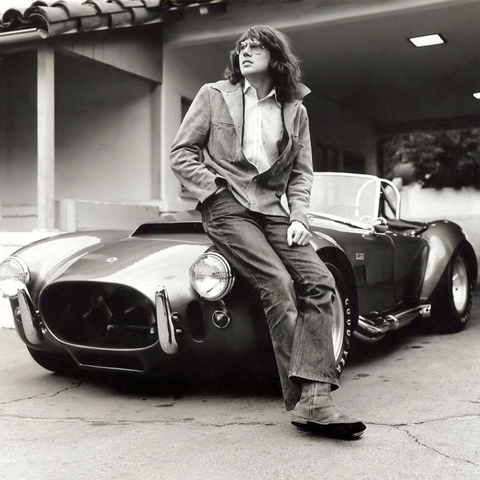

Photo by Henry Diltz

“You don’t mean to suggest that someone

would criticize (‘MacArthur Park’)?

I mean, my God! (laughter)”

– Jimmy Webb, March 2018

Based on its compositional structure alone, “MacArthur Park” should be deemed the greatest song ever written.

A stunning marriage of symphonic sounds and unbridled emotionality, the seven-minute, 25-second musical epic and its four unique movements remains ahead of its time, thanks to the genius of its composer, Jimmy Webb. Numerous interpretations have kept the now 50-year-old song relevant: Maynard Ferguson blasting the tune to the rafters; Donna Summer making it smolder then dance; “Weird Al” Yankovic spoofing it yet keeping its integrity intact; even Webb himself stripping the song bare but making it sound just as harrowing.

Yet one bone of contention continues to polarize listeners — its unique and enigmatic lyrics. Are they meant to be taken at face value? What do they actually “mean?” “Why leave a cake out in the rain?” Let’s also not forget Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Dave Barry dubbing the song the worst one ever written in his “Book of Bad Songs” more than 20 years ago.

While Webb maintains he’s “heard everything” and is “exhausted on the subject” when it comes to criticism about his masterpiece, that one still stings.

“I take issue with that,” Webb told me during a recent interview. “I think ’96 Tears’ by ? and the Mysterians … was the worst song.”

In the film “What About Bob?” Bill Murray maintains there are two kinds of people in the world – those who love Neil Diamond and those who don’t. When it comes to genuine music appreciation, I feel the camps can be divided into those who love “MacArthur Park” and those who hate it.

Personally, I love it. In the months leading to this column I listened to the song an average of twice a day. It’s still a stunning achievement regardless of whose voice makes Webb’s words come alive. While I’m particularly astounded by Ferguson’s interpretation of the piece, its greatest voice belongs to the one who helped the track ascend the heights of popularity the first time around — that of acclaimed actor Richard Harris.

In 1968, Webb and Harris saw the unconventional song not only top the UK singles chart but also nestle at the #2 position on the Billboard Hot 100. As a result, Harris’ accompanying album of all Webb-written songs, A Tramp Shining, would be nominated for an Album of the Year Grammy.

“Really Richard Harris – who was unstoppable — he became the driving force behind the record and the album project, which I think surprised a lot of people — what you could do with a kid from Oklahoma and an Irish actor,” Webb told me.

Webb, currently on tour and celebrating the recent release of his terrific, anecdote-fueled memoir The Cake and the Rain, is best known for other classic songs of the era: “All I Know,” “Wichita Lineman,” Up Up and Away,” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” included. If you’re like me, you’ll be amazed by the fact that “MacArthur Park,” which sounds as if it took months to compose, was formulated and assembled by the then 21-year-old in mere days.

As Webb recounts in his memoir, noted producer Bones Howe assigned him the task of creating a lengthy, classically-inspired piece for hitmaking group The Association, then riding high on the charts with seminal tunes like “Along Comes Mary,” “Cherish,” and “Windy.” They also happened to be Webb’s favorite band at the time.

Diving into both his memory bank and canon of artistic influences, Webb set about crafting one of the most successful songs ever — though no one knew that at the time. The sequence of events then occurs as follows, per The Cake and the Rain: Webb plays “MacArthur Park” for the band in studio; they say they enjoy it; not long after, Howe calls Webb to tell him the band won’t record it; Howe tells The Association he will quit as their producer if the song becomes a big hit.

