Within the sphere of popular music in Nixonian-era 1972, there’s an interesting hybrid of commercial acts. Teen idols, hard rockers, proggers, female belters, country crooners, soulsters — nothing is off limits. The biggest hit of the year would be the late Roberta Flack’s sleeper sensation “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.” What makes this track unique is Flack had actually recorded it for her debut album… three years earlier.

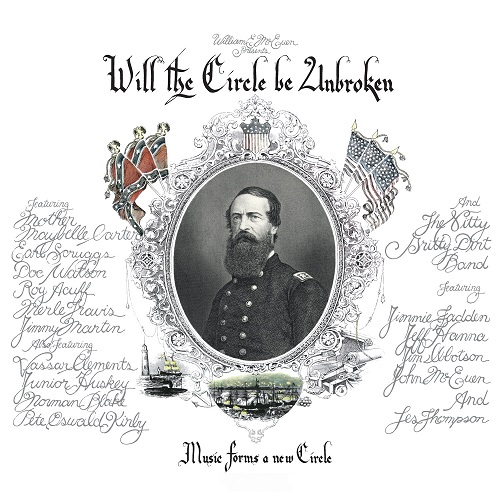

This wouldn’t be the only sleeper sensation of the year. Try the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s seminal three-LP album Will The Circle Be Unbroken. In this case, we’re talking about legendary acts within the country and bluegrass spaces finally getting their due recognition decades after their initial recordings. Hank Williams no longer becomes the lone defining archetype for this type of music.

When you take the time to listen to this album, you realize it’s one that is designed to influence and is birthed from influence. Though it would be released in ‘72, you could actually say that its origins trace back to the mid-1960s when a young banjo, guitar, and mandolin player named John McEuen and his brother Bill trekked to Nashville to see Flatt and Scruggs perform at the Grand Ole Opry. Earl Scruggs, a bluegrass legend, was a key influence for the banjo-playing McEuen. The show may have been sold out but the brothers managed to sneak peeks through a window, especially during a crucial moment in the show when Lester Flatt brought out Maybelle Carter (June Carter Cash’s mother) to sing her staple “Wildwood Flower.”

“The place went nuts. It was crazy; it was wonderful,” McEuen, now 79, recalled recently. “I said to my brother, ‘I got to meet (Earl) someday and maybe record with him.’ That was the set up.”

Fast forward to 1970. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band are riding high with the release of their cover of Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Mr. Bojangles.” The wistful, country-laden track would peak at number nine on the Billboard Hot 100, while the band’s accompanying fourth album, Uncle Charlie & His Dog Teddy, would reach number 66 on the US album chart. While in Nashville playing a homecoming concert at Vanderbilt University, McEuen would get to not only meet Scruggs, but the musician’s entire family as well.

“I heard this knock on the dressing room door, which was the girls locker room… I went and opened the door and there was the entire Scruggs family – Stevie, Gary, Randy, Louise, Earl. I looked at them and I went, ‘Oh shit,’ and I shut the door. I said, ‘I can’t deal with this right now,’” McEuen told me. “Fortunately, they were laughing. I opened the door a few seconds later after I tuned my banjo up. Earl came in chuckling. I met him and we developed a friendship.”

Six months later McEuen, who would eventually go on to play with everyone from Michael Martin Murphey to Steve Martin, would be driving Earl Scruggs back to his Colorado hotel when he popped a crucial question.

“I got up enough nerve to ask him, ‘Earl, would you maybe record with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band a song or two,’ and he said, ‘I’d be proud to,’” he said. “That was a big moment for me.”

With Earl Scruggs on board, the brothers McEuen would work on securing legendary country and bluegrass talent for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s next album, including Maybelle Carter, guitarist and singer Doc Watson, guitarist and singer Merle Travis, “King of Bluegrass” Jimmy Martin, and singer and fiddler Roy Acuff.

“We didn’t have the phone numbers, you know, and it wasn’t polite to ask for the phone number of somebody. It was much better to have a Scruggs call Jimmy Martin,” McEuen says. “Finally, two-and-a-half weeks after I asked Earl that question, Bill and I told the band we were going to Nashville to record.”

Will the Circle Be Unbroken, released in November 1972 and produced by Bill McEuen, would contain a whopping 37 tracks over three LPs. The album was recorded two-track in the studio in a mere six days in August 1971. It is not only a stellar primer of bluegrass and country music; it’s one of the best albums ever made.

