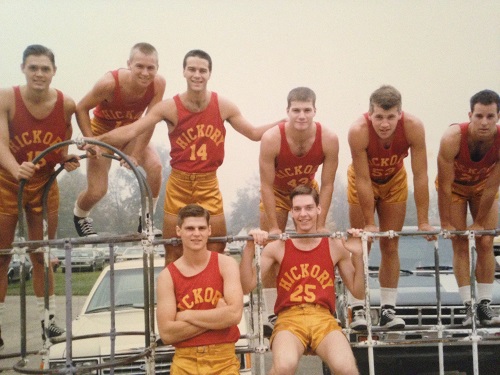

Photos courtesy of Brad Long

“It’s opening only in Indiana and it’s gonna open elsewhere in January, but I think they ought to open this one in New York and LA to qualify for Academy Awards because I think it’s that good…” (Roger Ebert discussing Hoosiers, 1986)

A good movie is one with an equally good score.

A terrific movie is one where the score overtakes your emotions as much as the acting on screen.

A movie for the ages is one where even if the score’s musicality conflicts with the ages depicted on screen, it underscores the storyline better than words ever could.

Remember Vangelis’ 1981 song “Titles,” the theme to the Academy Award-winning best picture Chariots Of Fire? This track has become so synonymous with running and slow-motion victory that it’s become laugh-out-loud meme worthy. But let’s probe deeper. The track, built around synthesizers, piano, and drum machine sounds like it’s from the future, but it’s designed to complement the year 1924. Yet Vangelis proves adept at using electronic sounds to convey the passion and intensity of the film’s central characters Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross) and Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson). “Abraham’s Theme” alone — mwah! His efforts would yield a Number One track in “Titles,” a Number One album, and an Oscar for “Best Original Score.”

The 1980s in particular offers other noteworthy examples. Tangerine Dream, perhaps the greatest instrumental prog band ever, would take the present day and make it sound like a dystopian future for a hat trick of dynamite soundtracks — 1981’s Thief, 1983’s Risky Business, and 1984’s Firestarter. Watch Thief (why it’s never on TCM I’ll never know) as James Caan’s pugnacious jewel thief gets corralled into the biggest score of his life. Listen to Tangerine Dream’s rising synth rhythms as Caan pulls off the heist, sits in a chair soot-laden and spent, and lights up a cigarette to celebrate. Instrumental magic!

There’s also Maurice Jarre’s brooding score to 1985’s Witness. Relying extensively on synthesizer here (perhaps in tribute to his Oxygene-creating wunderkind of a son, Jean-Michel), Jarre navigates the opposing worlds of secular and traditional as Harrison Ford’s John Book finds himself a stranger in a strange land learning to coexist with the Amish. Watch the barn-building scene halfway through and listen as Jarre’s bass chords convey the speed, sweat, and drive of the Amish as they raise a structure of seemingly mammoth proportions in just a day.

I’ll probably smack myself later for using this pun, but I can’t help it. By comparison, the score to the 1986 underdog film Hoosiers is simply a different ballgame altogether.

Never have I heard a score so beautiful, so evocative, so uplifting that I well up every single time I listen to it. It’s a study in modern versus classic — a soundtrack that seemingly builds off of Vangelis’ electronic aesthetics but harkens back to the golden 1950s era of epic. It’s Ben-Hur in basketball shorts and Converse sneakers. From the opening sequence and credit roll, the sounds you hear never leave you.

And in the wake of legendary actor Gene Hackman’s recent death at age 95, it’s become my go-to musical staple once again. Whenever I need to listen to something inspirational or something that makes a hard time seem not so bad, this is the piece of music I turn to most.

