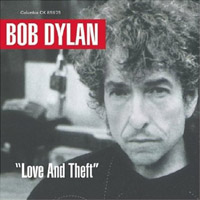

Bob Dylan has never been one to mire in his own past. In concert, he’s constantly altering the arrangements of his most classic songs in an attempt to avoid the pitfalls of staleness and redundancy. It doesn’t always work, and for a while there — especially during the mid 80s — Dylan looked as though he was just about to throw in the towel. But he rebounded and embarked on “The Never-Ending Tour” — solidifying a relationship with the best backing band he’s had since the Band. When he released Time Out Of Mind in 1997, it was as if Dylan had reinvented himself with his most introspective and ambient album in over 25 years. True to form, the accolades didn’t daunt his aspirations. He stayed on the road, made a guest appearance on Dharma and Greg, won a few Grammys, even won an Oscar — and took it all with a grain of salt. So much activity is testament to Dylan’s commitment to remain valid. Such is his ability to release an album like Love And Theft — a mesmerizing feast that defiantly explores the underbelly of America for all of its heartbreak, struggle and absurdity.

Rare is the artist whose 43rd album is as strong as his first. From the idle forays of Blonde On Blonde to the fiery intensity of Blood On The Tracks, Dylan has always known when to turn on the heat. For this outing, nothing is held back. Explorations into rockabilly, cabaret, vaudeville, blues, country, jazz and slumbering variations unveil yet another side of Bob Dylan. The shuffling groove of “Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum” is sumptuous enough to draw you in. Romantic ballads like “Mississippi,” “Bye And Bye” and “Moonlight” slip into comfortable melodies that align themselves with the painful woe of self-doubt. At every opportunity, Dylan digs in deep, applying his gritty voice to a terse, sometimes humorous inflection that bobs and weaves over a driving rhythm. In its harshness, Dylan’s voice becomes an instrument unto itself. It propels the rockabilly jump of “Summer Boys” while stoking the burning blues of “Lonesome Day Blues” and “Cry A Little.”

Dylan works beyond the basic framework, instilling a calculated, savory flavor on many of the tracks. The howling violin cross-examining the foot tapping, yet subtle ragtime jazz chords of “Floater (Too Much To Ask)” is a prime example. Dovetailing into a country bluegrass mode for a passionate reading of “High Water (For Charley Patton)” is yet another poetic page borrowed from Nashville Skyline. The ensemble breaks a sweat on “Honest Me” with guitarists Charlie Sexton, Larry Campbell, and Dylan himself chugging down a chord progression alongside a traversing, sideshow narrative — a keen example of the master’s penchant for tongue-in-cheek, in-your-face candor. When Dylan closes up shop with “Sugar Baby,” the lingering solace puts the whole affair in perspective. As it seems, things couldn’t be clearer for Bob Dylan as he once again takes flight behind Love And Theft, reaching beyond what is simply blowing in the wind.

~ Shawn Perry