“At least half of the songs were first takes… actually more like three-fourths of the songs,” McEuen recalled. “We rehearsed for it. We rehearsed for eight or 10 days and we went in prepared. I was having the time of my life because I was playing banjo and mandolin, so I was picking on practically every song. We knew with some of the people, like (Maybelle), that it was going to be best to have one take. Roy Acuff said to us, ‘Boys, you get it right the first time and the hell with the rest of ‘em.’ I always tried for first takes.

“The first person to record was Merle Travis and the first song we record, it actually took four minutes and it was done. The next one took two-and-a-half minutes and it was done. That’s what the first 15 minutes were like,” he adds. “My brother and I are going, ‘Oh my god, this is good,’ because everybody was good. By the time Merle Travis was done, he was done in about an hour-and-a-half. We scheduled four hours for him. So we sat around for a few hours and practiced and played back. It was great.”

Natural camaraderie (and chiding) between band members and legends is abundantly apparent on the album. The entire work sounds like a living room recording for entertaining friends. Very few recording snags occurred, according to McEuen.

“It was only difficult with Acuff on the first song because he wasn’t sure what them Nitty Gritty boys were gonna do. ‘I don’t know if they’re boys or old men; they’re all covered with hair,’ quoting him,” McEuen says. “We played him four cuts. He sat and he listened; did not move a muscle — just listened. When those four cuts were over… he said, ‘What kind of music you boys call that?’ Well my brother was looking for the right word and he goes, ‘Why hell, it ain’t nothin’ but country music.’ And everybody cheered. And then we went out and did “Wreck on the Highway.” When that was over, we were in because we delivered one of his signature songs in his signature manner.”

The genius of this album also lies in its spoken vocals, not just sung ones. In tandem with recorded songs, the album showcases fun and complimentary wordplay between musicians throughout. One example takes place within the first 30 songs of opener “Grand Ole Opry Song” where Jimmy Martin shouts out, “Earl never did do that,” when a banjo part gets flubbed.

“We planned a tape machine that was running really slow… to run all the time and to capture all the talking between the songs, which became a very important part of the album,” McEuen said. “It was a very clever thing to do. It breaks the fourth wall that isn’t there. It just added flavor — added in what these people were like. You needed to meet these people. As a record producer, Bill made a perfect decision there. His next chore was editing and sequencing the album so it would play in an interesting manner.”

The intention behind the album is reintroduction. Though the artists showcased perhaps weren’t labelled legends in 1971, the McEuen brothers set out to ensure that this label would apply to all album guests for the ages.

“Jimmy Martin was being ignored by the serious music industry. He knew this wasn’t being ignored anymore,” he said. “Maybelle Carter, in the Fifties and early-Sixties, the only job she could get was being a nurse in the general hospital. Flatt and Scruggs saved and gave her back her career… Country music had put her aside. Doc Watson – Merle Watson, his son, told me, ‘This is going to be good for Daddy because this music crowd is dying out and getting smaller all the time.’ That’s exactly what I wanted to do and what Bill wanted to do.

“I had heard Vassar Clements on several different records, I didn’t know it because they didn’t have credits. When Earl said, ‘I found a fiddle player that can handle the whole styles,’ I said, ‘What’s his name?’ He said, ‘Vassar Clements,’ and I had never heard the name. I said, ‘Earl, can he handle all the styles?’ And Earl said, ‘He’ll do.’” McEuen adds with a laugh. “I heard Jimmy Martin on records with the Osborne Brothers and Bill Monroe and I never knew he was in Bill Monroe’s band back then. When I found that out, [I said], ‘We got to get the word out that these people are great.’ That’s why their names are on the front of the cover.

I feel it foolish to call out specific track highlights because there should be no hopscotching around when listening to this album. Titles like these are standards and staples so if intrigued by any of them, grab a copy of the album and tune in: “Nashville Blues,” “Black Mountain Rag,” “Tennessee Stud,” “I Saw The Light,” “Sunny Side of the Mountain,” “Lost Highway,” and, of course, the album’s title track.

The album’s material selections proved a democracy among those who participated in its making. Each person was asked to give the McEuen brothers a list of “four or five songs” that they wanted to record.

