by Shawn Perry

You don’t typically get the whole picture of what Neil Young is all about in one sitting. The multifaceted musical chameleon is in constant motion — recording new and wildly different kinds of records, archiving his past, maintaining a whirlwind touring schedule, and heavily involved in a range of philanthropic and business pursuits that correspond with his unique vision and style. At an age when many of his peers are winding down and resting proudly on their accomplishments, Neil Young is an endless fountain of creativity and energy with no end in sight.

Leaving Crazy Horse tied up in the stable after 2003’s Greendale, Young went on to experience a series of ups and downs. He was hospitalized and treated for a brain aneurysm in 2005 that narrowly sidelined him for life. Ever the trouper, the singer-songwriter shook it off like it was no big deal, writing songs before and after the surgery for Prairie Wind. Apparently, he felt good and strong enough to play the entire album before a captive audience at the one-time home of the Grand Ole Opry, the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. The performance was beautifully captured by director Jonathan Demme for the 2006 film Neil Young: Heart of Gold.

That same year, he quickly threw together a hard rocking protest album with a surly, gospel feel called Living With War. Even as it received mixed reviews, Young decided to drive home his objection to the Middle East crisis by taking the record out on the road with his ever faithful cohorts Crosby, Stills and Nash. The Freedom of Speech 06 tour was a rousing success and another step forward in Neil Young’s never-ending quest for the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the whole fucking truth.

So, how do you follow that up?

Signs of a thaw in ongoing activity started to show when a concert from 1970 at the Fillmore East with Crazy Horse was released on CD, signaling the first rumbling of the eagerly anticipated Neil Young Archives project. Expectations for this all-encompassing history lesson seem to exceed a desire for new music, something Young hasn’t been short of for many years. While everyone from Bob Dylan to Led Zeppelin is faithfully revisiting their legacies, Young enlists the muse as his guide in most every instance. Even as a second live CD — this time a 1971 solo performance from Toronto’s Massey Hall — hit the streets, Young wasn’t about to let 2007 pass without a new studio album.

Perhaps as a way of acknowledging his past while embracing the future, Young summoned up Chrome Dreams II, the sequel to an album that never was, forgotten some time around 1976-77. The new album features three older tunes that never saw the light of day and seven new cuts. It’s a deceptive album that reveals a lot more about the singer and the spiral of songs and styles in which they should be played. The Continental Tour in its wake is giving fans as complete a picture as you could hope for.

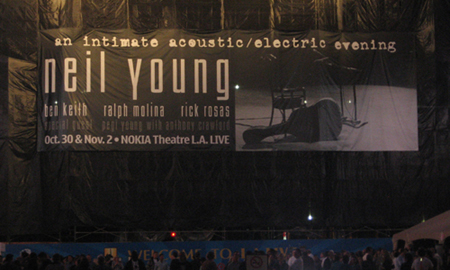

Seven days after Chrome Dreams II was released, Young and his band headed to Los Angeles for a two-day engagement at the brand new Nokia Theatre. The first show fell upon the same night as the L.A. Lakers’ season opener at the Staples Center, directly across the street. If you can imagine a tossed salad of basketball fans and Neil Young yucksters, you can understand the possibility for subtle mayhem. Actually, nothing much happened except parking was $20 and it was hard to get a drink. That certainly put a damper on things.

So I took a swift jog up the street to Riordan’s Tavern for a quick nip, then sprinted back past the packs of Wolfgang Puckers sucking on their $12 Coronas and designer mini pizzas, and slithered over to the will call window for my pass. The theater itself is like an extra large fish bowl with high ceilings and sky boxes, a 7,000 seater at the heart of a major gentrification underway in the downtown area. How it will survive in a town already crowded with concert venues remains to be seen. So far, the Eagles and Neil Young have given it a good debugging.

