The Who

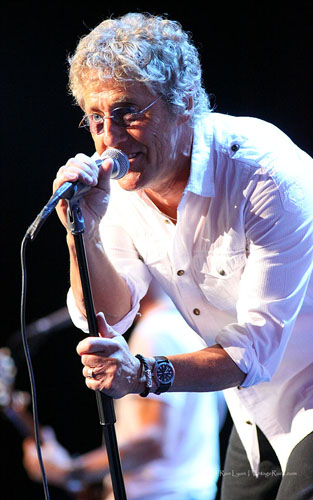

Tommy, the Who’s monolithic rock opera, may have sprung from the imagination of Pete Townshend, but its legacy transcends the guitarist’s own contributions. Perhaps the biggest effect Tommy had was on the Who’s capricious lead singer Roger Daltrey, the only member of the band who received no songwriting credit on the original 1969 album. Not only did Daltrey raise the bar as a vocalist on a majority of the album’s pivotal tracks, he actually personified Tommy — first on stage when the Who spent the better part of two years performing the opera live, and then in 1975 when he was cast as the lead in the Ken Russell-directed film adaptation.

These days, Daltrey still has Tommy on the brain. With Townshend lying low, making isolated comments about hitting the road with the Who in 2012, the singer decided to take the plunge by himself. He called in guitarist and Townshend’s brother Simon, guitarist Frank Simes, drummer Scott Devours, bassist Jon Button and keyboardist Loren Gold with the idea of mounting a full-scale interpretation of Tommy. At 65, it is likely the last time the singer will ever cover the entire span of the something that has had such a profound impact on his career.

Simes, who’s collaborated with Don Henley, Mick Jagger and Roger Waters, was the designated musical director — charting the music, arranging the vocals and essentially making sure the entire thing flowed. Daltrey would, of course, sing most of the lead vocals and Townshend would reprise many of his brother’s parts, with a few alterations and surprises added in for kicks. Simes told me during a break in the Tommy Reborn tour that the idea was to perform the piece as close to the original Who recording as possible.

Coming to Los Angeles, the show had already earned positive reviews in Europe and back east. For this reviewer, who saw the Who play Tommy, witnessing this performance firsthand produced a flood of thoughts, hopes and concerns. Would it be as heavy as when the Who did it at the Isle of Wight in 1970? Would they succumb to the campinesss of the movie or Broadway play? Most importantly, could Daltrey pull it off?

Aside from the heady videos plastered on screens behind the band and on the walls to the left and right of the stage, little in the way of theatrics was implemented. There would be no characterizations of Uncle Ernie, Cousin Kevin, the Acid Queen or Tommy himself — putting even more focus on the music. Shortly after 8:15, the musicians took their places and the twin-engine rhythm of “Overture” began to rise, magnificently executed by the five-piece band.

The seamless flow into “It’s A Boy” found Simes and Townshend locked in on the acoustics. Daltrey took the lead for “1921” and “Amazing Journey,” allowing you to close your eyes and admire the attention to detail. The footage on the screen gets some of its inspiration from the movie and Broadway productions, but only inasmuch as certain visuals have become as closely associated with the piece as the storyline and music. So you’re going to get a fair dosage of eyeballs popping in and out on both “Amazing Journey” and “Eyesight To The Blind.”

At times, you’re thinking it’s the Who playing better than they have in 35 years, as all the players stay true to the intricacies and nuances that have always given the album a component of warmth and character. Daltrey, fresh from throat surgery, hasn’t sung this strong in years. Magically, the classic songs popped and blossomed — from “Christmas” to the vocal calisthenics of “Cousin Kevin” to Simon Townshend’s “Acid Queen” to Daltrey in a crouch, delivering the kind of sinister read on “Uncle Ernie” that’d put the fear of ancillary retribution into Keith Moon.

There was little deviation, save for a remarkably appropriate guitar solo from Simes on “Sensation” and a slight “Acid Queen” tease that kick-started “I’m Free.” Gold also tinkled out a barroom flavored piano intro on the wistfully underappreciated “Welcome,” which earned more than a few kudos at the Nokia.

Daltrey’s Uncle Ernie returned on “Tommy’s Holiday Camp,” opening the gates to Tommyville and setting up for the grand finale of “We’re Not Gonna Take It.” As the audience stood and swayed during the “See Me, Feel Me” portion of the song, it became obvious that I was hearing a stupendously breathless rendition. What’s more was that Daltrey and his band played for over an hour without a break, and were far from done.

Introductions were made with Daltrey affectionately calling Simon Townshend “his brother” before reminding everyone that some of the band members were from California. He mentioned something about smoke causing problems with his throat and then announced the “fucking-about part of the show.” This consisted of a huge, energetic serving of Who classics, starting with “I Can See For Miles,” “The Kids Are Alright” and “Behind Blues Eyes.” Simon Townshend also got a chance to shine on a piece of buried treasure from Who’s Next, the rarely played “Goin’ Mobile.”

It wasn’t all Who though as Daltrey threw in “Days Of Light,” a jaunty little number about the weekend the singer co-wrote and recorded on his 1992 solo album, Rocks In The Head. There was also a spirited romp through Taj Majal’s “Freedom Ride” and a medley of Johnny Cash songs, intentionally sung in a lower register per orders from Daltrey’s doctor. This apparently opened the floodgate for throaty blasts of “Who Are You,” “Young Man Blues” and “Baba O’Riley.”

Just before 11, the singer dedicated “Without Your Love,” a simple and salty ditty from the McVicar soundtrack, to the audience. Then, armed with only a ukulele, Daltrey spoke about the final song of the evening, the morosely upbeat “Blue Red and Grey.” He explained how John Entwistle had arranged the horns on the The Who By Numbers version, adding that Townsend, who composed it, had no interest in performing it himself.

He dedicated it to both John Entwistle and Keith Moon — “two fuckers out there somewhere” — and bade the Nokia a grateful good night. As is customary with many Who shows I’ve seen over the years, Roger Daltrey, grinning ear-to-ear as he exited the stage, gave his all and did not return for an encore.