The only way to not spoil the movie for you is to not offer any context around that but I won’t be doing that here. I will, though, try to give as brief a synopsis as possible. Disgraced former college basketball coach Norman Dale (played by Hackman) heads for Indiana in 1951 to become coach of scruffy high school outfit, the Hickory Huskers. His style and way of playing the game — followed by some hard losses and enlisting alcoholic (and former hoops star) Wilbur “Shooter” Flatch as his assistant coach — rub town residents the wrong way and threaten his tenure as coach. Fate intervenes when Hickory’s star player announces he’ll play for the team if Coach Dale gets to stay. The ayes have it; the team becomes an eight-man Cinderella roster; and they go on to win the state championship.

Side note, this is one of my all-time favorite movies, driven in large part by watching it with my dad seemingly on repeat when I was a kid.

But none of this is meaningful without Jerry Goldsmith’s brilliance as a composer to help the dramatic pulls and tugs and ultimate victories come to life. Combining synthesizers with symphonic orchestra, Goldsmith makes this team one we root for — when they hurt, we hurt; when they win, we revel. Goldsmith, the man who gave us such scores as Patton, Chinatown, Logan’s Run, Alien, and Gremlins, takes his best shot here and while he doesn’t win an Academy Award for this score (even though he damn well should!), he transforms a storyline based in the past to one that sets the standard for how all future sports movies should be made.

“We weren’t privy to all of the score and the music and everything going into it when we were filming. I think I actually heard it maybe at one of the first premieres,” says Brad Long, 62, who plays Husker Buddy Walker (Number 14) in the film. “I’m sure I’m a little bit biased but whenever you hear it, you know right away it’s the background of Hoosiers. I think even if you’re not a basketball fan, you know that Jerry Goldsmith was quite a composer and quite an influence on other movie soundtracks.

“He knew what he was doing, and I think it’s stood the test of time,” Long adds.

Following news about Hackman’s death, I rang up Long, a sales representative and motivational speaker based in Whiteland, Indiana, to discuss his impressions of Goldsmith’s score, as well as his experiences in working with the two-time Academy Award winner on Hoosiers. After playing basketball in both high school and college, Long joined the film as a Husker at age 23.

“You’re right, it’s more of a ‘modern’ score rather than something that might have been indicative of the ‘50s but I don’t know that — as we get older — people even think about that,” he told me when I mentioned Goldsmith’s innovative way of using modern instrumentation to vitalize a story from an earlier era. “Especially the younger kids — they probably think that was the music from that time period.

“I just think — being a part of the actual filming part of it — that when you put the basketball action to the music, over time you sort of associate the two together,” he adds. “As far as emotions, to me, it sort of gets me going — kind of like you think of some of these medleys that they play at NBA games now to get the crowd going. It’s sort of similar to that. I’m sure partly because I’m intrinsically involved in the film, if I’m ever driving and that score happens to come on or I hear it somewhere, it takes me right back to filming.”

Goldsmith would be nominated for an Oscar for his Hoosiers score but lose to Herbie Hancock for Round Midnight.

Besides the use of synthesizer, Goldsmith employs a genius tactic to put us in the gymnasium with the Huskers. He uses drum machine style percussive beats to reflect a basketball dribbling on the parquet floor. It’s not always a steady beat, but it’s a constant reminder that the ball must get to the basket and the clock is always ticking down.

It’s a brilliant tactic — just watch the nail-biting scene where shorter player Ollie McLellan (played by 18-year-old Wade Schenck) has to nail two free-throws to secure Hickory a crucial victory. Goldsmith’s beats pound in your brain as you see the determination (and fear) in Ollie’s eyes. He sinks both free throws — underhanded — as Goldsmith’s brassy blasts capture the town’s joy and Dale’s moment of relief.

And that euphoria shines through again and again as the main theme from Hoosiers. It shines when Hopper’s Flatch has the boys run a picket fence play to score the winning basket in one game (Coach Dale urges the ref to toss him from the game so Shooter can prove himself and get a second chance at redemption). It shines when star Husker Jimmy Chitwood (played by Maris Valainis) returns to the fold and sinks basket after flawless basket.

