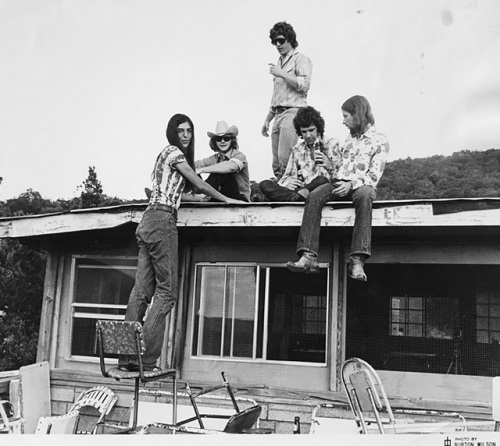

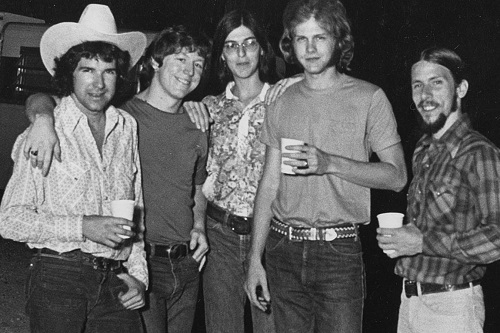

Photos courtesy of Bobby Earl Smith

ZZ Top is known as “that little ol’ band from Texas.” Yet in the early 1970s, that honor could easily have been bestowed on a musically tight, Austin-based quintet named Freda and the Firedogs.

Featuring members Steve McDaniels (drums), David Cook (steel and rhythm guitar), John X. Reed (guitar), Bobby Earl Smith (bass and vocals), and Marcia Ball (piano and vocals), the band would set Austin on musical fire across the city’s vibrant club scene, catch the ears of Tex-Mex artistic wizard Doug Sahm and legendary Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler, and record several seminal tracks at the renowned Robin Hood Studios in Tyler, Texas — all in the span of six months.

“I can’t imagine how much energy we had back then. It’s impossible to imagine,” Smith told me recently. “We were tight — we were so freaking tight.”

“We were definitely what was going on in Austin,” Ball, a Grammy-nominated blues artist and Austin City Limits Hall of Fame inductee, adds. “What was going on in Austin was gaining attention throughout the country.”

Fifty years ago this August, Freda and the Firedogs spent three days in Tyler (“the Rose Capital of America”) recording the tracks they hoped would propel them to superstardom. A mélange of classic country staples (“Make Me a Pallet,” “Fist City,” “Stand By Your Man,” “Jambalaya”), blues (“EZ Rider”), and twangy honky-tonk (“Cold Wind,” “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad”), the self-titled Freda and the Firedogs was assembled at a seminal time in country and western music. The year 1972 would see such renowned releases as the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will The Circle Be Unbroken, Stephen Stills’ Manassas, and Kris Kristofferson’s Jesus Was A Capricorn.

“The process? Well, we got up there and we got in the studio and just ran our favorite songs,” Ball said. “You say we made an album; I thought we were making a demo.”

But while the then 23-year-old Ball’s Louisiana-infused vocals and musical style collectively recalls Tammy Wynette, Loretta Lynn, and Bonnie Raitt, the album would not see the light of day until nearly 30 years later. Produced by Wexler, the band hesitated before signing a deal with Atlantic. By the time the signatures landed on the dotted lines, Wexler had parted ways with the label and the Freda tapes would be stored away.

“We did sign the contract. We took about six to eight weeks before we signed it … because we were going, ‘Well we want artistic control, we want more points, we want this, we want that,’” Smith says. “Wexler was telling us, ‘Look, the Atlantic lawyers will never agree to use the phrase ‘artistic control’ or put anything about that in the contract, but you can ask anybody on Atlantic, we never tell you what to do. We kept Wexler waiting at the altar.”

The band also marveled at how Wexler was keen to release the tracks “as is” on the renowned label.

“I didn’t care if it was a demo or a trash bag. It was on Atlantic Records and I wanted to put it out. I was chomping at the bit,” Smith said. “That said, there wasn’t dissention in the band. We were a bunch of hippies. We were a hippie democracy. I’m here to tell you hippie democracies in a band don’t work well.”