Pegi Young, making strides on her own with the recent release of her self-titled debut, started the engine up with a short and charming set and help from super lap steel guitarist Ben Keith, bassist Rick Rosas and guitarist Anthony Crawford (Young’s longtime guitar tech Larry Cragg also sat in for one number). At 9:15, Young ambled out onto a stage accentuated with oversized paintings, wooden Indians, hanging disco balls and studio lighting fixtures, and planted himself squarely inside a corral of acoustic instruments. A sudsy bottle of Amstel Light and a stainless steel canteen of who knows what nearby, the singer lazily adjusted himself, plugging the quarter-inch lead into one of his Martin acoustics and simultaneously fiddling with the harmonica neck brace, a device that only he and Bob Dylan seem to use with any regularity. And then, like a warm glass of milk before bedtime, Young eased into “From Hank to Hendrix” from 1992’s Harvest Moon and a blissful hush fell over the room.

By no strange coincidence, Young’s approach to the acoustic portion of the evening was reminiscent of the 1992 MTV Unplugged and VH1 Center Stage performances promoting Harvest Moon. Now as it was then, Young is never alone, even when he’s the only musician on stage. The acoustic circle is a ring of fire, perpetuating the singer’s intent of burning an impression onto each note (and this note’s for you). Occasionally, he steps outside the ring, makes a comment and shakes the spittle from his harp. Amidst the catcalls for this and that tune, someone blurted out: “You’re the king Neil!” The ever humble and agile Neil Young quickly responded with, “No, that’s Elvis…”

For an hour or so, he catered to the sentimental slobber of “Harvest,” “After The Gold Rush” and “Old Man,” shunned songs from the new record, and ventured into unencumbered territory with relatively unknown fare like “Sad Movies” (inspired by Norwegian tribute band, the Young Nails) and “Love Art Blues.” As a low-key political pundit, Young got in his digs during “Campaigner,” changing the line “Even Richard Nixon has got soul” to “Even George Bush has got soul,” which, despite drawing the expected hoots and hollers, could have potentially incited more confusion than inspiration. I have no doubt the singer works at keeping his audience ever entangled in the mysteries of his warped ideas. And he apologizes to no one for doing it in his own quirky way.

A short break and at 10:30, Young returned with Keith, Rosas and Crazy Horse drummer Ralph Molina along for the ride. Without bassist Billy Talbot and guitarist Frank Sampedro, the electric segment lacked the guttural raw thrashing that Crazy Horse (as a whole) bring to the table. But that’s never stopped Young from playing signature hip-shakers with the same fiery and intensity. The ring of fire is where ever Young wields “Old Black” (his trusty black Les Paul) — head down, literally stomping through each chord, feeding the tempo like a six-year-old in need of Ritalin. Everyone else just hangs on and enjoys the ride.

In between songs, the Devil from Greendale wormed his way to the front of the stage, placing and replacing paintings on an easel. Each painting depicted abstracts for the illiterates and titles of forthcoming songs for the rest of us. “The Loner” and “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere” were served up steaming hot, reminding everyone of how well developed Neil Young’s songs have always been, even in the earliest stages of his career. “Dirty Old Man,” the first one of the night from the new CD, may falter in the R&D department, but for a basic thump-along, it works on the same simple and visceral level as favorites like “Homegrown” and “Piece Of Crap.” Then along came “Bad Fog Of Loneliness” from the Live At Massey Hall CD, and the homespun goodness of “Winterlong,” refining the element and rectifying the muscle before the allegorical epic “Hidden Path” hypnotically pulled the audience down a slippery sloop for the duration of the trip.

An understated performance without pretense or worry, Young returned with a two-song encore. “Cinnamon Girl” rattled the floorboards and brought the mix n’ match masses in the orchestra seats to their feet for the remainder of the night. Settling behind a grand piano, Young became flustered with the floor monitor, remarking during the intro of “Tonight’s The Night,” the night’s final number, “If Bruce Berry were here, he would have fixed this fucking speaker by now…” It only made the show that much more special.

Celebrating his 62nd birthday days after the L.A. stand, Neil Young seems no worse for the wear, even when he wears the worse (at the Nokia, his pants were splattered with paint and his collared shirt was overly ruffled). It’s all part of the experience — the lackadaisical whimsy butting heads with pure, elegant indignation. The uncompromising, no bullshit world of Neil Young scurries through the muck, sidesteps the controversy, and accepts all responsibility for giving an ever perplexing reality a spot of sense with a dash of décor.