And it especially shines in what is one of cinema’s greatest five-minute moments of film. Hickory, backed by Goldsmith’s Hoosiers theme, comes from behind to tie the game of the state championship with 19 seconds left, playing in a gym nearly 20 times the size of any they’ve ever played in. Hackman devises a play to make Jimmy a “decoy,” so another player can sink the final shot. The boys hesitantly pull back as Hackman questions their intentions. Finally, the stone-faced Chitwood, ever so slightly letting his guard down utters his final, immortal line of the film: “I’ll make it.”

The game’s final seconds tick down in slow motion. Chitwood hurls the jumper as Goldsmith’s ostinato builds and builds. When the ball swishes through the net, there’s a cymbal crash, those jubilant horns, and a dam-breaking of emotions. Flatch (the only acting role Hopper would receive an Oscar nom for) jumps up and down from a hospital bed in pure ecstasy; town residents hug one another and whoop and holler. Even Coach Dale allows himself a smile at this David versus Goliath chapter in his life. But you also see the pain of the other team losing; your tears fall as you celebrate with one side and sympathize with the other.

There’s no words, only music. Goldsmith’s score is titanic and, like the players on screen, it’s riddled with nothing but heart.

Hoosiers, a film no one thought would see much success outside the Hoosier State itself, would gross nearly five times its production budget — a situation Long describes as “a pleasant surprise.”

“It was our first film,” he recalled. “I always tell people that most sports films, they look for actors who they hope can play basketball or football or whatever the sport movie is about. This one they looked for basketball players and hoped they could act. They took a chance on us, but the writer [Angelo Pizzo] and director [David Anspaugh], I think by design, didn’t give anybody too many lines so that they wouldn’t be exposed. It was a lot of fun to be part of that. I think if the movie would have been about ping pong or bowling, I might have been out of my element. But I played high school and college basketball as did most of the other players on the team so we were comfortable with that part of it.

“We got good tips and advice from the director and Gene Hackman. They never really told us what to do,” Long adds. “We could make our own choices, but they would advise or give suggestions which I thought was really helpful and kind of took the pressure off. (Gene) was very much willing to learn what it meant to be a high school basketball coach. He had never played that role before. We went to some actual high school practices before filming and so I always admired that, that he said, ‘Hey, an old dog can learn some new tricks.’ I thought that was a pretty interesting way for him to humble himself to learn about that role.”

Long also revels in the memory of knowing that Hackman’s favorite part in Hoosiers is when Buddy is told to guard and stick to his man like chewing gum, imploring him to tell him what flavor he is by the end of the game. Walker, a gum chewer throughout the movie, returns to the bench after fouling out to find his coach simply gesturing at him until he says, “It was Dentyne.”

“What makes that scene work is the look on Gene’s face. He’s amused that I took him that serious,” Long told me. “I’m 62 years old and I’ll be having lunch somewhere and somebody will come up to me and say, ‘It was Dentyne.’ That’s kind of what I’m known for. And I’m a gum chewer in real life so it fits. I guess I was typecast.”

Goldsmith would pass away in 2004 at the age of 75. He would receive 18 total Academy Award nominations in his lifetime — winning only one Oscar for his score for the horror movie The Omen.

A truly poetic element of Hoosiers lies in its ending (sorry, I’ve given up on spoiler alerts by now). After the Huskers claim victory, the camera then dissolves into the Hickory gymnasium where a little boy shoots baskets. The camera slowly works its way up the wall, landing on a team photo as Hackman’s voiceover permeates the scene, ending with the line, “I love you, guys.” Goldsmith’s melodies trickle down to simple sustained notes. The memory is one to be remembered for the ages — similar to Hackman’s own legacy as a one-of-a-kind actor.

“He lived a great life,” Long says. “He was 95 years old but having said that, it doesn’t matter what age you are — it still hurts when you lose someone… And he was our coach.”

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com. Ira’s book, “Hello, Honey, It’s Me”: The Story of Harry Chapin, is available for purchase here.