By Ira Kantor

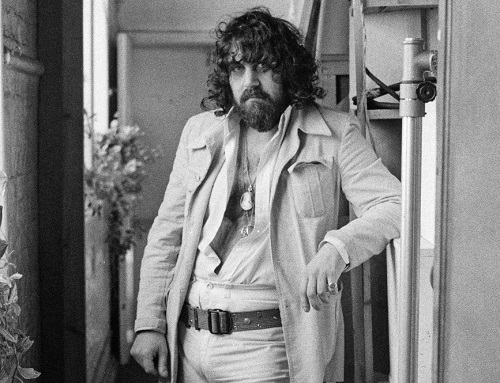

His photos depict a bear of a man with a steely eyed gaze looking as if the last thing he wants to do is speak.

But there’s a good reason behind that. Vangelis’ primary form of communication was his keyboards, pianos, and synthesizers. What his words couldn’t convey, his melodies and visual sense of past, present, and future could. Even in those rare moments when he would speak through his music (i.e. the terrific “Ballad”), technology would ensure his voice was riddled with mystique compared to accessibility. When you pinpoint Vangelis, you do it by his sound.

And over a more than 50-year career, Vangelis’ (born Evangelos Papathanassiou) distinctive sound would result in one glorious conceptual album after another (Earth, Albedo 0.39, China, Soil Festivities, etc.) even as he simultaneously shone through as the penultimate film soundtrack composer.

The tributes continue to pour in. As one-time Aphrodite’s Child bandmate Silver Koulouris writes: “My dear friend, no matter how high you go, for me as long as you live, you will be in my soul. This can not be changed … For me you are not missing, you are always near me, we will play together as we used to play and dream about the good moments of our lives.”

In my own case, Vangelis’ death at the age of 79 is hitting me hard, especially since several major events in my life have been indirectly scored by his work. The biggest two include:

- Being unable to sleep on my six-hour honeymoon flight to London given how floored I was listening to his 1975 Heaven and Hell To this day, I still can’t listen to the “12 O’Clock” section on side two without getting teary.

- The birth of my son, Freddie, who came into the world at 11:53 am on March 16, 2018. The song that was playing at the time of his arrival? “L’Enfant” from Vangelis’ Opera Sauvage

Ask folks if they’ve heard of Vangelis and they may instantly respond with references to British runners on a beach or Rutger Hauer’s quotable “tears in rain” monologue from Blade Runner. Yes, Vangelis would nab a number one Billboard Hot 100 smash with the theme (“Titles”) from Chariots Of Fire and earn the Academy Award for “Best Original Score” for the same film. Yet the scope of his talents and body of work go far beyond just these accomplishments.

Among his other achievements: making psychedelic prog a viable musical genre by complementing the soaring voice of Demis Roussos in Aphrodite’s Child; making history come alive by backing up Greek actress and singer Irene Papas (get hold of the album Odes now!); and proving he’s an artistic voice worthy of going toe to toe with Yes’ frontman Jon Anderson across four albums.

As Anderson describes in tribute: “He was my musical mentor … and a good friend… We created such wonderful music together … He was very funny to be with … Love and ‘light.’”

I previously asked Anderson about his collaborative experiences with Vangelis across the pair’s albums and other studio sessions.Over the years, Anderson would be a frequent guest of Vangelis’ solo albums (examples include side one of Heaven And Hell and on 1980’s See You Later). At one time, Vangelis was even in the running to replace Rick Wakeman in Yes.

“I visited the studio just to listen to him,” Anderson told me. “I spent time with him when he was working on a film score and at the end, he started to play a piece of music and I sang for the first time. To be in his presence was like wonderment and adventure and I started to sing. It was a song called ‘So Long Ago, So Clear’ and I just had to sing.

“We became great friends. It’s interesting how we created music because every track we did was the first take. It’s hard to explain, but he didn’t put down the music. He would start the tape, play, and I’d sing and at the end of five, six, seven, eight minutes, we’d stop. And then I’d say, ‘OK that’s that, let’s do another one.’ Then we’d do one a bit faster. At the end of the day, we’d have five or six pieces of music — sort of melodically chance music.

“I found I was actually singing things — singing spontaneously — especially with Vangelis. It was a happening whenever I’d work with Vangelis and I was always, always excited to work with him because it was the opposite to Yes.”

Anecdotes like these justify why I own more than 20 Vangelis albums. This doesn’t apply to every musician I listen to. But then again, there’s not many musicians who can convey instrumentally what others strive to do with voice. Improvisation, crescendo, ostinato, musical fearlessness — each of these elements fuel Vangelis compositions. And that’s what they should be called. They aren’t songs; they’re not tracks; they’re miniature works of art.

Plug into a Vangelis album and you see visions of utopia, dystopia, epic travel, precipices of human fear, the ability to conquer, and on and on. Even though he’s working with an instrument of the future, he seamlessly can harken back to sensibilities from long ago centuries and never seem cliché. A Vangelis album equates to a one-of-a-kind journey from end to end. Nothing is filler.

Not bad for a visionary who couldn’t formally read or write music.

Like a true storyteller, Vangelis’ concepts and synth-driven narratives are always riddled with color and beauty. Always game to take advantage of a wealth of soundscapes, Vangelis never tried to sound formulaic. It just happens to be coincidence that his sounds are that identifiable. In celebration of his talents and legacy, take some time and keep an ear out for these moments of musical brilliance:

- Hope shining through uncertainty on “It’s 5 O’Clock.”

- The world’s weight exemplified by simple keyboard notes on “Abraham’s Theme.”

- Glorious natural majesty conveyed on “Theme From Antarctica.”

- The rising buildup and burst of celestial beauty on “Alpha.”

- Catharsis and somber peacefulness emphasized in “My Face In The Rain.”

- The pomp and mechanisms pushing the future forward on “Spiral.”

- Lastly, the dazzling complexity and apparent triumph of “State Of Independence.”

- Side note: When this masterpiece was recorded by Donna Summer two years after the original version, it required a chorus of just about every recognizable 80s pop sensation to match Vangelis’ own musical virtuosity.

So let the photos depict a grizzled bear. Put the albums on and realize Vangelis is a genuinely lovely soul. He never needed flash or effect to establish his presence. Rather, he put his hands to work and, like a king, strove to create substance entirely from the ground up.

Which is why he should be treated like music royalty from here on out.