Fortunately, the story of Freda and the Firedogs has a happy ending. To get there, let’s go back to the band’s beginnings.

After moving to Austin from Louisiana, Ball would trek one night to local music dive One Knite where a group called Dub and the Dusters were playing. Having cut her musical chops in a rock band back in Baton Rouge, Ball would connect with band drummer Freddy Fletcher during a set break.

Fletcher just happens to be Willie Nelson’s nephew.

“(Freddy) said, ‘Hey man, I met this long-legged chick who’s from Louisiana. She turned me on to some good pot and she’s a singer, let’s get her up here,’” Smith recalled. “I said, ‘Freddy, we don’t do sit-ins, you know we don’t do sit-ins.’ I had a rule: If you let somebody sit in and they’re fantastic, you lose your crowd. If you let someone sit in and they stink the place up, you lose your crowd. Either way it’s a no-win situation. I don’t know why, I said, ‘All right, let’s get her up here.’ And I called her up here.”

Smith adds that, contrary to her modern day, more extroverted performance style, Ball was shy when she first took the stage.

“Marcia backed up to the very back where it was completely dark. All you could see was these two long legs sticking out,” he said. “I said, ‘What do you want to do?’ She said, “Me and Bobby McGee.” It was in our setlist. And we started singing it. My wife tells this story, when I got home that night, I said ‘I found the chick singer I’ve been looking for all these years.’ I mean she gave me chills. She still does.”

Though Dub and the Dusters would soon disband, Smith was quick to build a new band with Ball as a key member, despite “Me and Bobby McGee” being the extent of her overall country repertoire.

“I was from Louisiana, steeped in soul music, R&B, and New Orleans music — all the piano players, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis and Fats Domino, of course, and then rock and roll pretty much. Cajun music had been there but country had not been in my repertoire,” Ball told me. “We had Ray Charles’ country record at my house. But I loved it because I had been screaming rock and roll all that time and it was really the first singing I had done with melodies and pretty songs and harmony.”

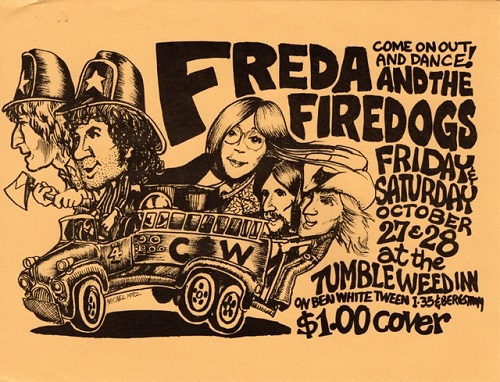

Enrapturing audiences at Austin venues like the Armadillo World Headquarters, the Split Rail, and the Dry Creek Inn, the newly christened Freda and the Firedogs would cut their teeth playing benefits for striking University of Texas shuttle bus drivers, according to Smith, all the while “schlepping” around an upright piano for Ball.

“We always get called progressive country or country. It wasn’t just country we were playing, especially if you saw us live. I mean we played everything,” Smith said. “Freda and the Firedogs started off playing to full houses. We started off full tilt boogie. Pretty soon we’re working six and seven nights a week. The band worked its ass off. We worked every night.”

“We were such hippies. I don’t know why we didn’t just take one night’s pay and buy Marcia a Fender Rhodes. We could have gotten one for a hundred bucks probably,” he adds. “But we schlepped around — I’m sure it weighed 600 or 700 pounds — an upright piano for every gig.”

The band’s fortunes would change further by April 1972, when Doug Sahm rolls into Austin fresh off the Sir Douglas Quintet (of “Mendocino” fame). Seeing the band perform at a club called the Hungry Horse, Sahm would soon sit in and ask Freda and the Firedogs to back him up at future concerts. They would eventually go on to record one rock song with Sahm, “Hot Tomato Man.”

“That worked like a charm for us. That opened tons of doors,” Smith said. “We’re getting on big gigs backing up Doug Sahm.”

