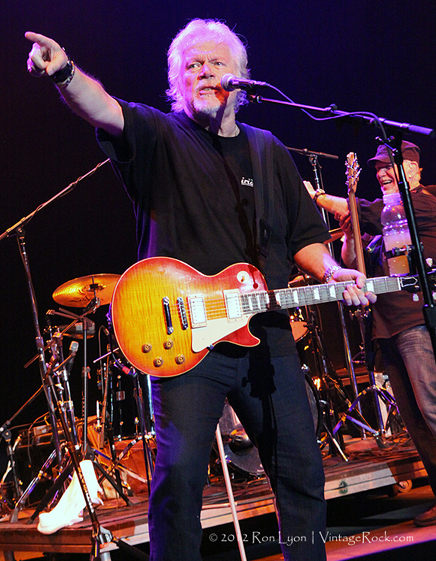

Fast forward to 2014, and Bachman has found himself on the road again; this time in a much different format from the hectic touring days of BTO. Vinyl Tap: Every Song Tells a Story has been released in the U.S, Europe and Australia. Here, Bachman elaborates eloquently on the stories told above, plus many more. This well produced, well recorded set is Bachman at his best. He is engaging, funny, honest and heartwarming with tales from the road and the studio. Standout sections are the origins of “American Woman,” which even now, decades after it first aired, its true meaning is revealed. Then there’s the piano part in “Takin’ Care Of Business” — the pizza delivery guy. Really Randy?

Bachman does such a fantastic job of relaying and recounting these adventures, one feels transported back with him as he effortlessly recalls his successes and failures; both of which have made him the man and musician that he is today. His backing band is set in a very cozy, home like atmosphere on stage and is phenomenal. The band is also accompanied by background footage from various time periods throughout Bachman’s career. Interspersed still photos and video footage lend a nice touch to this great soundtrack.

He readily credits the Kinks’ Ray Davies as the inspiration for this release. Bachman saw Davies’ Storyteller show at the Drury Lane Theater in London, England, and told him that he loved the concept and the show in general. Davies suggested that Bachman try having a show of his own based on his own back catalog of hits over his tenure. It was something Bachman instantly considered.

“People would call my radio show and want to hear my songs. I used to say, ‘I want my radio show to last, my program would be over on one Saturday if we went with only my songs.’ Ray Davies had said, ‘You could do twice as good a show. You’ve got two bands and twice as many hits as me; go back and put this together.’ Coincidentally enough, I go back to Vancouver and I get a request to play for the Canadian Cancer Society; a fundraiser, $5,000 a plate dinner. They want me to play but they don’t want me to blow the cutlery off of the table; can you play acoustic? I told them I’d tell the stories behind the songs and play a verse or two that way they’d get the song and get the story. I played it; I thought there would be talking because it was dinner. There was dead silence and they were all staring at me, I was feeling a bit self-conscience and then I’d say something funny and they’d all laugh and I thought, this is pretty amazing. Then I finished the night and they said, ‘If you recorded that we’d buy 10 copies and send them to our relatives all over the world!’ So I ended up doing this tour last year and my manager said it’s time to record it.

“(In) my hometown of Winnipeg at the Pantages Theater, where I used to see Ray Charles in, we did this show for a couple of days and they put out the DVD and released in Canada. The whole thing kind of organically came out and my manager would call and say, ‘We sold three copies this week, we sold five copies this week, we sold 10 copies this week, we sold a hundred this week, we sold a thousand this week, it’s Gold in Canada’ — and it’s like, ‘What?’ That triggered a release here in the States and it’s getting really good reviews and I am thrilled with the whole thing and idea. It’s like a looking back at my life kind of thing. It’s like an evening with Billy Joel so to speak, go see him in Madison Square Garden. If he took time in between to say, I wrote ‘Piano Man’ for the guy down the block who played piano or whatever, ‘New York State Of Mind,’ same thing. Every song has a story; you just have to get it out of the guy. The guy won’t do it unless the people want it. Sometimes they don’t want stories — they’re standing up drinking beer they want to rock ‘n roll. So these songs are adaptable to either.”

Bachman will be releasing a new blues album in 2015 and will be undertaking the next leg of the Vinyl Tap tour to close out 2014. He had some advice for young or up and coming musicians, pointing once again to his own experiences.

“I look at my career and I’ve had more failures than successes but people will forget my failures and tend to remember my successes. Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Babe Ruth were the home run kings but they were also the strike out kings. They struck out more than they hit home runs. In this business, they’re not going to look at how much you struck out but they will remember the home runs you hit. The dream is always the dream whether you’re 14 years old now or 14 in 1945 or 1960. Whether you want to shoot hoops or be Pete Rose or John Fogerty. The dream is always there, just the conditions change.

“If you feel it’s your gift from God or your parents or your creator, honor that. Don’t disgrace it by being a drunk or a drug addict. It’s hard enough to make it in life no matter what you choose to do but if you do drugs or drink, you’ll self-destruct. You’ll destroy your band, you’ll destroy your family, your marriage and you’ll destroy yourself. There is no plan ‘B’ — stick to plan ‘A.’ Find your dream, stick to it, do not take no for an answer. If somebody says, ‘No,’ say, ‘Excuse me,’ and either go around them or go over them. ‘I want to play Madison Square Garden; I want to play Radio City Music Hall’ I want to be on The Voice; I want to be on America’s Got Talent; screw you if you don’t think I’m good enough, I’m going to go see somebody else.’ Go over their head, go to their boss, do whatever it takes; all you have to be is better than the next guy.”

Randy Bachman’s Vinyl Tap Tour: Every Song Tells A Story is one of the most informative and entertaining releases today and a must for any classic rock enthusiast’s collection.

To discover more about the set, the tour or Randy Bachman in general, visit www.randybachman.com.