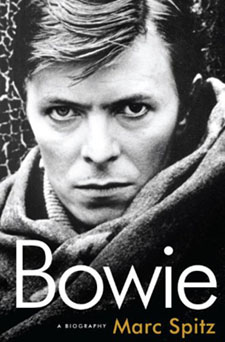

From Davy to David. From Jones to Bowie. Mark Spitz’s Bowie: A

Biography begins in 2005 at CMJ in New York City. CMJ is an annual

gathering that illuminates the latest and greatest offerings in the current

landscape of art and music. The arcade fire is a Montreal collective that performs

“Queen Bitch,” a Bowie composition from 1971’s Hunky Dory.

The crowd is mesmerized and the magic of song once again weaves its potent

spell. That this young band has come to the attention of David Bowie shows his

constant eagerness to be exposed to new sounds and ideas. It is a testament

to his consummate artistry and willingness to expand his musical horizons. Bowie

has been waxing poetic about this ensemble as of late and soon performs with

his eager acolytes at Radio City Music Hall. Filling his lungs with their anthem

— “Wake Up” — it is a moment of sheer bliss for all

who witness.

Bowie — the man of many masks, the ecstatic chevalier — was born

on January 8, 1947, in a suburb of London, post-war England, from working-class

parents. He was a shy lad, who, at a young age, developed an affinity for the

music of composer Frank Loesser’s musical, Hans Christian Anderson,

and, in particular, a song called “Inchworm.”

“’Inchworm’ is my childhood,” Bowie claimed in a 1993

interview. It wasn’t a happy childhood. In fact, it was emotionally cold and

exempt from affection. “Inchworm” gave him comfort and spoke to

his alienation through the mystical power of song. He claims it was also the

template for many of his best and saddest songs. It’s there on “Life On

Mars” and Aladdin Sane. Sad nursery rhymes were a recurrent

theme in Bowie’s vast musical vernacular.

In 1955, he found his next inspiration by way of American film icon James Dean,

an existential prototypical rebel of alienation. In Dean, Bowie had a kindred

spirit from which to relate. Shortly after James Dean, he came in contact with

the music of Little Richard, followed by Elvis Presley, and the rest of the

early rock and roll pioneers. This visceral, exuberant movement touched the

core of this emerging young artist’s spirit.

Along the way, he also became enthused by jazz. Such practitioners as John

Coltrane, Zoot Sims and Wes Montgomery gave him a taste of another aspect of

music possibility. He would learn the saxophone to discover this secret cabal

of sound. Discovering the writings of the Beat poets also had an enormous impact

on his fertile young mind, in particular the works of Jack Kerouac.

Through Kerouac, he discovered Buddhism. He found a sense of grace in chanting

and meditation, and became fascinated by Tibet. He then began to feast on an

eclectic array of ideas and sounds from the music of Simon and Garfunkel, and

the films of Stanley Kubrick to the writings of German philosopher Friedrich

Nietzsche and British novelist George Orwell.

Along the way, we meet Marc Bolan, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop and Mary Angela Barnett,

the future Mrs. Bowie, whose relationship is explored quite extensively in Spitz’s

fine tome. Interviews with former Bowie manager Kenneth Pitt, Siouxsie Sioux,

Camille Paglia, Dick Cavett, Todd Haynes, Ricky Gervais and Peter Frampton are

also featured.

We follow Bowie to New York, traipsing the East Village and dilly dallying

with Andy Warhol in uptown Manhattan. Then it’s Bowie on the Sunset Strip,

stalking the muse of old Hollywood and glitter rock. From there, it’s

Bowie the futurist, Bowie the Retroist, Bowie crooning like Sinatra with Bing

Crosby, Bowie in Japan doing the kabuki. And — oh yes — Bowie in

all his tortured glory as Ziggy the enigmatic glamorous alien.

Spitz examines the singer’s madness into cocaine, fueled manias and near

self-annihilation. Bowie next emerges as the Thin White Duke, wigwaming his

way through the labyrinth of selves. The consummate Freudian surrealist, there’s

Bowie in Berlin beseeching the ineffable, channeling David Lynch’s Eraserhead

in pure sonic, whimsical paranoia.

Bowie the actor next unfolds in a series of roles, set to stretch his artistic

palette. Cat People, The Elephant Man, The Hunger,

and Baal see our intrepid thespian on the hunt for new clues about

the human condition.

In the end, Bowie: A Biography shows us how the man

has transcended his nihilistic tendencies — maturing into an elder statesman

of song and sound, eschewing the razzmatazz with something more refined. As

the story continues, it’s obvious to the reader that Bowie has attained

a certain artistic dignity and a vision of something profound.

~ Lanny Cordola