“It seemed to all come together pretty quickly and a lot of it had to do with Doug Sahm,” Ball adds. “The scene in Austin had started to take off — this progressive country thing — and Doug had an instinct for where the next scene was going to be and what was going to be happening. Doug started coming to sit in with us and he would be at our shows and he was bringing people around. He brought Freddy Fender to Austin and we backed him up at a gig at the Soap Creek Saloon. That was before his big comeback with “Before the Next Teardrop Falls.””

Through Sahm, the group would meet Wexler, who would bring them to Robin Hood Studios to record with noted engineer Robin Hood Brians. Over time the group would also record songs with noted producer Huey Meaux. Like Freda and the Firedogs, those February 1974 sessions did not yield an official album release.

“It’s interesting, Tyler was dry — that means no liquor — and so the first thing anybody had to do was drive to the next town over to get beer,” Ball says. “You couldn’t believe how green I was. In my previous recording experience, I had worked for a radio station in Baton Rouge. I went in one day and sang the call letters for a station ID one time.”

“(ZZ Top) recorded their first record there the same year we recorded there. It’s behind his house. (Robin Hood’s) mom would come walking in from the kitchen with her hair up in curlers. The studio was just appended to the back of their house. It was incredible; just in this residential neighborhood,” Smith adds. “His was state of the art. The guy had magic ears. He was very odd — not in a bad way, just real different. But man, that guy was a good engineer. He was something else.”

Though Wexler was keen to get the band on Atlantic, conflicting tastes and personalities would prompt a separation between him and the label, changing the course of the band’s recording future, according to Smith.

“Wexler, he had signed Willie Nelson, he had signed Doug Sahm … but they didn’t go anywhere,” Smith says. “Shotgun Willie is a really great record, but it didn’t sell that much.”

Freda and the Firedogs would keep playing through, ultimately calling it quits after playing Willie Nelson’s 1974 Fourth of July picnic at the Texas World Speedway in Bryan-College Station. A live group performance at the Soap Creek Saloon, recorded in 1978, would eventually see the light of day thanks to Smith.

“Years later I realized the word got out that we were difficult to deal with. We weren’t really. We were just naïve and foolish. But the band had run its course. The phone wasn’t ringing at that point from the record labels,” Smith said. “It was a hell of a two years. I don’t consider it a failed marriage. It was just one of those things. Very few of those things wind up with a first-time band having a gold record on the wall anyway. But it was magic. It was a blessed music at a blessed time. I mean it was something else. We stayed friends all these years.”

Now onto the happy ending.

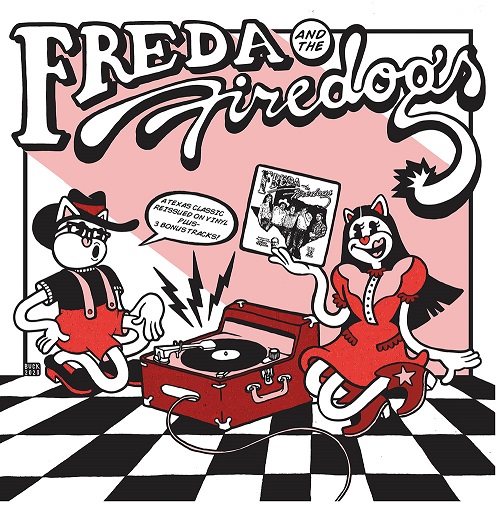

Realizing that he and Ball had lost their personal tapes of Freda and the Firedogs, Smith would ping Sahm to ask for Wexler’s phone number to see if perhaps he could help. Calls to Wexler would yield two key results — Wexler’s own master recordings of the album (“Two days later, it was on my desk; he FedExed it”), and Wexler’s approval to release the album. Freda and the Firedogs would be released on Smith’s own Plug Music label in 1999.

“It’s incredible to me that Wexler kept those tapes in his library and he could lay his hands on it immediately,” Smith says. “I called him and I thanked him for the tapes. He said, ‘Oh you’re more than welcome. Good luck with it. But you know what, you really fucked up when ya’ll didn’t sign that contract.’”

“He had to get his lick in,” Smith adds with a laugh. “I said, ‘I know it. I know it.’”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s new book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.