To this day, Webb insists he has no hurt feelings.

“There have been rumors down through the years that I have a grudge against those guys and there was bad blood. I never thought about it again,” Webb told me. “You write a song, you play it for somebody, if they record it – fine, it’s great. If they don’t, you throw it in the garbage can and you head on down the road and write something else for somebody else. You don’t look back and certainly you don’t have bad feelings about music. Music is supposed to be fun.”

“I don’t think that I thought that ‘MacArthur Park’ was much more than an experiment. I didn’t have some blinding flash of inspiration,” he added. “The song was completely off my radar. It went to the bottom of the pile. It was a bit of an oddity, a kind of a white elephant. So, I would not have expected 50 years of life from ‘MacArthur Park,’ let alone that I would ever get recorded.”

Richard Harris proved to be the complete opposite. According to Webb’s memoir, after playing Harris the song on piano for the first time, the latter “slapped the top of the piano with the flat of his hand like a gunshot,” extolling: “I’ll have that! Now, Jimmywebb, that’s a song fit for a bloody king!”

***

Lyrically, “MacArthur Park” has weathered a barrage of punches over the years. Despite its allusions to birds, old men playing checkers, “love’s hot-fevered iron,” a striped pair of pants, and, of course, the ubiquitous cake left out in the rain, Webb maintains the song isn’t supposed to be frivolous. One line in his memoir sums it up perfectly: “I wasn’t creating a sucker punch for unwary listeners. I was pouring out my soul on a surreal canvas.”

“That’s what it is, it’s surrealism. It’s an artistic thing,” Webb told me. “For some reason there are just people out there who are personally pissed off about ‘the cake out in the rain.’ Sometimes I think what they’re pissed off about is the bravado of daring to put a seven-minute, 20-second ersatz classical piece on the radio and get away with it. Oh, and have a hit with it … I know where they’re coming from, but I would say why pick on me? I’m defending art and I’m defending the poetic license that we all have to paint our own picture.”

Webb went on to cite examples of other surrealist moments in pop music that are equal parts fantastic and head-scratching. These include Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale” (“I mean pale is white; what is a whiter shade of pale?” Webb asked aloud), The Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever,” and virtually all of Bob Dylan’s work.

I now urge you to go back and take a harder listen to “MacArthur Park.” Pay close attention to its “transformational elements” as Webb describes them (a la Leonard Bernstein). Brought to life by the world-famous Wrecking Crew, Webb’s influences permeate every second of the track – not just Bernstein, but also the aesthetic qualities of the Fab Four, Buddy Holly (the strings of Norman Petty), Ben E. King (“Stand by Me”), and Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound.

Each movement maintains its own resonance, particularly as Harris changes his tone to complement Webb’s lyrical and musical intensity. The thematic backbone of the song is the dissolution of a loving relationship. In Webb’s case, this was real life translated into art. The first movement of “MacArthur Park” (0:00 – 2:32) is somber in its execution as Harris reflects on the relationship through specific imagery. Movement two (2:32 – 4:52) explores the notion of regret as the musical ambiance softens and grows lusher through strings. Movement three (4:53 – 6:27), driven by 3/8 time, embodies pent-up anguish as the mood shifts and grows more intense.

“You listen to that, you can hear the Association,” Webb said. “To me, they were going to tear the wallpaper off the house in the groove.”

This then culminates in the stunning climactic finish (movement four – 6:28 – 7:25) as Harris’ voice soars and all instrumentation merges together in the same forceful vein as “A Day In The Life.” Despite Harris inadvertently reworking “MacArthur” as “MacArthur’s” in his recording, the rest is history.

Webb would win a Grammy in 1969 for Best Arrangement, Instrumental and Vocals for the song. Ten years after Harris became a pop star in the US with his version, Donna Summer took the song all the way to Number One at the height of the disco era. Now, 50 years later, Webb still marvels at the yin-yang life its led: “How would I ever imagine that it would turn into something so controversial and then secondly something that’s like a cultural touchstone for some reason.”

Me, I just think it’s a work of sheer brilliance.

***

Share your feedback and suggestions for future columns with Ira at vinylconfessions84@gmail.com.