“Earl wanted to play guitar on a couple of Carter Family songs so that was totally plausible. I learned how to play guitar from Earl Scruggs’ playing. And I put one of my instrumentals on there, ‘Togary Mountain.’ That was for Gary Scruggs,” McEuen said. “There was no direction from the other guys as far as the artist material. ‘Honky Tonkin’’ was perfect for Jimmie Fadden. ‘Lost Highway,’ Jimmy wanted to do.

“I knew this — day one, that this is good. This is going to stand the test of time,” he adds. “When we were recording ‘Tennessee Stud’ with Doc, I’ve got my headphones on and I’m listening and playing and I thought, ‘Man, this sounds like a magical old record.’ I felt like I was playing along with an old record – something I had dug out of the files that was 50 years old back then.”

Yet while the McEuens always had faith in the album’s potential and projected success, it proved to be a tougher sell for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s record label, United Artists, and its president Mike Stewart.

“I did the best pitch I ever did saying this music is going over at the college campuses,” McEuen told me. “I said, ‘There’s a thirsty audience out there waiting to hear about these people.’ Bill and I were trying to get the money to make the record. You can’t just go into the studio and invite people in. The record company put up $22,000 to go make the album. Twenty-two thousand in 1971 was still not a lot of money, not even to make a double album. We ended up making a triple album because there was so much material. It actually came in under budget.”

The McEuens also worked to ensure that the “business” aspect of the music business wouldn’t interfere with the album they were making.

“That didn’t exist in the studio. I felt more like it was 1927 and I was Ralph Peer. Nineteen twenty-seven was when Maybelle Carter first went to Bristol, Tennessee, with A.P. and Sara [Carter]. They laid down 10 songs for $50 apiece and they basically created country music that day. And here we were trying to make an old record. An old record is a jewel of a thing.”

The album’s title would be determined near recording’s end. For McEuen, the title bears a unique coincidence.

“I found out last year, several years after my brother passed away, that the first recording of ‘Will The Circle Be Unbroken’ was done in 1915 in England by a guy named William McEuen. I couldn’t believe it,” he said. “It’s like, ‘What?’, and here we are making this record against going uphill and having it feel like downhill. It was just really weird.”

Will The Circle Be Unbroken would eventually go platinum 25 years after its release. Two additional volumes would follow, one in 1989 and one in 2002. The length of time between album release and commercial milestones could be attributed to the initial difficulties in manufacturing the album, according to McEuen.

“It took about two weeks to make 25,000 units. And the record company was spending a lot of money on the manufacturing of this record. They only made 25,000 units. Well, when they sent out those 25,000 units, they were gone in one day because we got a bunch of advance publicity out there. So they had to order more,” he said. “It took a couple of weeks to get the records printed and pressed and another week to ship them. So that’s three weeks with no product in the market. And then 25,000 go out. Let’s say in the next week or two they’re gone. ‘Well, we got to order more.’ Another couple of weeks go by when they order more so it never did chart because Billboard would go, ‘Well, what did it sell this week? Well nothing. It didn’t sell anything.’ That went on for a year.

Despite the slow and steady approach, the album’s success always remained sweet.

“I got to give Maybelle Carter her first gold record. I couldn’t believe it,” McEuen told me. “‘Maybelle, here’s a gold record for that album which means it’s sold 500,000 units.’ ‘Why I’ll be, I never thought that many people ever heard my songs.’ And she meant it. I got to give Doc the platinum one but Maybelle was gone by then.

“It’s 50-plus years old. People are still coming up to me every show and saying, ‘I got that Circle album in 1972;’ ‘I got it in 1986;’ ‘I got this album in 1995,’” McEuen adds. “People have bought this record and it continues to sell. It’s amazing. One of the good things about this is that Les Thompson and I go on the road together still — Les was in the band — and tell the stories of the Circle album and the early Dirt Band along with the music.”

The only notable omission from the album is the presence of bluegrass maestro Bill Monroe. Initially opposed to taking part due to thinking the album would contain more rock instrumentation and sound, Monroe, per McEuen, would come to regret not taking part in the collective gathering that gave bluegrass its second life after the album’s 1972 release.

Simply put, Monroe admitted he made a mistake.

“I would have loved to have done “Molly and Tenbrooks.” It’s a Bill Monroe song about a racehorse. I wanted to record that one with him but it didn’t happen,” McEuen says. “Three years after the album’s release, Bill Monroe came up to me at a festival — I had gotten to meet him by then. He said, ‘Hey, John, if you ever do another one of them Circle albums, give me a call.’ He saw this beautiful album cover that he wasn’t on.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.